METEO 241: Fundamentals of Tropical Forecasting

METEO 241: Fundamentals of Tropical Forecasting mjg8Welcome!

Quick Facts about METEO 241

METEO 241 is one in a series of four online courses in the Certificate of Achievement in Weather Forecasting program. It is offered every Fall (August - September) semester and periodically in the Summer (May - August) semester.

Course Prerequisite(s): METEO 101 (METEO 241 is designed specifically for adult students seeking a Certificate of Achievement in Weather Forecasting. The course will build on the general atmospheric principles covered in METEO 101 in order to draw comparisons between mid-latitude and tropical weather.)

Why learn about tropical forecasting?

When you think of the tropics, you might picture white, sandy beaches and enticing vacation destinations. But, the tropics aren't merely a relaxing paradise. They're also home to some fascinating meteorology! Indeed, some of the most devastating and costly weather disasters on Earth come from the tropics. It's not a coincidence that on the National Centers for Environmental Information's list of billion-dollar weather disasters to affect the United States from 1980 through 2014, the top three came from the tropics!

Furthermore, the tropics comprise a large portion of our planet--up to half of the Earth's surface, depending on the definition of the tropics you use. Thus, the tropical atmosphere and oceans can serve as important drivers for weather all across the globe. Yes, what happens in the tropics doesn't necessarily stay in the tropics! In other words, you simply can't ignore the tropics if you want a complete picture of global weather patterns.

What will you learn in this course?

Your journey through the tropics will begin by meeting the tropics and drawing comparisons and contrasts with the mid-latitudes, and by the end of the course you'll learn all about tropical cyclone development, structure, and hazards to coastal and inland communities. You'll also learn about key forecasting and observational tools that tropical forecasters use to predict tropical weather. METEO 241, however, isn't just a course about tropical cyclones, as the course outline below demonstrates:

Lesson 1: Meet the Tropics (patterns of temperature and pressure in the tropics (and comparisons to the mid-latitudes), naming conventions for tropical cyclones, comparisons between tropical cyclones and mid-latitude cyclones, computer guidance for tropical forecasters, forecasting products from the National Hurricane Center)

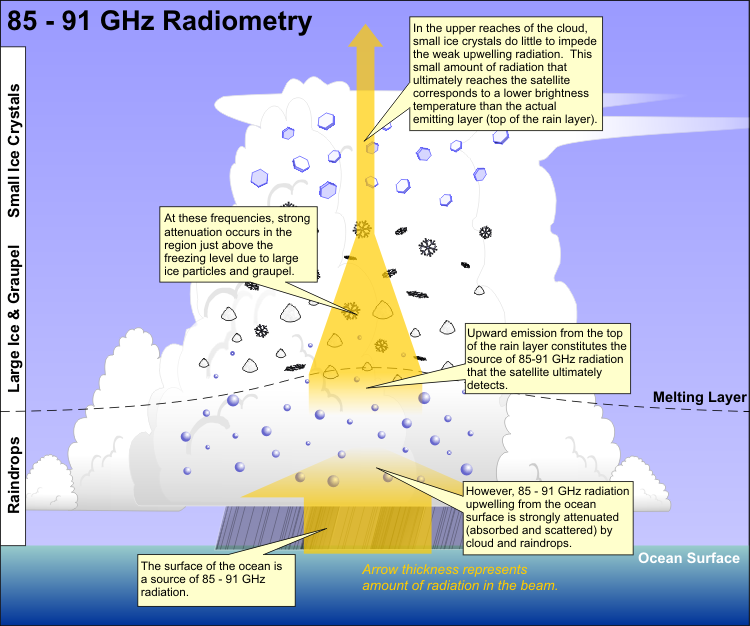

Lesson 2: Remote and In Situ Observations in the Tropics (tropical ocean buoys, Air Force and NOAA Hurricane Hunters, vortex data messages, the Dvorak Technique, cloud-drift winds, assessing precipitation from satellites, the Advanced Microwave Sounding Unit, scatterometry)

Lesson 3: The Tropics from Top to Bottom (the tropical tropopause, potential temperature, mixing ratio, wet-bulb processes, equivalent potential temperature, hot towers and tropical cloud clusters, trade-wind cumulus and subtropical convection, tropical easterly wind / terrain interactions)

Lesson 4: General Circulation (Hadley Cell structure, the Intertropical Convergence Zone, subtropical highs, trade winds and their roles in Earth's angular momentum budget and energy transport, the subtropical jet stream, high-altitude easterly winds in the tropics)

Lesson 5: Monsoons (monsoon definition, likeness to a grandiose sea breeze, monsoon climatology, features that drive the monsoon throughout the troposphere (such as the Somali Low-Level Jet, onset vortex, and Tropical Easterly Jet), monsoon depressions)

Lesson 6: El Niño (air-sea interactions, tropical oceanography, theories for El Niño's onset, the Walker Circulation, local oceanic and atmospheric impacts of El Niño, global teleconnections and seasonal forecasting based on o El Niño and La Niña)

Lesson 7: Tropical Cyclones: Cooking Up a Storm (global tropical-cyclone climatology and its connection to sea-surface temperatures, tropical cyclone heat potential, the role of latitude in tropical cyclone development, low-level vorticity in convective cloud clusters, the role of relative humidity in the middle troposphere, historical and current theories of tropical cyclone development, the role of vertical wind shear, the Statistical Hurricane Intensity Prediction Scheme)

Lesson 8: Tropical Cyclones and the Upper-Air Connection (climatology, origins, and structure of easterly waves, upper-level lows, subtropical cyclones, the Saharan Air Layer)

Lesson 9: Wind Fields in and Around Tropical Cyclones (the dynamics of cyclonic inflow and anticyclonic outflow, structure and forecasting implications of Tropical Upper-Tropospheric Troughs, steering forces for tropical cyclones, the Fujiwhara Effect)

Lesson 10: Structure and Hazards of Tropical Cyclones (eye mesovortices, eyewall dynamics, spiral bands and tornadoes, storm surge, methods of quantifying tropical cyclone destructive potential, inland flooding)

How does this course work?

Much like METEO 101, all course materials are presented online. The course lessons include many animations and interactive tools to provide a tactile, visual component to your learning. Your instructor will assess your progress through online quizzes, lab exercises, and projects, all of which focus on your ability to analyze key observational and forecast information regarding current or past tropical weather events. While deadlines in this course may not occur every week, you should expect to spend 8 to 10 hours per week studying the lesson material and completing assignments to stay on pace. Assignment deadlines generally occur every few weeks.

Lesson 1: Meet the Tropics

Lesson 1: Meet the Tropics mjg8Motivate...

When you think of the tropics, or the word "tropical," you might picture white, sandy beaches, and perhaps sipping on a refreshing, fruity beverage (complete with a tiny umbrella in your glass, of course). Besides being a favorite vacation destination for many people, the tropics are home to some fascinating meteorology. Coming into this course, you should have a good overall grasp of weather in the middle latitudes and how mid-latitude cyclones work. Some of that foundational knowledge will serve as a stepping stone for concepts we'll cover in this course, but we're about to find out that the tropics are quite different than the middle latitudes!

First off, what exactly are "the tropics?" Good question! Actually, folks can't seem to agree on a single definition of the tropics. The definition from the AMS Glossary, for example, is pretty vague! Other definitions are based in geography, and define the tropics as the area between certain latitude lines in each hemisphere. Some definitions actually consider the tropics to be the area between 30-degrees North latitude and 30-degrees South latitude, which is exactly half of the Earth's surface! This large low-latitude region will be our focus throughout this course.

Regardless of what specific definition of the tropics one uses, this large area is characterized by weather that's quite different than that in the middle latitudes. Consider these contrasts between the tropics and the middle latitudes for starters:

- Seasonal swings in temperature across the tropics are typically small compared to the large swings that occur in the middle latitudes from summer to winter. In fact, temperature swings during the year in the tropics can be so small that the seasons are determined more by dramatic changes in clouds and rainfall.

- Wind directions in the tropics tend to be much less variable than they are in the middle latitudes (at many tropical locations, a single particular wind direction tends to dominate).

- Weather systems in the tropics often move from east to west -- exactly the opposite of the typical west-to-east movement of weather systems in the middle latitudes. For example, check out this animation of water vapor images spanning a full year. The movement of weather systems in the tropics clearly goes against the grain of the movement in the middle latitudes.

- Tropical cyclones (the generic name for intense low-pressure systems like hurricanes that form in the tropics) tend to form over warm, tropical seas with weak horizontal temperature gradients. Meanwhile, you've learned that mid-latitude cyclones thrive off of strong horizontal temperature gradients.

Intrigued? The tropics and middle latitudes can be as different as night and day, and we'll explore many of these contrasts in this lesson, and throughout the remainder of the course. Also in this lesson, we'll cover some important basics, such as the map projections commonly used by tropical forecasters, computer guidance, and various forecast products issued by the National Hurricane Center (NHC). If you're eager to learn about tropical cyclones, learning about these basic tools now will help you follow along with developments in tropical weather throughout the semester.

Indeed, if you're ready to "Meet the Tropics," let's get started!

Tropical Temperatures: A "Type B" Personality

Tropical Temperatures: A "Type B" Personality mjg8Prioritize...

By the end of this section, you should be able to describe the difference between the terms baroclinic and barotropic, and associate the proper term with the tropical atmosphere. Furthermore, you should also be able to explain what outgoing longwave radiation (OLR) is, how weather conditions determine its intensity, and how meteorologists use plots of OLR to analyze patterns of clouds and rainfall.

Read...

In order to contrast temperature patterns in the tropics with those in the middle latitudes, allow me to briefly employ an analogy. It might sound a little bizarre, but I'm going to liken temperatures in the tropics and middle latitudes to human personality types. One theory of human personality defines two types -- Type A and Type B. In a nutshell, people with a "Type A personality are "high-strung," obsessed with details and organization, and somewhat rigid. "Type B" personalities on the other hand, are more laid back, "go-with-the-flow" types. They're less stressed out about organization and details.

If I could label the middle latitudes with a human personality, I would probably rate them "Type A". Recall that the middle latitudes mark the region where advancing warm and cold air masses invariably collide. Like a typical "Type A" personality, the middle latitudes seem to be obsessed with organization, dutifully structuring the lower troposphere into narrow zones of relatively large temperature gradients (cold, warm, and stationary fronts). The middle latitudes are constantly trying to manage their temperature gradients in an attempt to be as "organized" as possible.

In contrast, the tropics have a "Type B" personality. As a general rule, horizontal temperature gradients are weak and much more "laid back". To understand why, let's start with the short background video (2:21) below. In case you're wondering, the values of absorbed solar and emitted infrared radiation plotted in the video represent latitudinal (sometimes called "zonal") averages.

Let’s apply the concept of energy budgets to better understand the tropics and how they relate to higher latitudes. This graph is a plot of average absorbed solar and emitted infrared radiation versus latitude, assuming that we treat the earth and atmosphere as one system. The equator is in the middle and the poles are at the sides of the graph. Overall, there’s a net energy gain in the tropics and a net energy loss in the middle and high latitudes. So, let’s see why that’s the case.

The amount of energy per unit area received by the earth depends on the angle at which the sun’s rays strike the earth. Therefore, solar heating is a maximum over the tropics because the intensity of solar radiation is greatest over low latitudes, and over the course of a year, the tropics receive much more incoming radiation than the poles.

On the loss side of the energy ledger, the amount of energy per unit area emitted by the earth depends on surface temperature. The tropics emit a bit more infrared radiation to space because they’re warmer than higher latitudes. But, the amount of infrared radiation emitted in the tropics still pales in comparison to incoming solar radiation.

So, if we construct an energy budget, we’ll see that the tropics are constantly gaining energy because more energy comes in during the course of the year than goes out. Higher latitudes, on the other hand, are constantly losing energy because more energy goes out over the course of the year than comes in.

By itself, this set-up would cause the tropics to get warmer and warmer every year because they always have this surplus of radiation. On the flip side, higher latitudes would get colder and colder every year because they always run a radiation deficit over the course of a year.

But, obviously that doesn’t happen and the reason why is that energy gets transferred throughout the earth system. Energy from the tropics gets transported from low latitudes toward the poles by the atmosphere and ocean to help keep the system balanced, and prevent runaway temperature increases in the tropics and decreases at higher latitudes.

We can confirm the great emission of infrared radiation from the tropics discussed in the video by viewing plots of outgoing long-wave radiation (OLR). For the record, OLR is most intense where surface temperatures are the greatest, such as hot subtropical deserts (the Sahara, for example) during summer. In contrast, OLR is the least intense where it's colder, either because the ground is cold or because deep convection is present. That's because cloud tops in areas of deep convection are high and cold and thus weakly emit long-wave (infrared) radiation.

If we look at the long-term average of OLR across the globe, we can see the general pattern described in the video. The blazing hot Sahara Desert in northern Africa is clearly an area of high OLR values (some of the highest on Earth, denoted by dark purples), while other tropical areas frequently characterized by deep convection (like the Amazon River Basin in northern South America) have lower values. OLR charts have lots of other practical applications for studying trends in cloudiness and rainfall over the tropics (if you're interested in checking out the variety of OLR products available, check out the Earth System Research Laboratory page of OLR plots).

The relatively large losses of infrared energy to space over the tropics only partially offset major-league solar heating, resulting in a broad surplus of energy (shaded in red in the interactive graph above) that varies little with latitude between 30 degrees north and south. This relatively even distribution of surplus energy across the tropics accounts, in part, for the general lack of moderate to strong horizontal temperature gradients in the tropical troposphere.

One other reason for the generally weak temperature gradients at low latitudes is that the water covers approximately 75% of the tropics. That means that the uniform surplus of energy in the tropics gets distributed over large expanses of water, thus further limiting opportunities for strong temperature gradients to form (cold air traveling over relatively warm ocean waters gets rapidly modified).

The figure above represents the long-term average of annual surface air temperatures across the globe. I point out that there are indeed temperature gradients between tropical land masses and surrounding oceans, but the overall pattern of temperature gradients in the tropics is weak compared to those at higher latitudes.

Now I readily admit that any annual average in temperature tends to "wash out" strong signals of gradients in winter, so perhaps a look at temperatures for a single day would more effectively drive home my point. Check out daily global surface temperatures for January 23, 2013, when sharp temperature gradients existed over eastern North America, for example, on the fringe of a continental Arctic air mass. Now, compare them to the flabby gradients over the tropics. No contest, wouldn't you agree? Notice that there are some sharper gradients along the outer fringes of the tropics near 30 degrees north. These larger gradients near 30 degrees are not unusual, given that Arctic air masses drive farther south in winter (occasionally into the fringes of the tropics). In the heart of the tropics, however, gradients are weak by almost any standard.

The lack of large temperature gradients does not stop at the surface, of course. At 500 mb, for example, the lack of strong temperature gradients over the tropics is striking compared to the middle latitudes (check out the annual mean 500-mb temperatures across the globe). So, with regard to temperature gradients, the tropical troposphere has a completely different personality than the middle latitudes.

I hope the analogy to personality types helps you to understand the different nature of temperature patterns in the tropics and middle latitudes, but now it's time to get a bit more formal. How do we formally describe these different "personalities" of the middle latitudes and the tropics? Meteorologists formally refer to the "Type A" middle latitudes as baroclinic and the "Type B" tropics as barotropic. In the broadest terms, a baroclinic atmosphere is one where horizontal temperature gradients prevail. The middle latitudes, for example, are highly baroclinic during winter, when large horizontal temperature gradients often set the stage for strong temperature advection. A barotropic atmosphere, on the other hand, is one in which temperature advection is pathetically weak. In the presence of wind, that means that horizontal temperature gradients must all but vanish. For all practical purposes, the tropics are bereft of horizontal temperature gradients, so "barotropic" best describes the tropical atmosphere.

Recall from the video discussing absorbed solar and emitted infrared radiation versus latitude that, while the tropics run a surplus in energy, the middle and polar latitudes run a deficit. Thus, to balance the ledger of the earth-atmosphere system, it is pretty obvious that there must be a transfer of heat energy poleward from the tropics. This transfer is accomplished by the meridional transport of heat energy by the atmosphere and the oceans. You may already be familiar with some mechanisms for this transport, such as the Gulf Stream (an ocean current that conveys heat energy northward from low latitudes).

As far as atmospheric transport of heat energy goes, there are several mechanisms working to export heat energy out of the tropics, which we'll explore in later lessons. For now, though, recall that large mid-latitude cyclones are very effective at transporting warm air northward and cold air southward with their broad circulations. Given the large north-south temperature gradients that prevail in the middle latitudes during the cold season, the large impacts on regional temperatures from strong advection qualify mid-latitude cyclones as "big business" in the world of heat transport. Is the same true for tropical cyclones? Not really. Tropical cyclones transport some heat energy and moisture from the tropics to higher latitudes, but their overall contribution pales in comparison to other transport mechanisms. If you're interested, check out the "Explore Further" section below for more on this topic and another peculiarity that arises from the barotropic nature of the tropics. Otherwise, get ready to explore another aspect of the "Type B" behavior of the tropics on the next page.

Explore Further...

Tropical Cyclones and Meridional Heat Transport

Although hurricanes (intense low-pressure systems that develop over warm tropical seas and attain maximum sustained winds of 64 knots (74 mph) or more) usually grab top billing on the evening news, they are "small-potatoes" when it comes to exporting tropical heat energy (and moisture). Granted, these "heat engines" sometimes venture far northward (check out animation of visible and infrared satellite images of Hurricane Irene between August 19 and August 29, 2011, for example), but even fairly large hurricanes like Irene are small in the grand scheme of weather systems. For another perspective on Irene's size, check out this full-disk infrared satellite image from GOES-East taken at 15Z on August 26, 2011. Irene (which again, was large by hurricane standards) doesn't look very big, does it? Not surprisingly, then, in the final analysis, the storm didn't transport much heat energy or moisture poleward. Also keep in mind that hurricanes form during the warm season, so the impact of their heat energy on the already warm middle latitudes is limited.

Now, for comparison, check out this sequence of GFS forecasts of 850-mb temperature, wind, and surface highs and lows from the 12Z run on February 22, 2019. Using 850-mb temperatures to track warm and cold air, watch how the temperature field evolves as a low-pressure system develops in the central Plains and then deepens substantially on its trek through the Great Lakes in to eastern Canada. Clearly, colder air plunges southward on the western side of the developing low thanks to cold advection (note that the 0 degree Celsius isotherm dips to the Georgia / Tennessee border by the end of the loop). Meanwhile, east of the low, warmer air surges northward thanks to warm advection (the 0 degree Celsius isotherm advances as far north as Quebec). Without reservation, this mid-latitude low is a big-business meridional transporter of heat energy.

Seasonal Variations in Tropical Temperatures

Unlike the middle latitudes, there are places in the tropics that have two annual peaks in temperature during the warm season (instead of one). For example, compare the plot of the annual variation in average temperatures at St. Louis, Missouri, with a similar plot at Bhopal, India. Note the single peak in average temperatures at St. Louis around the middle of July. In contrast, the trace of average temperature at Bhopal shows a much smaller annual variation, and shows two peaks -- one in early May and another just before the start of October.

The relatively small annual variation at Bhopal occurs in large part because of the relatively direct solar radiation that occurs year-round at Bophal's latitude (around 23 degrees North). Seasonal changes in clouds and rainfall, however, make substantial differences in Bhopal's temperatures from one season to another. The "dip" in temperatures that occurs at Bhopal from May through September, for example, coincides with the rainy season in Bhopal (advance to the second slide to view average monthly precipitation at Bhopal). We'll explore the reasons behind these seasonal changes in clouds and rainfall in a later lesson.

Pressure in the Tropics: More "Type-B" Behavior

Pressure in the Tropics: More "Type-B" Behavior ksc17Prioritize...

Upon completion of this section, you should be able to compare typical pressure gradients in the tropics with those in the middle latitudes, and be able to interpret frequency of wind directions and speeds from wind rose diagrams.

Read...

Just as the tropics display a "Type B" personality with respect to temperatures, they generally maintain that same personality when it comes to pressure. In the tropics, pressure gradients tend to be much more relaxed than they do in the "Type-A" middle latitudes (resuming our analogy from the previous page). If you look at the surface analysis over the northern Atlantic Basin at 06Z on September 8, 2003 below, you should note that the middle latitudes (toward the top of the image) have much tighter pressure gradients than low latitudes. The exception to the rule is tropical cyclones, of course. The tightly-packed isobars around Hurricane Isabel indicate a strong pressure gradient, as do those around Hurricane Fabian (which was on the doorstep of the middle latitudes).

By the way, the map projection here is polar stereographic

Text description of the September 8, 2003 06Z image.

The 06Z surface analysis over the North Atlantic Basin from 06Z on September 8, 2003 shows generally weak pressure gradients over the tropics, except for Hurricane Isabel

The image is a detailed weather map, displaying the North Atlantic region, including parts of North America, Europe, and Africa. It features numerous isobars, which are black contour lines representing areas of equal atmospheric pressure, and weather fronts, indicated with varying line styles and symbols. High and low-pressure systems are marked by "H" and "L" respectively, scattered throughout the map. Distinctive systems include several hurricanes represented by circular isobars with progressively lower pressure toward the center, notably Hurricane Fabian and Hurricane Isabel. The map is covered with meteorological symbols and numerical codes that indicate specific conditions like wind speed and direction. Numerous regions with varying air pressures are marked, with discernible shapes and troughs. The map also contains textual data enclosed in boxes related to storm tracking, such as coordinates, dates, and maximum wind speeds.

So it is pretty apparent that the relatively small (large) temperature gradients over the tropics (middle latitudes) go hand in hand with relatively small (large) pressure gradients. At this point, the only flies in the ointment seem to be tropical cyclones. Indeed, tropical cyclones do something that is unheard of in the middle latitudes: they form in an environment bereft of large temperature gradients yet somehow develop very large pressure gradients around their centers.

The overwhelming message, however, is that pressure gradients are typically weak across the tropics. That also means that changes in surface pressure with time at any given location are usually puny compared to the larger increases and decreases that regularly accompany the approach and passage of mid-latitude high- and low-pressure systems. In the equable tropics, pressure patterns can persist for very long periods (weeks and even months). Yet, almost mysteriously, there is a regular daily rhythm of changes in surface pressure that meteorologists detect in the tropics. If you're intrigued, check out the "Explore Further" section at the end of the page.

For a broader view of pressures across the tropics and how they compare to those in the middle latitudes, check out the chart of average sea-level pressures at 00Z on February 12, 1998 below. At the time, there were intense northern hemispheric low-pressure systems over the Gulf of Alaska, the Great Lakes, the middle Atlantic Ocean, northern Russia and the east coast of Asia (splotches of blues and purples on the map). Meanwhile, robust high-pressure systems (bigger blobs of greens, yellows, oranges and reds) were interspersed between the intense lows.

In the tropics, on the other hand, pressure patterns are much more relaxed and much more equable than the middle latitudes. In other words, prominent centers of high and low barometric pressure are more difficult to find, especially equator-ward of latitudes 30 degrees north and south, which mark the very outer fringes of the tropics. The most notable exception to the generally more relaxed pattern of pressure in the tropics on February 12, 1998, was a tropical cyclone, not surprisingly. The spot of relatively low pressure (blue splotch) just to the east of Madagascar in the southwest Indian Ocean is the signature of Tropical Cyclone Ancelle, which reigned over the southwest Indian Ocean from February 5 to February 13, 1998 (during the southern hemisphere's summer).

The height patterns on constant pressure surfaces over the tropics are similarly relaxed. Consistent with the general lack of temperature gradients at 500 mb over the tropics, note the absence of strong gradients between 30 degrees latitude (north and south) on this chart of long-term mean 500-mb heights. Height contours on the other mandatory pressure levels in the tropical troposphere show a similarly relaxed pattern.

Since the pressure gradient force is a primary driver of wind speed, you might think that the winds are almost always weak in the tropics (outside of tropical cyclones, that is), with the weak pressure gradients at the surface and aloft. But, that's far from the truth! To help you visualize the fact that many places in the tropics are quite breezy, despite weak surface pressure gradients, I'm going to introduce a new type of plot -- the wind rose. Wind roses display the observed frequency of wind directions (and sometimes speeds) at a particular location. On the left below is a histogram displaying frequencies of observed wind speeds (in meters per second) at an ocean buoy moored at 8 degrees South, 95 degrees West during the year 2002. On the right is the corresponding wind rose for the buoy, which shows the frequency of observed wind directions during the same year.

From these two images, we can quickly get two important messages. First, wind speeds at the buoy were between five and nine meters per second (roughly 10 to 20 mph) the vast majority of the time, which hardly constitutes "weak" winds. Second, the direction from which the wind blew during the year was remarkably consistent. To get your bearings with the wind rose, note that each concentric ring represents a ten-percentage point increase in the relative frequency of the observed wind direction. Thus, the daily mean wind direction of 130 degrees (from the southeast) occurred on nearly 45% of the days, and the daily mean wind direction of 140 degrees occurred on about 28% of the days! The wind rose clearly demonstrates that winds retained their overall southeasterly direction for almost the entire year (and didn't deviate much from 130 degrees). Small variations in wind direction and breezy conditions are fairly typical in tropical locations because of the famous belt of "trade winds," which we'll cover formally in a later lesson.

Many wind roses that you'll encounter also include wind-speed data right on the wind rose plot. For example, check out this wind rose plot for the month of March at Grand Rapids, Michigan. At first glance, it's easy to see that it looks much different than the wind rose from the tropical ocean buoy shown above. Wind directions are much more variable during the month, which is more common in the middle latitudes thanks to the parade of high- and low-pressure systems that march around the globe. On this wind rose, each concentric ring represents a two-percent increase in the relative frequency of the observed wind direction, so the most common wind direction at Grand Rapids during March (from 90 degrees -- due east) occurs a little less than 10% of the time.

The various colors along each "spoke" represent wind speed ranges according to the color key at the bottom of the image. So, along the 90-degree "spoke," winds between 1.80 meters per second and 3.34 meters per second (roughly 3.5 - 6.5 knots) marked by the yellow shaded area occurred approximately 2% of the time. Winds between 3.34 meters per second and 5.40 meters per second (roughly 6.5 knots - 10.5 knots) marked by the red shaded area occurred about 3.5% of the time (5.5% - 2%). Winds between 5.40 meters per second and 8.49 meters per second (roughly 10.5 - 16.5 knots) marked by the blue shaded area occurred about 3.5% of the time (9% - 3.5% - 2%), and so on. Along any given spoke, the individual percentages for each range of wind speeds should sum to the total percentage associated with the entire spoke.

I strongly recommend taking some time to practice extracting information from wind roses (you can start with the "Key Skill" section below). Wind roses can provide lots of practical information. For example, consulting meteorologists use wind roses when the work on the design of airports (runways should be built to avoid strong crosswinds), and skilled forecasters regularly use wind roses when studying the climatology of a particular location. After you're comfortable with interpreting wind roses (and check out the "Explore Further" section, if you wish), you'll be ready to examine another difference between the tropics and the middle latitudes -- the structure of mid-latitude cyclones versus the structure of tropical cyclones.

Key Skill...

You'll need to interpret wind roses not only in this course, but future courses, so it's a good idea to spend a little time making sure you're comfortable with gathering basic information from them. Consider the March wind rose plot from Grand Rapids, Michigan and answer the following questions. If you do not understand the answers to these questions, be sure to review the guidelines for interpreting wind roses above and / or ask your instructor for clarification.

Question #1

During the month of March at Grand Rapids, which wind direction is observed the least frequently on average? What percentage of the time is this wind direction observed?

Answer: North-northeasterly winds are observed least frequently at Grand Rapids during March. Winds from the north-northeast are only observed slightly less than 3% of the time.

Question #2

Which wind direction most frequently produces wind speeds greater than 11.06 meters per second (roughly 21.5 knots)?

Answer: West-southwesterly winds most frequently produce speeds greater than 21.5 knots (almost 1% of the time), followed closely by southwesterly winds. The light blue shaded area corresponding to these speeds is largest along the west-southwesterly and southwesterly spokes.

Question #3

What percentage of the time do winds blow from the west-southwest between 3.34 meters per second and 8.49 meters per second (roughly 6.5 - 16.5 knots)?

Answer: Winds blow from the west-southwest between 6.5 knots and 16.5 knots slightly more than 5% of the time. We have to add the percentages that correspond to the red shading (slightly less than 3%) and blue shading (more than 2%).

Explore Further...

As you learned on this page, pressure gradients in the tropics tend to be very relaxed, and changes in surface pressure with time at any given location are usually puny compared to the larger variations that regularly accompany the approach and passage of high and low-pressure in the middle latitudes. In the equable tropics, pressure patterns can persist for very long periods (weeks and even months). Yet, almost mysteriously, there is a regular daily rhythm of changes in surface pressure that meteorologists detect in the tropics.

To see what I mean, focus your attention on the time-trace of barometric pressure at Nauru, a tropical island in the western Pacific just a tad south of the equator. For the record, the trace in barometric pressure spans from midnight on April 16, 2003, to midnight on April 25, 2003. Although the fluctuations in pressure are relatively small in the grand scheme of weather (only a few millibars), there is an undeniable rhythm to the ebb and flow of the barometer. Indeed, much like the tides of the oceans, there are two high and two low "tides" in pressure that occur each day. In other words, there is a persistent oscillation in barometric pressure at Nauru that has a period of half a day (one high tide and one low tide in 12 hours). To better see this "semi-diurnal" oscillation in pressure at Nauru, check out this annotated version of the barograph trace. This semi-diurnal oscillation in barometric pressure is a staple of the tropics.

As it turns out, the amplitude of the pressure tides is largest in the tropics, where pressure variations generated by passing weather systems are routinely small. So, it's no wonder that these pressure tides stand out on barograph traces. In contrast, the amplitude of pressure tides is much smaller over the middle latitudes (the amplitude of the semi-diurnal pressure tide falls off dramatically with increasing latitude), so they are usually dwarfed by much larger pressure variations produced by passing weather systems (making them difficult or impossible to detect on barograph traces).

For the record, the greatest amplitude of the semi-diurnal pressure tide, which is a approximately one or two millibars, occurs at the equator. So, why do they exist? In a nutshell, the atmosphere absorbs only about 10 percent of the incoming solar energy. Ozone in the stratosphere accounts for a large fraction of the atmosphere's absorption, while, to a lesser degree, tropospheric water vapor accounts for most of the rest of the atmosphere's absorption of solar energy. At any rate, the resulting warming of the atmosphere after sunrise (and cooling on the other side of the earth) creates sufficient changes in air density that internal gravity waves form and propagate both vertically and horizontally. As these density-driven waves reach the earth's surface, they induce noticeable changes in pressure over the equable tropics. At higher latitudes, these gravity waves become "vertically trapped" and their affects on surface pressure become increasingly unimportant (the proof of the vertical trapping of internal gravity waves at higher latitudes involves very sophisticated mathematics and is beyond the scope of this course).

Tropical Cyclones: What's in a Name?

Tropical Cyclones: What's in a Name? ksc17Prioritize...

Upon completion of this section, you should be able to identify the basins across the globe that typically produce tropical cyclones and interpret the meaning of tropical cyclone classifications (such as tropical depression, tropical storm, etc.). Although you will not be specifically tested on the various naming conventions used in basins around the world, you should leave this page with a basic idea of the various naming schemes because it will give you context for the various case studies that we will discuss throughout the course, and help you track tropical cyclones globally.

Read...

Up to this point, you've seen the generic phrase "tropical cyclone" used to describe the low-pressure systems that form over warm tropical seas. However, as you're about to find out, naming and classifying tropical cyclones is somewhat complicated. Before we get into how tropical cyclones are named, let's look at the areas where tropical cyclones tend to form. Do they form just anywhere in the tropics? Not really. As you can see from the image below, the breeding grounds and regions where tropical cyclones typically track can be boiled down to seven areas:

- Atlantic Basin (the northern Atlantic Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean Sea)

- Northeast Pacific Basin (from Mexico to the International Dateline)

- Northwest Pacific Basin (from the International Dateline to Asia, including the South China Sea)

- North Indian Basin (includes the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea)

- Southwest Indian Basin (from Africa to about 100 degrees east longitude)

- Southeast Indian/Australian Basin (100 degrees east longitude to 142 degrees east longitude)

- Australian/Southwest Pacific Basin (142 degrees longitude to about 120 degrees west longitude

Of these seven areas, the Northwest Pacific and Northeast Pacific basins tend to be the busiest, as this frequency plot for tropical cyclones suggests. It shows the average number of occurrences (from 1972 to 2001) that the center of a tropical cyclone occupied an area with dimensions of one degree latitude by one degree longitude (based on each storm's best track). The dark red color indicates the highest average of such occurrences and thus marks the core of these breeding basins for tropical cyclones. Meanwhile, some areas in the tropics are nearly entirely free of tropical cyclones. While tropical cyclones can form outside of the seven areas listed above, it happens relatively infrequently. For example, the southern Atlantic Ocean (south of the equator) is rarely home to tropical cyclones.

With tropical cyclones in any basin possibly impacting multiple countries, how do forecasters keep tabs on all of them? The World Meteorology Organization created a branch called the Tropical Cyclone Programme (TCP) to ensure that all countries bordering and within each basin are adequately prepared for the threat posed by tropical cyclones. To accomplish this goal, the TCP's primary responsibility is to establish a nationally and regionally coordinated network of forecasting centers. To define areas of responsibility, they partitioned the tropical-cyclone basins and assigned Regional Climate Centers (RCCs), which issue the official forecasts and advisories for their respective basins (see figure below). If you wish, you can check out the WMO Web Page that lists the links to the Tropical Cyclone RCCs where you can access all the current RCC advisories.

Although each RCC is responsible for issuing the official forecasts and advisories for their jurisdiction, there can be multiple cities which issue warnings for various countries under the umbrella of a single RCC. For example, the official advisories and forecasts for the Atlantic Basin come from: the National Hurricane Center in Miami, but the Canadian Hurricane Centre in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia issues warnings when tropical cyclones threaten Canada, using the National Hurricane Center's products as their basis. Keep in mind that Atlantic hurricanes and tropical storms moving northward along the East Coast can pose a significant threat to the Canadian Maritimes (the provinces of New Foundland, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island).

In addition to the Regional Specialized Meteorological Centers and Tropical Cyclone Warning Centers on the map above, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) is an additional warning center and serves as a joint effort between the United States Navy and Air Force. JTWC was founded in 1959 in Guam, but has since moved to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. While JTWC does not issue official public forecasts, they keep tabs on tropical cyclones globally for U.S. Department of Defense interests.

Now that we know who's keeping track of tropical cyclones around the globe, we can delve into how they keep track of them. That's where things can get a bit complicated because standards differ across the globe. For starters, forecasters often have their eyes on clusters of showers and thunderstorms across the tropics (often called "tropical disturbances"). Tropical disturbances do not have closed circulations and are not formally tropical cyclones; however, by convention in the U.S., tropical disturbances that have the potential to develop into tropical cyclones are dubbed "invests." Each invest is tagged with a number from 90-99 along with a capital letter, which corresponds to the tropical basin where it's located (see the table below for the letters that correspond to each basin). Forecasters start with the number 90 and sequentially progress to 99, and then start over again at 90. So, for example, Invest 99L in the Atlantic Basin would be followed by Invest 90L, and so on.

If the tropical disturbance with organized convection develops a closed cyclonic circulation in its surface wind field, it becomes a tropical depression as long as its maximum sustained wind speeds are less than 34 knots (39 miles per hour). Note that different definitions of "sustained" (as described in the link) can lead to different storm classifications in different basins. Tropical depressions are formally considered tropical cyclones, and at this point The Joint Typhoon Warning Center, Central Pacific Hurricane Center, and the National Hurricane Center routinely assign a new number to go along with the letter referring to the basin of origin. For each season in each basin, the digits start at "01" and then increase by one for each successive depression that forms. Since the capital letter refers to the basin of origin, the letters are not changed if tropical cyclones cross 140 or 180 degrees longitude. I should note, however, that depressions in the Atlantic Basin are an exception. When a depression is classified in the Atlantic, the National Hurricane Center simply refers to it by its number ("One", "Two", etc.) and the letter "L" gets dropped from the designation.

| Letter | Basin |

|---|---|

| L | North Atlantic |

| W | Western North Pacific (west of 180°) |

| C | Central North Pacific (140 to 180°W) |

| E | Eastern North Pacific (east of 140°W) |

| A | Arabian Sea |

| B | Bay of Bengal |

| S | South Indian Ocean (west of 135°E) |

| P | South Pacific Ocean (east of 135°E) |

Once a tropical cyclone reaches sustained wind speeds of at least 34 knots (39 miles per hour), it becomes a tropical storm and receives a name (more on the naming of tropical cyclones in a bit). Tropical cyclones retain their tropical storm status as long as their maximum sustained winds remain between 34 knots and 63 knots. Once a tropical cyclone reaches maximum sustained winds of at least 64 knots (74 miles per hour), it loses its "tropical storm" label, and earns the classification of hurricane, typhoon, severe cyclonic storm, tropical cyclone or severe tropical cyclone, depending on the basin in which the storm is located (see the table below for what words are used in each basin. At times, I may generically refer to "hurricanes" in the text, but keep in mind that such references also include strong tropical cyclones that go by various labels in basins around the world.

| Word | Basin(s) |

|---|---|

| Hurricane | Atlantic, Northeast Pacific, South Pacific (east of 160ºE) |

| Typhoon | Northwest Pacific |

| Tropical Cyclone | Southwest Indian (west of 90ºE) |

| Severe Tropical Cyclone | Southeast Indian (east of 90ºE) |

| Severe Cyclonic Storm | North Indian |

Of course, all "strong" tropical cyclones (hurricanes, typhoons, etc.) are not created equal. Some are much more intense than others. In the Atlantic and Northeast Pacific basins, forecasters use the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale to further classify a given hurricane. Hurricanes classified as "Cat 3", "Cat 4" or "Cat 5" (all hurricanes with maximum sustained winds of at least 96 knots, or 111 mph) qualify as major hurricanes. Although major hurricanes make-up only 21% of the hurricanes that hit the United States, these fierce storms account for over 83% of all the damage from landfalling hurricanes. For the record, Australian forecasters, rank tropical cyclones a bit differently.

Other basins also have different descriptors for extremely intense tropical cyclones. In the Northwest Pacific Basin, for example, the particularly descriptive classification of "super typhoon" is used once a typhoon's maximum sustained wind speed reaches at least 130 knots (more than twice the minimum typhoon wind speed). For some interesting tidbits on some memorable super typhoons, check out the Explore Further section below. In the North Indian Ocean, meanwhile, severe tropical cyclones that attain maximum sustained winds of at least 130 knots graduate to super cyclonic storm.

The Name Game

There's a checkerboard history behind the naming of tropical cyclones in the various basins around the world. If you're interested in the history of naming tropical cyclones, I encourage you to check out the corresponding section within Explore Further below. The reason why tropical cyclones get named, however, is pretty straightforward. The practice of naming tropical cyclones ensures clear, unambiguous communication between forecasters and the general public when forecasts, watches, and warnings are issued. At any given time across the globe (or even within a single tropical basin) there can be multiple tropical cyclones present at any one time. For example, the satellite image from September 2, 2008 (below) shows a whopping four named storms present in the Atlantic Basin!

Without the practice of naming tropical storms, deciphering forecasts with four active storms in the basin could have been a real mess -- sifting through coordinates or other technical descriptions of a storm's location. In the end, using names is much simpler for the general public, so let's get to the (not so simple) business of how storms are named. In the Atlantic and eastern Pacific, the World Meteorological Organization and National Weather Service (NWS) have used lists of alternating male and female names in alphabetical order to christen storms since 1979 (check out the lists currently in use if you wish).

I should point out that any year that the alphabetical list of male and female names is not long enough to accommodate all the named storms in a season, the National Hurricane Center turns to a supplemental list of names; however, prior to 2021, the standard was to use letters of the Greek Alphabet (Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, etc.) to name storms once the original list of names had been exhausted. Use of the Greek Alphabet to name storms only occurred twice (2005 and 2020).

For Central Pacific storms, the Central Pacific Hurricane Center uses its own list of names of Hawaiian origin. Because not many tropical cyclones form in the Central Pacific, they don't restart the list from the beginning each year, and instead they just keep using the same list until all the names have been used. When they reach the end of one list, they simply begin with the first name on the next list.

Meanwhile, in the northwest Pacific Basin, since the year 2000, the World Meteorological Organization has used names which are, for the most part, not male or female names. Instead, most names on the list refer to flowers, animals, birds, trees, or even foods, etc. Others are simply descriptive adjectives. Each name on the list is contributed by a participating nation within the basin. The names are not used in alphabetical order like in the Atlantic and eastern Pacific, however. Instead, the contributing nations are listed in alphabetical order and this ranking determines the order that the names are assigned.

It's important to note, however, that the established lists from the World Meteorological Organization are not universally used for storms in the northwest Pacific. The Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration (PAGASA) assigns Filipino words as storm names when storms threaten the Philippines so that locals can easily remember them and communicate about the storm. For example, in November 2013 Super Typhoon Haiyan made landfall in the Philippines as one of the strongest tropical cyclones on record at the time of landfall. But, in the Philippines, Haiyan (which is from the Chinese for "petrel" -- a type of seabird) was known as "Yolanda." So, be aware that you may come across two names for some storms in the northwest Pacific Basin.

Finally, in the North Indian Ocean, tropical cyclones weren't named from a traditional list until 2004. Prior to that year, conventions for identifying storms and keeping historical records were somewhat awkward (more in Explore Further). With regard to name selection, eight countries belonging to the WMO Tropical Cyclone panel for the North Indian basin contributed eight names each, which were tabulated into eight columns. In each column, one name from each country appeared, with the names listed in the order determined by the alphabetized contributing nations (the same convention as in the Northwest Pacific basin). You can see the lists of names for tropical cyclones in the North Indian Ocean and all other tropical basins (including basins not covered in-depth here) on the World Meteorological Organization's page of tropical cyclone names.

An average of approximately 80 strong tropical cyclones form each year worldwide -- a small number compared to the hundreds and hundreds of cyclones that parade across the middle and high latitudes each year. Yet, the attention that meteorologists focus on tropical cyclones sometimes seems disproportionately great. That's because strong tropical cyclones can cause staggering losses of life and property. Next up, we'll compare tropical cyclones with mid-latitude cyclones. Not surprisingly, there's a world of difference between them!

Explore Further...

Some Memorable Super Typhoons

The northwest Pacific basin is home to some of the most impressive tropical cyclones in the entire world, and the term used to classify extremely strong tropical cyclones in the basin -- "super typhoon" is very appropriate. In November 2013, Super Typhoon Haiyan made landfall in the Philippines with estimated maximum sustained winds of 195 miles per hour and an estimated central pressure of 895 millibars. Even though Haiyan may have been the most intense tropical cyclone on record at landfall, it's not the most intense tropical cyclone in recorded history (in terms of lowest sea-level pressures, anyway). That honor goes to Super Typhoon Tip (1979). The lowest sea-level pressure ever recorded on Earth occurred in Super Typhoon Tip -- 870 millibars. Tip spent 48 consecutive hours as a super typhoon, which was a record at the time. That record, however, has since been smashed by two super typhoons that occurred simultaneously!

In 1997, there were two super typhoons in the northwest Pacific basin at the same time, Ivan and Joan (see image below). Ivan's maximum sustained winds reached approximately 160 miles per hour on October 18, 1997, and Joan's top winds approached 180 miles per hour (also on the 18th). Both Joan and Ivan smashed Tip's endurance record as a super typhoon, with Joan lasting more than 100 consecutive hours as a super typhoon and Ivan completing more than 60 straight hours as a super typhoon. In modern times, there have never been two simultaneous super typhoons with such great, sustained intensity.

For History Buffs

Above, I summarized the current methods for naming tropical cyclones in most of the major tropical basins, but conventions have changed over the years. Indeed, each basin has its own unique history of naming tropical cyclones. In the Atlantic, the earliest practice of naming Atlantic hurricanes goes back a few hundred years to the West Indies. Indeed, islanders named hurricanes after saints (when hurricanes arrived on a saint's day, locals christened the storm with the name of that saint). For example, fierce Hurricane Santa Ana struck Puerto Rico on July 26, 1825, and Hurricane San Felipe (the first) and Hurricane San Felipe (the second) hit Puerto Rico on September 13, 1876 and September 13, 1928, respectively.

During World War II, US Army Air Corps forecasters informally named Pacific storms after their girlfriends or wives (who probably wouldn't have been happy if they had known). That apparently started the ball rolling in the United States. From 1950 to 1952, meteorologists named tropical cyclones in the North Atlantic Ocean according to the phonetic alphabet (Able, Baker, Charlie, etc.). Then, in 1953, the U.S. Weather Bureau switched the list to female names. In 1979, the World Meteorological Organization and the National Weather Service (NWS) amended their lists to also include male names.

Elsewhere around the globe, an Australian forecaster named Clement Wragge began to name tropical cyclones after politicians he disliked just before the start of the nineteenth century. Forecasters in the Australian and South Pacific regions (east of longitude 90 degrees East, and south of the equator) formally started to christen tropical storms with female names in 1964. They beat the United States to the punch and began to use both male and female names in the mid 1970's.

Prior to the current convention in the northwest Pacific, JTWC forecasters started to use female names for tropical cyclones in 1945. In tandem with the 1979 change in the United States, forecasters amended their lists to include male names, but they abandoned that practice on January 1, 2000 when they switched to the current convention of using words that are typically not male or female names.

Finally, above I mentioned that conventions for naming storms and keeping historical records were somewhat awkward in the North Indian basin before 2004. Before storms were named from a list, in real-time, forecasters simply used the two-digit / letter label that the cyclone received once it attained tropical-depression strength (for example, "Tropical Cyclone 02A" for the second tropical cyclone of the year in the Arabian Sea). Keeping historical records got a bit complicated because forecasters used an identification code composed of an Arabian Sea / Bay of Bengal indicator, the last two digits of the year and a two-digit number that designated the order of occurrence of the storm during that year. For example, a storm with the coded ID, BOB 9903, was the third tropical cyclone of 1999, and it formed in the Bay of Bengal (BOB). Records now include the name of the storm, but most storm reports you'll see from this basin will reflect past and present conventions. For example, the very first storm named from a list in the basin was "Onil" on October 1, 2004. It was frequently referred to in statements as "Tropical Cyclone Onil (03A)".

Comparing Tropical and Mid-Latitude Cyclones

Comparing Tropical and Mid-Latitude Cyclones mjg8Prioritize...

Upon completing this page, you should be able to compare and contrast the basic structure and evolution of tropical and mid-latitude cyclones. Specifically, you should be able to discuss differences in vertical motion over the centers of mid-latitude cyclones and hurricanes, and the implications of these differences in terms of temperatures, relative humidity, and surface pressure. You should also be be able to define key parts of a hurricane's structure (such as eye, eyewall, spiral bands, and secondary circulation). Finally, you should leave this page being able to summarize the basic feedback process that causes tropical cyclones to intensify.

Read...

With the great potential for loss of life and property posed by tropical cyclones, they certainly garner great attention from weather forecasters and the public at large. But, why do powerful tropical cyclones more frequently steal national and international headlines, while mid-latitude cyclones rarely do? The first reason is likely that mid-latitude cyclones are more numerous. Hundreds of them trek across the globe each year. Meanwhile, only about 80 tropical cyclones develop each year.

Secondly, a tropical cyclone can attain a much greater intensity in terms of both sea-level pressure and wind speed (some even call hurricanes the "kings" of all low-pressure systems). For example, the most intense tropical cyclones can have sea-level pressures below 900 mb. Typhoon Tip (1979) had the all-time lowest at 870 mb, but other storms such as Hurricane Wilma (2005) and Super Typhoon Haiyan (2013) have had central pressures below 900 mb. On the other hand, the sea-level pressure at the center of a mid-latitude cyclone rarely drops below 950 mb. For example, the Superstorm of 1993 (aka the "Storm of the Century"), had a central pressure of 963 mb at its peak.

With these observations in mind, a natural question might be, "Why do strong tropical cyclones often attain sea-level pressures that are notably lower than those associated with mid-latitude cyclones?" While both types of cyclones are low-pressure systems, the answer to that question can found by examining the differences in structure and strengthening mechanisms characteristic of each type of low-pressure system.

For starters, recall that mid-latitude cyclones undergo the process of self-development. This process requires the cyclone to develop in a region of strong horizontal temperature gradients (a baroclinic zone, or front) and under a region of strong upper-level divergence. In short, divergence downwind of a 500-mb shortwave trough reduces the weight of air columns, forming an area of low pressure at the surface, around which winds rotate counterclockwise (in the Northern Hemisphere). Decreasing surface pressures result in a stronger pressure gradient force, which causes faster winds. As winds around the cyclone increase, cold-air advection southwest of the low increases, causing 500-mb heights to fall and the 500-mb trough and vorticity maximum to strengthen. In turn, upper-air divergence increases over the center of the low, causing surface pressures to further decrease and surface winds to increase further. This positive feedback loop continues uninterrupted until the late stages of occlusion, when the low moves back into the cold air (away from the baroclinic zone) and upper-level divergence over the low weakens (the low starts to "fill" -- surface pressure rises).

In a nutshell, the magnitude of the divergence aloft (which is greater than the magnitude of the convergence at lower altitudes) drives the intensity of the mid-latitude cyclone. Also note, however, that the divergence aloft along with low-level convergence drives upward motion over the center of the low. You'll occasionally read or hear explanations that suggest that rising causes lower surface pressures, but that's just not true. In fact, just the opposite is true. Rising air actually works against the overall reduction in surface pressure.

Recall that rising air cools via expansion, and once clouds and precipitation develop, can also yield evaporational cooling (assuming the atmosphere is not already at saturation). In turn, cooling by forced ascent increases the mean density in the column of air that extends from the ground to the tropopause (low-level convergence and upper-level divergence are still at work). Assuming a nearly hydrostatic atmosphere (in which the force of gravity is balanced by the upward pressure gradient force), this increase in mean column density serves to add column weight. During the development stage of a mid-latitude cyclone, dominant weight-loss processes, such as net column divergence and warm advection near 200 mb overwhelmingly offset the tendency for air columns to gain weight from adiabatic and moist adiabatic cooling. But my point should now be clear: Rising air tends to make surface pressures higher, not lower. In other words, rising air actually works against the deepening of a mid-latitude cyclone; it serves as a "check and balance" on the overall intensity of the system.

Strong tropical cyclones, on the other hand, don't have this "check and balance" over their centers. Indeed, the predominant vertical motion over the center of a hurricane is downward. It's that downward motion that creates the eye of the storm, as shown in the visible satellite image of Hurricane Isabel from 1404Z on September 11, 2003 (below).

For the record, the eye is a roughly circular, fair-weather zone at the center of a hurricane. By "fair weather", I mean that little or no precipitation occurs in the eye and an observer looking upward in the eye can often see some blue sky or stars. The diameter of the typical eye ranges from approximately 30 to 60 kilometers (about 16 to 32 nautical miles across), but eye diameters as small as four kilometers (approximately two nautical miles) and as large as 200 kilometers (approximately 110 nautical miles) have been observed. For the record, Hurricane Wilma's "pinhole eye" was the smallest recollected by forecasters at the National Hurricane Center (two nautical miles) as the storm deepened to 882 mb (the lowest on record in the Atlantic Basin).

The "fair weather" in the eye can largely be attributed to the sinking air over the center of the storm. The downward motion in the eye is only on the order of a few centimeters per second, which suggests that the central core of strong tropical cyclones is approximately hydrostatic. Given that the compressional warming in the eye decreases the mean density of the central column of air in the eye (and thus its weight), we can deduce that subsidence contributes to the low central pressures observed in hurricanes. Of course, as the sinking air warms, relative humidity decreases within the sinking parcels, which promotes the clearing observed within the eye.

I should point out however, that the air does not uniformly sink within the eye of a hurricane. Dropwindsonde observations taken from the eye of a hurricane often reveal an inversion at an altitude of about one to three kilometers. To see what I mean, check out the representative temperature and dew-point soundings retrieved from dropwindsonde measurements in the eye of Hurricane Jimena (1991). The subsidence inversion near 850 mb is the telltale sign of downward motion in the eye of a hurricane, but the presence of this inversion means that air does not sink all the way to the ocean surface. The fact that air does not sink all the way to the surface explains why low clouds frequently exist in the eyes of hurricanes (although skies may not be completely overcast).

Regardless of the fact that air does not uniformly sink throughout the entire eye, the compressional warming associated with the subsidence in the eye is one contributor to the "warm core" of a hurricane. Meanwhile, deep, moist convection outside of the eye (in the eyewall--the partial or complete ring of powerful thunderstorms around the eye, and spiral bands--relatively long and thin bands of convective rains) also contributes to the warm core.

The image above gives you a "bird's-eye" view of the basic structure of a hurricane on radar. Note the spiral bands (yellow, orange, and red shadings) curving in toward the center of the storm, and the eyewall almost completely encircling the much lower reflectivity values (dark green and blue) in the eye. How does the deep, moist convection in the eyewall and spiral bands contribute to the warm core of the storm? Simply put, the air parcels rising in thunderstorm updrafts are initially very warm and moist (due to evaporation from warm tropical seas). As these parcels rise in thunderstorm updrafts, huge amounts of latent heat of condensation are released. Yes, air parcels cool as they rise, but the release of latent heat keeps them warmer than they otherwise would be, which keeps the air within a hurricane warmer than air at the same altitudes outside of the influence of the hurricane. Weaker tropical cyclones are also warm core systems because of the release of abundant latent heat (even though weaker systems don't have eyes--there's no organized compressional warming in the center of the storm).

All in all, within a strong tropical cyclone, the warm core generated by latent heat release and compressional warming can be quite substantial. For example, check out the cross-section of satellite-detected temperature anomalies from Super Typhoon Haiyan at 1726Z on November 7, 2013 (below).

The core of the warm anomaly approximately coincides with the eye of Haiyan, and at its peak in the middle and upper troposphere, temperatures were as much as 7 degrees Celsius greater than the environment surrounding the storm. Outside of the eye, the warm anomaly is weaker, but still spans hundreds of miles across the storm. Given the maximized warm core near the center of the storm, it becomes clear that hurricanes create large horizontal temperature gradients internally (especially at the interface of the eye and eyewall) during their development, even though they initially form in the weak horizontal temperature gradients that characterize the tropics. As you've learned, mid-latitude cyclones are just the opposite: They form in areas with large horizontal temperature gradients, and their circulations ultimately act to reduce horizontal temperature gradients over time.

Sustaining Tropical Cyclones

Now that we've established a key difference between tropical cyclones (which have a warm core) and mid-latitude cyclones (which do not, since they are characterized by rising motion over their centers and typically lack deep, moist convection near their cores), let's turn our attention to another key factor in the intensification of both mid-latitude and tropical cyclones--divergence aloft. You're already familiar with the role of divergence aloft in mid-latitude cyclones, supplied primarily by 500-mb shortwave troughs and 300-mb jet streaks, but divergence aloft plays an important role in tropical cyclones, too.

In order to help you visualize divergence aloft in tropical cyclones, allow me to introduce the secondary circulation of a tropical cyclone. As the name implies, tropical cyclones have two distinct circulations. The primary circulation, as you might expect, refers to rotation of air around the center of the storm. But, there's another circulation going on at the same time. In a basic sense, low-level air flows in toward the center of the storm, rises in thunderstorms within the eyewall and spiral bands, and flows (mostly) outward aloft, sinking around the periphery of the storm. This general circulation (in at the bottom of the storm, up, out at the top, and down around the storm's periphery) is the secondary circulation. To visualize this "in, up, and, out" process in the context of a strengthening hurricane, check out the slideshow animation below.

The divergence aloft in a healthy tropical cyclone acts to further reduce surface pressure by removing mass from air columns near the center of the storm. Ultimately, hurricanes intensify as a result of a positive feedback loop, albeit a completely different one than the self development process for mid-latitude cyclones. One of the salient features in the positive feedback loop for hurricanes is "scale interaction." In a nutshell, processes on the spatial scale of convection (thunderstorms, for example) work to amplify changes on a larger spatial scale (such as lowering surface air pressure in the eye of a hurricane). In turn, amplification on the larger spatial scale amplifies convection (thunderstorms), and the feedback loop is off to the races.

We'll delve much deeper into the details later in the course, but here are the basics of the feedback: As eye-wall thunderstorms mushroom upwards and intensify, the magnitude of the secondary circulation (and divergence aloft) becomes greater, as does subsidence and compressional warming in the eye. This all sets the stage for negative pressure tendencies near the ocean surface (surface pressure decreases with time), which draws more low-level air inward to rise in thunderstorm updrafts, and the cycle continues. The key to maintaining the whole process is sustaining organized deep convection around the core of the storm.

As you now know, tropical cyclones operate quite a bit differently from mid-latitude cyclone, so make sure that you understand the main contrasts between the two types of storms. To help you keep track of the major differences, below is a quick summary, highlighting the key differences between mid-latitude and tropical cyclones.

Key Differences Between Mid-Latitude and Tropical Cyclones

- Mid-latitude cyclones form in environments with strong horizontal temperature gradients, while tropical cyclones form in environments with weak horizontal temperature gradients (but they create strong horizontal temperature gradients internally).

- Air rises over the center of a mid-latitude cyclone, and thus, cools, which works against falling surface pressures. Over the centers of strong tropical cyclones, however, air sinks and warms via compression, which helps surface pressures decrease.

- The release of latent heat from deep, moist convection, and compressional warming from subsidence causes tropical cyclones to have a warm core. Mid-latitude cyclones, on the other hand, lack a warm core.

- Mid-latitude cyclones rely on divergence aloft to drive decreases in surface pressure. Low surface pressures in tropical cyclones, on the other hand, result from significant contributions from the warm core of the storm (low column density) and divergence aloft via the secondary circulation.

By now, I hope you're beginning to appreciate the differences between the mid-latitudes and the tropics. But, we're not done quite yet. Even the tools that tropical forecasters use are different! We'll start with map projections next. You'll quickly see that the map projections commonly used in the mid-latitudes don't work so well in the tropics!

Explore Further...

Mid-Latitude Cyclones with Eyes?

The centers of mid-latitude cyclones are typically quite cloudy due to the upward motion that occurs there. However, some mid-latitude cyclones (particularly those over the oceans), actually exhibit "eye-like" features during their mature phases. Such features occasionally become apparent when intense mid-latitude cyclones spin-up off the East Coastand aren't actually true "eyes" like those in tropical cyclones. Instead, these cloud-free regions in the center of a mid-latitude cyclone are referred to as "warm air seclusions." For example, an intense mid-latitude low off the coast of Long Island, NY, developed an eye-like, warm air seclusion at 15Z on April 16, 2007 (check out the 1515Z visible satellite image below).

Note that unlike tropical cyclones, no thunderstorms were present around the center of this eye-like feature (check out the 1515Z enhanced infrared image for confirmation -- high cloud-tops indicative of deep convection were certainly lacking). While the details of the formation of such features are well beyond the scope of this course, in a nutshell, air wraps cyclonically around the western flank of the low and traps warm air at the center of circulation, creating a warm air seclusion. The cyclone model, which describes the evolution of these types of cyclones, is called the Shapiro-Keyser Cyclone Model, and it differs somewhat from the classic "Norwegian" cyclone model you're familiar with. If you're interested in the Shapiro-Keyser Cyclone Model and warm air seclusions, here's one of the digestible research papers on this topic. Enjoy!

Can cyclones ever change type?

In order to thrive, tropical cyclones require organized thunderstorms around their centers. In contrast, mid-latitude cyclones require large horizontal temperature contrasts in order to intensify. With these contrasting characteristics in mind, you might assume that tropical cyclones can never crossover into the realm of mid-latitude cyclones, but that's not really true.

As tropical cyclones move poleward, they inevitably enter an environment where there are horizontal temperature gradients. Before dissipating, a tropical cyclone sometimes becomes "extratropical" or "post-tropical," transitioning from a system with thunderstorms around its center to a mid-latitude low-pressure system that derives its energy from synoptic-scale temperature gradients.

A good example of an "extratropical transition" can be seen with Hurricane Noel. Early on November 2, 2007, Hurricane Noel started to move poleward off the coast of Florida. To gain a sense of the overall weather pattern, check out the 06Z surface analysis. Noel's position is marked by the hurricane icon and note the cold front coming off the East Coast. On the 0615Z enhanced water vapor image, it's easy to see the high cloud tops and high concentrations of water vapor in the upper troposphere focused around Noel's center. As Noel advanced north-northeastward (check out Noel's track) toward the cold front later that night, the tropical cyclone became post-tropical as it became embedded in the temperature gradients associated with the front. The 09Z surface analysis on November 3, 2007, indicates the remnants of Noel (marked by the red "L") on the verge of merging with the front.

Another clue to Noel's post-tropical transition is the comma-shaped configuration of the high cloud tops on this enhanced water vapor image at 1515Z the next morning (November 3, 2007). This satellite presentation is consistent with the classic conceptual model of mid-latitude cyclones that you've learned. The National Hurricane Center noted Noel's transition in its last Noel advisory (5 P.M. EDT on November 2).

For the record, "tropical transitions" can occur, too, in which non-tropical cyclones change into tropical cyclones. Often, such cyclones simultaneously exhibit characteristics of both mid-latitude and tropical cyclones for a time (and are called "subtropical cyclones"), but we'll touch on these topics later in the course.

Map Projections for Tropical Forecasters

Map Projections for Tropical Forecasters ksc17Prioritize...

By the end of this section, you should be able to discuss the benefits and drawbacks of using Mercator and Lambert conformal map projections to track tropical cyclones (particularly, where each type of projection has limited distortion). Using a series of images with Mercator projections, you should also be able to calculate an approximate speed of tropical cyclone movement over a fixed period of time.

Read...

The fact that Earth is a sphere presents some hurdles for map-makers (and weather forecasters). Trying to accurately depict our spherical Earth on flat maps brings some real challenges, and the resulting process is always imperfect. Because of these imperfections, many types of map projections exist. Depending on the type of map projection, it is possible to minimize (or, in some cases, eliminate altogether) distortions in shapes, areas, distances and directions (the "Big Four" that map-makers worry about). But, no single map projection accurately preserves them all. Indeed, minimizing or eliminating distortions in one or two of the "Big Four" often results in gross distortions in the others.

Because a number of different projections exist, weather forecasters must always be aware of the benefits and limitations of viewing data displayed on various map projections. From your previous studies, you should be familiar with the polar stereographic projection, which is commonly centered on the North Pole. The benefit of such polar stereographic projections is that it allows forecasters to track the movement of weather systems in the middle and high latitudes over long distances (for example, check out this enhanced infrared satellite loop of the entire Northern Hemisphere displayed on a polar stereographic projection). It is, however, important for forecasters to get their bearings when looking at polar stereographic projections because compass directions are not preserved. For example, in the polar stereographic map below, the arrow off the Pacific Coast of the United States represents a wind blowing from due west (270 degrees). An arrow representing a due west wind off the East Coast of the U.S. would be oriented quite differently, though, because it still would need to parallel the nearest latitude circle.