Food and the Future Environment

Food and the Future Environment mjg8Course Structure

The course is offered fully online. The course content is broken into 12 interactive lessons with formative and summative assessments that are all available online.

Overview

The Future of Food is an introductory-level science course that emphasizes the challenges facing food systems in the 21st century, and issues of sustainability for agriculture and other food production activities as well as the challenges posed by food insecurity and modern diets to human health and well-being. For Penn State students, GEOG 3 is an integrative studies, inter-domain general education course. Students who started at Penn State prior to summer 2018 can apply these credits to either GS or GN.

This course is offered as part of the Repository of Open and Affordable Materials at Penn State. You are welcome to use and reuse materials that appear on this site (other than those copyrighted by others) subject to the licensing agreement linked to the bottom of this and every page.

Want to join us? Students who register for this Penn State course gain access to assignments and instructor feedback and earn academic credit. Official course descriptions and curricular details can be reviewed in the University Bulletin.

Section 1: Introduction

Section 1: Introduction azs2The first section of the course presents an introduction to the course content as well as some fundamental ideas that help you to understand food systems, their impacts on earth surface processes, their history, and their emergence as one of the dominant interactions between humanity and the environment. Module 1 introduces the food system concept and the nature of coupling between human society and natural systems in food production and consumption. We also emphasize the multiple disciplines of natural and social sciences needed to understand food systems. Then, Module 2 addresses the history and emergence of food systems, in examples such as the domestication of crops, a step in human history which is quintessentially both human and natural. Module 3 introduces the important subject of human nutrition with a food systems background, and in this final module of the section, you will learn the basic requirements for healthy nutrition, as well as current and emerging challenges for human nutrition in food systems.

Modules

- Module 1: Introduction

- Capstone Project Overview

- Module 2: History of Food Systems

- Module 3: Diet and Nutrition

- Capstone Project Stage 1

Section Goals

Upon completion of Section 1 students will be able to:

- Identify natural and human subsystem components within a food systems framework.

- Describe the concept of the Anthropocene and the history of human-natural food systems and explain several examples of the impacts of humans on the earth system as part of food systems.

- Employ a coupled-human natural systems framework to assemble and diagram basic relationships within examples of coupled natural-human food systems components.

- Combine the above abilities to initiate an original, group-authored analysis of a food system within a world region to evaluate linkages, critique the sustainability, and propose solutions for this food system and its components (the course capstone project).

- Describe the basic elements of a healthy diet from a scientific standpoint.

- Describe current major nutrition challenges and their immediate causes, such as nutrient deficiencies and calorie over-consumption.

- Relate current major nutrition challenges to social factors such as food access and changing diets in modern food systems.

Section Objectives

In order to reach these goals, we have established the following objectives for student learning. Upon completion of the modules within Section 1, you will be able to:

- Construct a concept map representing an example food system.

- Identify human and natural component parts of food systems.

- Apply systems thinking strategies in analyzing food systems at an elementary level, including assessing relationships between natural and human system factors that display key functions and characteristics of food systems.

- Identify sustainable and unsustainable characteristics of food systems.

- Identify component parts of food systems that embody natural vs. human subsystems, and production, transportation, and consumption function of food systems.

- Describe the major features of hunter-gatherers’ use of food and the environment.

- Define and describe the domestication of plants and animals in early agriculture.

- Define and give examples of spatial diffusion, adaptation, niche construction, and carrying capacity in environment-food systems.

- Define and describe each of the four (4) principal historical-geographic periods of environment-food systems.

- Give examples of early domesticated plants and animals and their region of domestication.

- Within a Coupled Human-Natural Systems framework, relate fundamental drivers and feedbacks in natural and human systems over prehistoric and historical time to the development and spread of agriculture and other changes in food systems over time.

- Relate the origins and current dominance of agriculture to the concept of the Anthropocene period presented in module one.

- Describe the basic categories of nutrients and how these contribute to human function and health.

- Describe the major changes taking place in diet/nutrition in rich and poor countries, respectively.

- Define the concept of food access and the term "food desert" as contrasted to the broader concepts of food security and food insecurity.

- Understand changes in thinking around healthy nutrition and basic principles that have remained.

- Use an online nutrition tool to analyze and compare diets and areas in which they are deficient or excessive in nutrients.

- Analyze why food access is an issue in modern food systems.

- Use a mapping tool to analyze and compare the situation of food access in cities.

Module 1: Introduction

Module 1: Introduction mjg8In the two introductory modules (1.1 and 1.2) of the course, we will introduce the main theme of the course: learning about food systems as systems that combine human social systems, with the natural earth system and earth surface processes, to fulfill the food needs of human societies. The objective is to prepare you to tackle learning about sub-components of these systems (e.g. water resources, soil management, adaptive capacity of food systems to climate change) in an integrated rather than a piecemeal way, which is essential to understanding the current function of food systems as well as proposing future solutions for these systems. During this introductory unit, you will also embark on the course capstone project that asks you to structure your learning about food systems of a particular world region. These introductory modules will also present the systems concept as a general way of thinking that applies especially well to food systems.

Goals and Learning Objectives

Goals and Learning Objectives azs2Goals

- Identify connections between human and natural components of food systems.

- Understand and apply systems thinking principles to food systems.

Learning Objectives

After completing this module, students will be able to:

- Construct a concept map representing two food systems.

- Identify human and natural component parts of food systems.

- Apply systems thinking strategies in analyzing food systems at an elementary level, including assessing relationships between natural and human system factors that display key functions and characteristics of food systems.

- Identify sustainable and unsustainable characteristics of food systems.

Module 1.1: The Future of Food: Course Overview

Module 1.1: The Future of Food: Course Overview azs2This course, The Future of Food, provides introductory-level learning perspectives on human and environmental systems of food and resource use, in order to understand challenges and opportunities. The goal of the course is to understand and be able to apply an integrated perspective on the environmental and human dimensions of environmental issues related to food production and consumption. The content of the course addresses both environmental and human systems of food and resource use to an equal extent. In the case of the first (environmental systems), you will learn about the geosystems and agroecology of soil, nutrients, crops, water, and climate that form the fundamental basics of food-growing environmental systems. In the case of the second (human systems) you will learn about factors such as population and the roles of culture, social interactions, economics, and politics. These multiple perspectives are integrated into the framework of "Coupled Natural-Human Systems" (the CNHS is used beginning in 1.2 (also called Coupled Human-Natural Systems or CHN). We will focus on current environment-food systems, while also including the past trajectories and future trends of food systems. The course also blends information and analysis of local-scale environment and food systems with a focus on the regional, national, and global scales, and asks you as a learner to apply this knowledge in a Capstone Project that you assemble over the course of the semester in collaboration with other students. The course features active learning in both online and classroom settings and a wide variety of learning materials and methods.

Food, Society, and the Environment: Coupled Human-Natural Systems

Food, Society, and the Environment: Coupled Human-Natural Systems azs2“We are what we eat.” We’ve all heard this common expression and may think of it in nutritional and biological terms: for example the way that the chicken or beans we consume are turned into muscle tissues. However, this simple phrase has a deeper meaning: Food production, food culture, and organization of food transport and consumption loom very largely in the way that our society "is". These food-related activities also strongly impact the earth's fundamental surface processes and ecosystems. So, we are what we eat, but in a societal as well as an individual sense. This wider vision of food as a driving presence within society is increasingly relevant as groups and individuals like you become more interested in the ramifications of their food for themselves and for the environment. This course is designed to provide you with the tools to understand the combined environmental and human dimensions of food production and consumption. To do so we must start with some simple questions and reflect a bit on how we can address them.

Where does our food come from? And, how can we make our food supply more sustainable? These two questions may seem simple, but they lead us to a range of considerations that are covered through the remainder of this course. As we consider these questions in each module, we'll explore a model of food systems as human systems in interaction with natural systems, or coupled human-natural systems (Fig. 1.1.2). As the name suggests, the concept of Coupled Human-Natural Systems (CHNS) tries to describe two major components that are involved in the production and consumption of food. The first component is the natural world and a set of interacting natural factors. Some of you may know the term ecosystem, and ecosystems developed from interacting natural components such as water, soils, plants, and animals (e.g. Fig. 1.2.1 in module 1.2) are the context for most food production. Throughout the course, we may also refer to the elements and processes of ecosystems as the earth system and earth system processes, or simply as the environment. These natural systems are a basic foundation of the food supply that we will learn more about in modules four through six (Environmental Dynamics and Drivers). The continued productivity of natural systems is evaluated as being crucial to sustainability, as you will see in the short reading below.

On the other hand, the two questions posed above involve the role of people, both as individuals in groups such as communities, institutions (including colleges and universities, farm and food processing businesses, and farmer organizations, for example) and political units such as countries. To introduce this dimension we often refer to this globally as the "human system" within a coupled human-natural system (Fig. 1.1.2.; a complete definition of human and natural systems are given in Module 1.2). Within the human system, factors such as styles of farming and food choices, tastes, economic inequality, and farmer and scientific knowledge that inform humans' management of ecosystem emerge from human cultural, social, economic, and political influences.

The end result of these interactions between human and natural systems are what we call a food system, which has has also been called an "environment-food system" (see the introductory reading on the next page) with "environment" pointing to the natural components and the "food system" pointing to the human organization needed to produce, transport, and deliver food to consumers, along with a host of cultural, regulatory, and other aspects of human society that relate to food. In terms of geography, the interactions of environment-food systems exhibit a huge range of variation across the world. As we all know this variation exists between countries, so that food and farming types can be associated with “Chinese food,” “French food,” “Peruvian food”, or scores of other examples. Farming and food also vary a great deal among regions within a country and sometimes even among local places, as we know if we compare a large dairy or grain farm with a fresh vegetable farm serving local markets here in the United States. Understanding the geographic variations of environment-food interactions is key to recognizing their increased relevance and importance to people and places.

Guided Introductory Reading: Why Environment and Food?

Guided Introductory Reading: Why Environment and Food? sjv13Introductory Reading Assignment:

- Read the brief section (pp 1-7) of Colin Sage's book "Environment and Food", entitled "Why Environment and Food?" (see the assignments page). The author explains why we are interested in considering food's relationship to the environment (the latter is what we are also calling "natural systems"). He presents a provocative and critical account of our relation to food in modern societies (human systems) and the need to think about food production and consumption patterns in relation to the environment.

- As you read, try to identify three to five main points of the reading, which is always a good practice when you read in this course and other courses.

- After reading the assignment, continue reading below and see whether your perceptions of this author's analysis agree with the main arguments we have noted below. You may have noted similar points, or additional ones not noted here.

Consult AFTER Reading:

First, consider the list below of some of the main ideas in the reading. Do these roughly agree with your list of main points? You may have identified additional points in the reading.

- The essential need of humans to eat has defined the relation of all societies to food production and the environment through history.

- Transformation of food production systems in the last 100 years has dramatically changed diets and societies' impact on the environment:

- Yields have increased with industrial methods and food for many in the world has become more available.

- However, diets have worsened in many cases so that human nutrition has suffered.

- Inequality in access to food based on wealth and poverty of consumers has continued.

- Negative impacts on the environment have multiplied, which is expressed in the large amounts of water needed to produce food, the strong dependence of food production on fossil fuels, and the contribution of food production to CO2 methane, and other greenhouse gas emissions that cause climate change.

- A sustainable food system, which is increasingly the vision promoted by some food producers and consumers, involves reducing fossil fuel use in food production, cutting waste of food in transport and consumption, and increasing the just distribution of food to consumers at all levels of wealth.

We can also think of the way that these main points fit into a diagram, sometimes called a concept map, like the one that is drawn here. As part of the final assignment or summative assessment for module 1, and in the capstone assignment for the entire course, you will be drawing concept maps of a food system example. This diagram may get you started on visualizing human and natural components of food systems and their interaction. You'll note that a concept map can start from a very preliminary drawing or rough draft (like this one), and gradually be reorganized as you learn more about a topic use an organizational principle like the coupled human-natural systems concept we present in this course.

Text description of the Figure 1.1.3 image.

The image is a hand-drawn concept map illustrating the interaction between human systems and natural systems within the context of food systems and sustainability. On the left side, labeled “Human System” in pink, several interconnected elements are shown: Sustainable food movements (with goals such as protecting resources, reducing waste, and promoting social equity), fossil fuels, farmers, food companies and retailers, agricultural and food system science, and modern consumers. Arrows indicate flows of products and relationships among these components, such as farmers providing products to companies and consumers, and fossil fuels influencing production. Additional notes highlight social challenges like need income, poor are left out, and issues of diet inequality, child labor, and poverty. On the right side, labeled “Natural System” in green, a box titled Environment lists key elements: landscapes, soil, fresh water, biological diversity, and livestock. Surrounding this are concerns such as climate change and greenhouse gases, as well as the need for healthier food. The diagram uses arrows and annotations to show how human activities impact natural resources and vice versa, emphasizing the complexity of food systems and the interplay between environmental sustainability, social equity, and economic factors.

Drastic Impacts of Food Production on Planet Earth: The Anthropocene

Drastic Impacts of Food Production on Planet Earth: The Anthropocene azs2After reading Colin Sage's brief introduction to the modern-day issues surrounding environment and food, you should be aware of the fact that food production by human societies has transformed the earth's natural systems. In fact, it is very difficult to understate the enormous impact that food production to support human societies has had on the surface of our planet as the earth's population has grown. Here are some of them:

- Humans have replaced permanent forests and wild grasslands with farm fields that allow much higher rates of soil erosion where the soil is not covered year-round. This has led to trillions of tons of soil being washed into rivers, lakes, and oceans, where it is unavailable as a key resource for food production.

- The expansion of farming and grazing has contributed to the reduction and elimination of wild forest and grassland species of plants and animals: the loss of earth's biodiversity.

- In some cases, previously unproductive dryland areas have been made highly productive through the movement of irrigation water into desert areas, allowing the expansion of human settlements.

- In other cases, elimination of forest in favor of farmland has contributed to the expansion of desert areas and worsening droughts.

- Humans have intensively fertilized cropland to make it more productive with manures and chemical fertilizers, leading to excesses of nutrients and pollution in many of the world's waterways.

- Farming and the other human activities that support modern food systems are major contributors to changes in earth's climate linked to increasing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere.

One term that is used to summarize these human impacts within the history of the earth is the Anthropocene, from Anthropos (human) and cene, a suffix used within the geologic timescale to denote the recent past. The Anthropocene has been proposed as a new geologic epoch because of the profound and unprecedented human alteration of earth's natural systems that we point to above. Scientists researching the Anthropocene tend to agree that it was the beginnings of agriculture that probably marked the onset of the Anthropocene. We will introduce you to the history of agriculture in Module 2. The concept of sustainable food systems that Colin Sage points to in the introductory reading are currently a major topic of debate and discussion in human societies and are a consequence of the sustainability issues that are a key feature of the Anthropocene. The idea of sustainable food systems is also a major topic of this course, and you will be asked to contribute to this discussion in your capstone project. The term Anthropocene helps us to appreciate the epochal change of the extent and degree of these changes. Yet these changes do not suggest or imply that all is lost, or that all cropping and livestock-raising are pervasively damaging to the environment. As you’ll see throughout this course there are already well-developed options worth considering and pursuing in order to expand sustainable environment-food systems.

Studies of the changes in the type of ecosystems that cover different areas of the earth or land cover (e.g. crop fields versus forest versus desert) allow us to appreciate the impact on earth during the Anthropocene (Fig. 1.1.4 below). We can see in the bar chart reflecting changes over time in land cover that farmed and grazed areas involved in food production for rising populations have expanded from less than 10% of earth's usable (ice-free) surface in the 1700s to over 50% in 2000, a stupendous change considering the size of earth's land area (similar expansion of human influence in food production in earth's ocean fisheries has also occurred).

Figure 1.1.4. A graph showing the global allocation of the ice-free land area, on all five continents, to human land use versus wild (bottom stippled bar section) across three centuries from 1700 to 2000, during the rapid expansion of human population in the Anthropocene.

(Approximate estimate of the percentages of global allocation in ice-free land area)

Year 1700:

- Wild (uninhabited) ≈ 49%

- Seminatural (e.g. inhabited forests) ≈ 45%

- Rangeland (grazed livestock, non-cropped) ≈ 1.5%

- Cropland ≈ 3%

- Villages ≈ 0.25

- Urban ≈ 0.25%

Year 1800:

- Wild (uninhabited) ≈ 45%

- Seminatural (e.g. inhabited forests) ≈ 45%

- Rangeland (grazed livestock, non-cropped) ≈ 5%

- Cropland ≈ 3%

- Villages ≈ 1.5%

- Urban ≈ 0.5%

Year 1900:

- Wild (uninhabited) ≈ 35%

- Seminatural (e.g. inhabited forests) ≈ 35%

- Rangeland (grazed livestock, non-cropped) ≈ 19.5%

- Cropland ≈ 8%

- Villages ≈ 1.75%

- Urban ≈ 0.75%

Year 2000:

- Wild (uninhabited) ≈ 24.5%

- Seminatural (e.g. inhabited forests) ≈ 20%

- Rangeland (grazed livestock, non-cropped) ≈ 32%

- Cropland ≈ 14%

- Villages ≈ 8.5%

- Urban ≈ 1%

Similarly important is that the Anthropocene, or the "human recent history of the earth" if we translate the word slightly, brings to our attention to not only the changes in natural systems or the environment but also the significant alterations of the human dimension of human-natural systems related to food. It’s safe to say that for nearly all of us this human dimension is significantly different than it was for our grandparents or even our parents. Some basic examples can be used to illustrate this trend. In the United States, for example, the population of farmers has continued to shrink. It is now less than 4 percent of the national population. At present this fraction, though generally declining worldwide, is somewhat higher in European countries and much higher in Asia and Africa. The continued importance of food-growing agriculture among large sectors of the populations in Africa and Asia, for example, creates different patterns of livelihoods (Fig 1.1.5a) and landscapes (Fig. 1.1.5b).

One important point: familiarity with environment-food systems through immediate experience among human populations, including you and your fellow learners in this course, is presumably at an all-time low. It’s also an interesting reflection on the human dimension of the Anthropocene. Other statistics could be quoted to show related trends. For example, the average amount of time being spent on food preparation is roughly one-quarter the standard allocation of time devoted to this activity 40-50 years ago. This course takes these statistics as a challenge and opportunity since environment-food interactions are both less-known than previously and, at the same time, have a very high level of importance to the environment and society.

Sustainability: Environments, Communities, and Economics

Sustainability: Environments, Communities, and Economics sjv13The guided reading in this module on concerns around "Environment and Food" and our consideration of the Anthropocene as an era defined by the dramatic expansion of food production on earth's surface lead us naturally to the concept of sustainability, which is a common term in much of our discourse in the present day, in many different settings from the coffee shop and classroom, to dinner tables and company boardrooms, to government offices. As we think about the increasingly obvious impacts of our food system on the global environment and on the social dynamics of global society, we are concerned that this food system needs to (a) be part of society and communities with adequate opportunities for all and just relationships among people and (b) not compromise the future productivity and health of earth's many different environments. As part of the introductory work of this first module, we ought to consider a definition of sustainability that is broad enough to encompass both human and natural systems, and geographic scales from communities to single farming communities to the worldwide reach of food production and transport in the modern global food system. We present below in figure 1.1.6 one relatively common definition of sustainability as a "three-legged stool" (we will return to this concept later in Module 10 when we return to food systems).

In the model of the three-legged stool, environmental sustainability reflects protecting the future functioning, biodiversity, and overall health of earth's managed and wild ecosystems. Community and social sustainability reflect the maintenance or improvement of personal and community well-being into the future, versus relations of violence and injustice within and among communities. In the case of food systems, this reflects especially the just distribution of food and food security among all sectors of society, the just treatment of food producers and the rights of consumers to healthy food, and the expression of cultural food preferences. Economic sustainability within food systems has often been conceptualized as relationships of financial and supply chains that support sufficient prosperity for food producers and the economic access of consumers to food at affordable prices.

Dividing the concepts of sustainability into three parts of an integrated whole allows us to think about food production practices or food distribution networks, for example, are sustainable in different aspects. Excessive water use or fossil fuel consumption, for example, are aspects of environmental sustainability challenges in food systems considered further on in this course. Meanwhile, issues of food access, poverty, and displacement from war, and their impacts on human communities and their food security are issues that combine social and economic sustainability, which will also be considered by this course. The three-legged stool is a simple, if sometimes imperfect, way to combine the considerations of sustainability into a unified whole. As you consider the sustainability challenges at the end of module one and in your capstone project, you may be able to use these three different concepts along with the concepts in the guided reading to describe the sustainability challenges of some food system examples. You may want to ask yourself, is this practice or situation environmentally sustainable? socially sustainable? economically sustainable?

Increasing Interest in Food Systems and Sustainability

Increasing Interest in Food Systems and Sustainability azs2Individuals, Communities, and Organizations Taking Action on Sustainability: Information Resources on Real-World Efforts

The interest in the sustainability of environment-food systems, as we've just defined them -- see the "three-legged stool" on the previous page -- has skyrocketed in recent years. A brief sampling of these issues involves the following:

- Health and Nutrition concerns over the nutritional quality and nutrient content of food and food-producing environmental systems

- Food security among approximately 1.1 billion persons around the world with low income and other limitations that do not allow them to access sufficient food.

- The need to design food and agricultural systems that can respond successfully to climate change.

We aim that this course will allow you as a learner to this rapidly expanding suite of interests while it offers background and the capacity to understand better and more fully these issues. You will pursue this aim through the readings and evaluations in this course, and also in completing a capstone project on the food system of a particular region.

One way to begin learning about this expanding interest is to consider the activities of individuals, communities, and governments as well as organizations ranging from nonprofits to international and global groups. In the case of individuals and communities, much interest is being generated by local food initiatives, such as farmers’ markets, and other local groups of producers and consumers seeking to improve environment-food systems. A variety of government agencies in the United States and other countries have also become increasingly involved in environment-food issues.

The United States Department of Agriculture, for example, now offers a focus on environment-food issues such as responses to climate change and dietary guidelines in its range of research and science activities. The USDA website also includes the compilation of data through its different research services that you will use in this course.

The United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), which is based in Rome, Italy, is one of a number of international organizations focused on environment-food issues. It addresses nearly all the topics raised in the course, as well as many others. The statistical branch of the FAO, known as FAOSTATS, is an important source of information on the international dimension of issues involving food and the environment.

Numerous non-profit organizations are involved in environment-food issues in the United States and in other countries. One of these organizations in the U.S., which is called Food Tank, periodically provides the lists of other organizations that it considers leaders in environment-food issues. In 2014, for example, Food Tank named the "101 Organizations to Watch in 2014”. This interesting list, complete with brief descriptions, includes a number of both well-known and lesser-known groups active in environment-food issues. Other organizations have greatly expanded their environment-food focus. National Geographic, for example, now has a major focus on environment-food issues. Its website includes an important section on food and water within the organization’s initiative on EarthPulse: A Visual Guide to Global Trends. This section includes a number of excellent global maps of environmental and food conditions, challenges, and potential solutions.

These resources may be a help to you as you consider not just the learning resources we present in this text, but the real efforts to promote environmental, social, and economic sustainability in food systems, which you will address in the final section of the course and in your capstone project.

Formative Assessment: Environment and Food Issues

Formative Assessment: Environment and Food Issues azs2Instructions

Look over Food Tank's "101 organizations to Watch in 2014".

Choose one organization from this website that treats the combination of environment-and-food issues. You'll need to be selective since some of the organizations specialize in food-related issues but have little emphasis on environmental one. Also, read the assignment from Colin Sage, pp. 1-8 on "Introduction: Why environment and food?" in Environment and Development that is one of the required readings for this module (see the assignments page)

Then,

- Write a brief overview description of the organization you chose from the Foodtank website, its summary goals in relation to the environment and food issues - distinct from the more detailed description of issues and factors below, funding source or sources, location and scope (local, national, and/or global), longevity (including when it was founded), and what you perceive as its intended audience and/or client or target population.

- After addressing these overview questions for the organization, continue and address briefly the following two questions where you can draw on the assigned reading from C. Sage:

- What factors or issues of importance to environment-food systems does it address - a more complete elaboration of its summary goals in the previous overview? (1 paragraph)

- How is sustainability defined and addressed by this organization? (1 paragraph)

Your writing should be between one and one and a half pages long, and no longer than two pages. When appropriate, you can relate the work of this organization to the other material in this introductory module regarding multidisciplinary approaches or the concept of the Anthropocene. Be sure to describe what types of environmental and food issues are being addressed by this organization, as well as the wider factors and sustainability questions.

Submitting Your Assignment

Please submit your assignment in Module 1 Formative Assessment in Canvas.

Grading Information and Rubric

Your assignment will be evaluated based on the following rubric. The maximum grade for the assignment is 25 points.

| Criteria | Score of 5 | Score 3 | Score 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Answer adequately addresses the organization's relationship to the environmental AND food issues as well as its understanding of sustainability and sustainability goals. | A clear description of both environment and food issues and sustainability and how the organization interprets the linkages between. | Some mention of both environmental and food issues addressed by the organization, and how sustainability is understood. | Little mention of any element or one of the elements missing. |

| Answer addresses summary details of the organization as requested in the assignment (e.g. food/environment goals, longevity, target audience or client group, etc.) | Complete mention of all elements clearly explained. | Mentions most elements | Mentions less than half of the elements. |

| The answer is legible, correct, and clearly written. | Clearly structured writing organized into themes, easily readable, with very few grammatical errors. | Some gaps in clarity or grammar errors, but significant effort is indicated, easily readable. | Difficult to read or many grammatical errors. |

| The answer relates the organization description to course content and reading. | Shows an understanding of environment and food issues as addressed by course materials, as well as relating these to other material in the module – multidisciplinarity or the Anthropocene. | Shows an understanding of environment and food issues as addressed by course materials | Shows incomplete understanding of environment and food issues as described in the course materials. |

| Length | Writing is sufficiently long and provides an adequate and interesting level of detail about the organization | Insufficient length to fully engage the topic. | Writing is only 1-2 sentences on all topics or relies on quick, outline-style response. |

Module 1.2: Food Systems Combine Natural and Human Systems

Module 1.2: Food Systems Combine Natural and Human Systems ksc17Introduction

Module 1.2 continues the goal of the introductory module, which is to introduce the course themes of integrated perspectives on the environmental and human systems that are related to food production and consumption. In the case of the first (environmental systems), the course places emphasis on the Geosystems and agroecology of soil, nutrients, crops, water, and climate that form the fundamental basics of food-growing environmental systems. In the case of the second (human systems) the course emphasizes factors such as population and the roles of culture, social interactions, economics, and politics. Module 1.2 builds on the concepts of multidisciplinarity introduced in Module 1.1 by introducing the Coupled Natural-Human systems framework as a conceptual tool where multiple natural and social disciplines are used to understand food systems. Building from simple examples of home gardens and hunting/fishing considered as natural/human systems, Module 1.2 provides an introductory description of food systems both as integrated production/transport/production chains and as interacting natural and human subsystems. Both of these themes will be deepened in Module 8, but the purpose here is to introduce them in basic form so that the subsequent modules on domestication, water, soils, and agroecology can utilize the framework and place even emphasis on both human and natural factors. Module 1.2 also advances the thesis (and key geosciences concept) that the global food system is a major area in which humans are transforming earth surface properties and processes during the Anthropocene. In Module 1.2 students are asked to complete a formative assessment in identifying introductory concepts in real examples of food systems which span local to global scales, and which take place both within and outside of the United States. The module concludes with a summative assessment that applies systems thinking and asks students to map a food system example and explore how relationships between parts of a food system are as important as knowledge about each part.

The Systems Concept

The Systems Concept sjv13What defines a system?

In this course, we will refer to the term "system" repeatedly, so it is worthwhile to think about how systems are defined. A basic definition of a system is "a set of components and their relationships". Rather than dwelling on this definition in the abstract, it's probably best to immediately think of how the definition applies to real examples from this course. An ecosystem is a type of system you may have heard of, in which the components are living things like plants, animals, and microbes plus a habitat formed of natural, urban, and agricultural environments, and all the relationships among these component parts, with an emphasis on the interactions between the living parts of the system and their interactions, for example, food webs in which plants feed herbivores and herbivores feed carnivores. A food system, as we have just begun to see so far, consists of food production components like farms, farm fields, and orchards, along with livestock; food distribution chains including shipping companies and supermarkets, and consumers like you and your classmates, with myriad other components like regulatory agencies, weather and climate, and soils. In the case of food systems we have already pointed out how these can be considered as human-natural (alternatively, human-environment) systems, where it can help to see the system as composed of interacting human components (societies, companies, households, farm families) and natural components like water, soils, crop varieties, livestock, and agricultural ecosystems.

Behavior of Complex Systems

Systems that contain a large number of components interacting in multiple ways (like an ecosystem, above, or the human-natural food systems elsewhere in this text) are often said to be complex. The word "complex" may have an obvious and general meaning from daily use (you may be thinking "of course it is complex! there are lots of components and relationships!") but geoscientists, ecologists, and social scientists mean something specific here: they are referring to ways that different complex systems, from ocean food webs to the global climate system, to the ecosystem of a dairy farm, display common types of behavior related to their complexity. Here are some of these types of behaviors:

- Positive and negative feedback: the change in a property of the system results in an amplification (positive feedback) or dampening (negative feedback) of that change. A recently considered example of positive feedback would be that as the arctic ocean loses sea ice with global warming, the ocean begins to absorb more sunlight due to its darker color, which accelerates the rate of sea ice melting.

- Many strongly interdependent variables: this property results in multiple causes leading to observed outputs, with unobserved properties of the system sometimes having larger impacts than we might expect.

- Resilience: Resilience will be discussed later in the course, but you can think of it here as a sort of self-regulation of complex systems in which they often tend to resist changes in a self-organized way, like the way your body attempts to always maintain a temperature of 37 C. Sometimes complex systems maintain themselves until they are pushed beyond a breaking point, after which they may change rapidly to another type of behavior.

- Unexpected and "emergent" behavior: one consequence of the above three properties is that complex systems can display unexpected outcomes, driven by positive feedbacks and unexpected relationships or unobserved variables. Sometimes this is referred to as "emergent" behavior when we sense that it would have been impossible to predict the behavior of the system even if we knew the "rules" that govern each component part.

To these more formal definitions of complex systems, we should add one more feature that we will reinforce throughout the course in describing food systems that combine human and natural systems, which is that drivers and impacts often cross the boundary between human or social systems and environmental or natural systems (recall Fig. 1.1.2). Our policies, traditions, and culture have impacts on earth's natural systems, and the earth's natural systems affect the types of human systems that develop, while changes in natural systems can cause changes in policies, traditions, and culture.

For more information on complex systems properties with further examples, see Developing Student Understanding of Complex Systems in Geosciences, from the On the Cutting Edge program.

On the next page, we'll see an interesting example of complex system behavior related to the food system in India.

Complex Systems Behavior: An Example from India

Complex Systems Behavior: An Example from India azs2The Indian Vulture Crisis: An Example of Complex Systems Behavior

The "Indian Vulture Crisis" may or not be a familiar term to you, but it is important enough to the history of modern India that it has involved dozens of research experts as well as major changes in wildlife, human health, and government policies, and now has its own Wikipedia page (Indian vulture crisis) that you can browse. It is also an interesting example of complex systems behavior that involves food systems and unintended consequences of veterinary care for animals. The main causal links are outlined below in figure 1.2.2, and the narrative of the crisis goes as follows:

Beef cattle are hugely important to Indian food systems even though they are usually not consumed by adherents of the majority Hindu religion (however, Indian Christians and Muslims, for example, do consume beef). Cattle are also widely used as dairy animals (think: yogurt and clarified butter as important parts of Indian cuisine) and are even more important as traction animals (oxen) to till soil for all-important food crops by small-scale farmers across India. Because of their importance and to treat inflammation and fevers in cattle, in the 1990s the drug diclofenac was put into widespread use across India. However, timed with the release of this medication, a precipitous drop in the population of Indian vultures began, which became the fastest collapse of a bird population ever recorded. Vultures are not valued in many parts of the world, but scavenging by vultures was the main way that dead animal carcasses were cleared from Indian communities, especially in the case of beef cattle where the meat is not consumed. It was not until the 2000s that the cause of vulture population collapse was discovered to be the diclofenac medicine administered to cattle, which is extremely toxic to vultures eating dead carcasses. However, the consequences of this population collapse did not end with the solving of the mystery of the vulture population collapse, which was already a tragic and unforeseen consequence. Rather, the fact that vultures are a key part of a complex system resulted in further unforeseen consequences in both human and natural parts of the Indian food system. A few of these are shown in figure 1.2.2 below: first, since vultures are in fact an ideal scavenger that creates a "dead end" for human pathogens in rotting carcasses, and since they were no longer present, water supplies suffered greater contamination from carcasses that took months instead of weeks to rot, leading to greater human illness. Second, populations of rats and dogs, which are less effective carcass scavengers, expanded in response to these carcasses and the lack of competition from vultures, which resulted in dramatic increases in rabies (and other diseases) due to larger dog and rat populations and human contact with wild dogs. This is significant since more than half of the world's human rabies deaths occur in India. Finally, the vulture crisis even had implications for religious rituals in India: people of the Parsi faith, who practice an open-air "sky burial" of their dead where the body is consumed by vultures, were forced to abandon the practice because of hygiene concerns when human bodies took months instead of weeks to decompose. A final consequence of these problems was that the drug diclofenac was banned from use in India, Nepal, and Pakistan in hopes of helping vulture populations to revive. This final turn of events is an example of the human system responding to the unforeseen consequences. Additionally, alternatives to these drugs have been developed for veterinary use that have no toxicity to vultures.

Note the properties of complex systems and human-natural systems exhibited by this example. Farmers sought mainly to protect their cattle from inflammation and speed healing in service of the food system, while pharmaceutical companies sought to profit from a widespread market for an effective medication. The additional, cascading effects of the human invention diclofenac, however, were dramatic, far-ranging, and in some cases unexpected, because of the many interacting parts in the food systems and ecosystems of Indian rural areas: cattle, groundwater, wild dogs, and human pathogens like rabies. The crisis eventually provoked responses from the human system, with impacts on human burial practices among the Parsi, laws banning diclofenac, and development of alternative medications. The search for sustainability in food systems, like those you will think about for your capstone regions, involves designing and choosing adequate human responses to complex system behavior.

Complex Systems and Interdisciplinarity

One final note on this example is to point out that to fully understand the Indian vulture crisis a large number of different disciplines were brought to bear: we need cultural knowledge about the beliefs and practical usefulness of both cattle and vultures in India. We also need biological knowledge about drug toxicity to wildlife, pathogens, groundwater contamination by microbes, and rat and dog populations. We also need policy expertise to think about transitioning food systems to less toxic alternatives to current practices. And all of these disciplines needed to be brought together in an integrated whole to assemble the diagram shown in figure 1.2.2. The purpose of this text and this course on food systems is to help you to develop some of the skills needed for this sort of interdisciplinary analysis of human-environment or human-natural systems.

Food Systems as Human-Natural Systems

Food Systems as Human-Natural Systems azs2Food System Examples from Household Gardens to Communities and Global Food Systems

Some of you in this course, perhaps even many of you, have had the experience of growing herbs or vegetables (Fig. 1.2.3) or keeping chickens for eggs or animals for meat. Although dwarfed by the enormous dimensions of the global food system, home food production is still a significant part of the food consumed by billions of earth's inhabitants. In other cases, small-scale fishing and hunting provide highly nutrient-dense foods, and coexist with modernized and industrial food systems, as any fishers and hunters in the class may be able to attest. These experiences of food production for personal or family consumption show natural-human interactions in a very simple way. To grow vegetables or hunt or raise animals means bringing together natural factors (seed, animal breeds, soil, water, fishing and hunting ranges, etc.) and also human factors (e.g. knowledge of plants, livestock, or wild animals, government policies) to gain access to food, as well as food storage and preparation, markets for tools and seeds, or human-built infrastructures like a garden fence or a chicken coop. This same interaction between natural and human factors is evident at a larger scale in the photo in Figure 1.2.4, which shows a landscape that has been transformed by a human community for food production.

Beyond these experiences of auto-sufficient food production and consumption, however, most of humanity also currently depends on global and local versions of the food system which features a web of suppliers, producers, transporters, and marketers that supply all of us as food consumers. Compared to gardening, catching trout, or keeping chickens, these food systems together form a far more complex version of the interactions between natural and human factors that produce and transport the food that we then consume as part of global and local food systems.

One way of viewing these regional and global food systems is that they can be divided by the type of activity in relation to food, and dividing them into components of food production, food transport, and food consumption (Fig. 1.2.5). Like other diagrams we've seen so far, this diagram can be considered a concept map showing relationships between the different components of a food system. The main arrows show the flow of food through the system from the managed natural environments used to produce food and the end result of nutrition and health outcomes. There are some unseen or implicit relationships here as well, like the way that farming practices, technology, communication and education, and other attributes of human societies support the functioning of a food system, and are included in the outer system boundary.

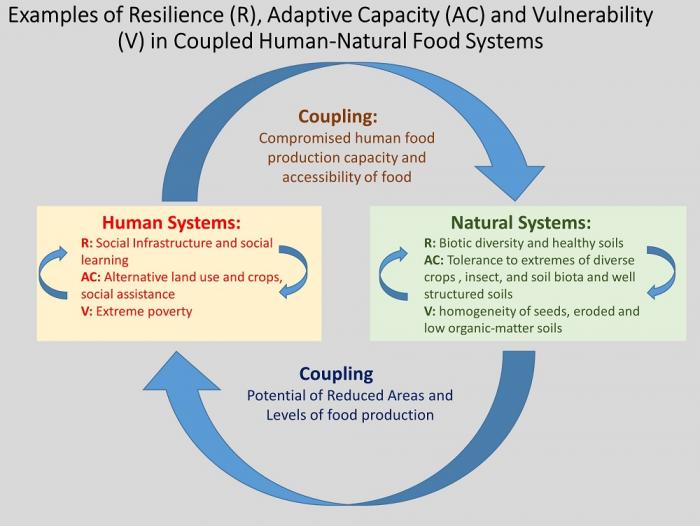

In addition to this more linear or "conveyer belt" portrayal of food systems delivering nutrition from natural resources, we may also be interested in thinking about the dramatic impacts humans have made on earth systems during the Anthropocene, discussed in module 1.1. In that light, we know that these natural systems may either be sustained or degraded by management, an important response that either maintains or undermines the entire food system. For this purpose, we may be interested in a food system diagram that makes the interactions among human and natural systems very explicit. Below in figure 1.2.6 is a version of a Coupled Human-Natural Systems diagram -- again, a concept map of sorts -- developed by an interdisciplinary group of social and environmental scientists (Liu et al. 2007) to represent the human-environment interactions in food systems.

This diagram highlights internal interactions within both the natural and human components of the food system. The natural components of food systems shown here are those we will tackle first in the first part of the course, while the latter half of the course will address the human system aspects of food systems and human-environment interactions shown as the large arrows connecting these two major components. As we saw in comparing home garden production, smallholder production landscapes and global food production chains above, food systems and their components are highly varied. However many similarities apply across the different components, actors, and environments of the food system:

- Food systems modify the natural environment and capture the productivity of the earth’s natural systems to supply food to human populations. Globally they create huge changes in the earth’s surface and its natural populations and processes.

- As portrayed in Figure 1.2.6, despite their complexity, food systems often involve coupling between human management and the response of natural systems. As pointed out by author Colin Sage in Module 1.1, the response of natural systems to human management can create sustainability challenges in food systems.

- Food systems involve the production, transportation, distribution, and consumption of food (Figure 1.2.5). The scale of these three processes can differ among food systems, which can be local, regional, and global.

- Food systems are examples of complex systems: they involve many interacting human and natural components, as well as important variability, for example, droughts, soil erosion, population changes, and migration, and changing policies. All of these affect the natural and human systems and can disrupt simple cause and effect relationships, in spite of the large-scale drivers and feedbacks shown in figure 1.2.6.

Knowledge Check

Module 1 Summative Assessment Overview

Module 1 Summative Assessment Overview azs2Summative Assessment: Concept Mapping and Assessment of Food Systems

First, download the worksheet to understand and complete the assessment. This assignment will require you to draw on your reading of this online text from module one, as well as several options for case studies where we have provided brief descriptions and audiovisual resources (radio clips, videos, photos) that describe these systems. You will accomplish two parts of an assignment that will not only evaluate the learning objectives for module one but will also give you practice in skills you will need to complete your capstone project. These two parts are:

- Draw a concept map of the system that distinguishes between human and natural components or sections of the system (an example is given below)

- Fill in a table that identifies some key components, relationships, and sustainability concerns for this system.

You will complete this assignment for your choice of two food system examples, as described in the detailed instructions below. You will first read, then draw a concept map, and then fill in a table with short responses.

Instructions

- Choose ONE national to global food system example and ONE local to regional food system example from the options that follow this assignment page in the text (see links in outline view at right, or the link to the next page at the bottom of this page). National to global food system examples are Pennsylvania Dairy, Colorado Beef Production, and Peruvian Asparagus, while local to regional examples are the Peruvian smallholder production and New York City greenmarkets examples. Read the descriptions of the system, which may include photos, videos, audio clips, or visiting other websites. Completely read through the description of the two systems you have chosen (one national/global and one local/regional), including these external links before continuing on to the following steps (though you may certainly return to the descriptions as needed). You are welcome to consult other resources online regarding the system you have chosen since that is a skill that will be helpful when embarking on data gathering for your capstone project.

- Using a sheet of paper, or composing in PowerPoint, develop a concept map of only ONE of the systems you chose, subject to the following guidelines:

- Title your concept map with the name of the system you are describing (among the five described on the following pages) and put your name on the diagram.

- Before you begin your concept map, draw a vertical line in your diagram to distinguish between Human and Natural components of the system to right and left, drawing on Fig. 1.2.6, 1.2.7 below, and 1.1.3 (the last one is the concept map example from the guided introductory reading by Colin Sage). However, you do not need to make your diagram look like the highly schematic diagrams in the text of the previous pages (see rather Fig. 1.2.7 below) -- you should include components that are discussed in the examples on the following pages, and connect them in the way that makes sense to you.

- Your concept map should be legible, but it does not need to be extremely neat since it reflects a first attempt to characterize a system. Additional components and relationships will occur to you as you draw, and you may need to squeeze them in. Therefore, leave space as you begin your diagram. If you feel your map becoming too hard to understand, please do compose a second "clean" copy.

- Remember that systems are defined as components and the relationships between them. If you are having trouble thinking of what to draw, think what the components are in the system (these can be boxes or ovals), and then how they are related (these may be labeled arrows)

- Below in Fig. 1.2.7 is an example of a concept map drawn from a food production system producing field crops (wheat, oats, barley, soybeans) and hogs for pork in Western France. Material for this concept map is drawn from Billen et al., 2012, "Localising the nitrogen footprint of the Paris food supply"1

Text description of the Figure 1.2.7 image.

The image is a hand-drawn concept map illustrating the interaction between human systems and natural systems in global food production and distribution. The diagram is divided into two sections: Human (labeled in red on the left) and Natural (labeled in green on the right). On the human side, key elements include European consumers, global shipping, farm management knowledge, and food processing and distribution companies, which are linked to products such as meat products and baked goods. Arrows show relationships such as government regulation for food safety and the role of companies in supplying consumers. On the natural side, components include soybean farms (Brazil), good climate for farming, pigs and pig farms, crops and crop farms (wheat, oats, barley), and good soils and flat land. Environmental concerns are noted, such as overuse of manure and fertilizer pollution, and the impact on rivers, estuaries, and coastlines, with an emphasis on regulation of water pollution. The map uses arrows to demonstrate how natural resources and farming conditions support agricultural production, which then connects to human systems through shipping, processing, and consumption. This visual emphasizes the complex interdependence between environmental factors and human activities in sustaining global food systems.

- Fill in the table on the worksheet with short answer responses regarding the two food systems you have chosen. The worksheet asks for responses in the following areas:

- Identify two natural components of the food system.

- Identify three human components of the food system.

- Tell how products from the system are transported to markets or to households for consumption.

- Name one sustainability challenge for the system, and state whether it represents a challenge in the area of environmental, social, or economic sustainability.

Once complete, use the worksheet as a guide to complete the Summative Assessment quiz.

National to Global Scale Option 1: Pennsylvania Dairy Sector

National to Global Scale Option 1: Pennsylvania Dairy Sector azs2Overview

Pennsylvania is the fourth largest state in the nation for milk production, after California, Wisconsin, and New York. Cows produce about 1.3 billion gallons of milk every year in Pennsylvania. Interestingly, 99% of Pennsylvania’s dairy farms are family-owned, which is in contrast to states such as California where large industrial dairies dominate production. On most conventional Pennsylvania dairy farms cows are fed forage crops that are grown on farms such as fermented chopped maize plants (silage) and alfalfa. These on-farm forages are mixed with other feed components that are imported to the farm to optimize milk production. There is also an expanding organic dairy sector in Pennsylvania that uses grazing whenever possible to satisfy the U.S. National Organic Program's regulations and organic philosophies of animal management (e.g. Fig. 1.2.8). Pennsylvania’s relatively good soils, temperate climate, and proximity to Eastern U.S. markets have helped to make dairy farms a dominant presence in Pennsylvania agriculture. Farms generally are on flat to hilly topography in what was originally forest, and patches of forest are still very common on steeper terrain throughout Pennsylvania. Manure produced by dairy cows is recycled into the soil to provide crops with nutrients. Farmers have to manage the application of manure and other fertilizers so that nutrients are best used by the crop and do not pollute waterways, which has been a major issue for water quality in the Chesapeake Bay downstream of Pennsylvania farms. Milk produced on these dairy farms is gathered into central processing plants and is then distributed to stores for purchase for consumers, or bought by other dairy industry manufacturers such as yogurt and cheese plants.

Be sure to also explore the following website to gain more insight on Pennsylvania’s dairy sector as part of the food system in order to successfully build your concept map and fill in the table items in the assignment:

National to Global Scale Option 2: Colorado Feedlot Beef Production

National to Global Scale Option 2: Colorado Feedlot Beef Production azs2Overview

Colorado Beef Production: A Tale of Two Feedlots

Beef production on Colorado’s high plains. Few topics arouse as much debate in conversations around the current trends, sustainability, and alternatives in food systems as meat consumption, and especially feedlot beef consumption which requires relatively large amounts of water and energy to grow the feed necessary for cattle production using feedlots. This remarkable if somewhat older video presents in a matter-of-fact way the practices, infrastructure, and modification of nature involved in beef production at small and very large scales on the high plains of Colorado (Warning: this video shows brief scenes from a slaughterhouse, e.g. cutting of carcasses). Watch for details about the use of water in a dryland environment, how feed is acquired in both systems to fatten animals, the use of technology to maximize the weight gain of animals, and the details of transport to market.

Video: Colorado Beef Production 1990 (FWU) - English(14:53)

National to Global Scale Option 3: Asparagus Production in Peru

National to Global Scale Option 3: Asparagus Production in Peru azs2Overview

International Production of Asparagus in Peru for the Global Food System

Starting from modest beginnings and export of asparagus from Peru to Denmark in the 1950s, the industrial-scale asparagus sector in Peru’s dry coastal valleys (especially around the city of Ica, Peru) grew rapidly in the 1990s into one of the premier examples of a globalized export vegetable sector (Fig. 1.2.9), able to occupy a large percentage of the world’s off-season market in asparagus when producers in the northern hemisphere are not producing asparagus (FAO 2007). The asparagus sector in Peru takes advantage of the extremely dry climate to make asparagus plants go dormant in the same way that winters in the northern hemisphere make the perennial asparagus plants die back so that they create new edible shoots in the spring. When a field of Peruvian asparagus is ready to go into production, irrigation from rivers and river-fed water tables in coastal valleys is turned on, and a flush of asparagus shoots grows, is harvested using labor that is relatively cheap on a global scale, and immediately flown in refrigerated containers to markets in the rest of the world, chiefly Europe. Asparagus is also notable for being a delicacy among U.S. and European consumers, with a sort of star status among gourmet eaters (see e.g. Peruvian Asparagus) Industrial-scale asparagus producers in Peru were able to achieve this scale of production and access to the global market via support from the Peruvian government, the help of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and their own resources and investment, based on earlier successes in the production of cotton in irrigated valleys (FAO, 2007). Interestingly, Ica asparagus growers organized several international tours to learn industrial methods of production in Europe and the U.S. and adapt them to their own region. However, the large scale of production and amounts of water needed are straining water supplies in the Ica region and have prompted objections regarding water supplies for other uses and the environment. Further, expansion of irrigation in Ica has been based on dam-building in upriver sites which alters ecosystems and water rights for other farmers in these valleys. The abundant supply of migrant labor from the Peruvian highlands and the economic power of the growers has also led to labor relations that are often quite unfavorable to workers.

Readings

Before drawing your concept map and filling in the table information for this assignment make sure to read the following news piece about Peruvian Asparagus from to learn more about the Peruvian asparagus industry and concerns about fresh water supply: Peru water wars threaten export boom.

You may also want to consult this brief from an industry news site covering the global fresh fruit and vegetable trade, detailing how asparagus is the most common Peruvian product shipped by air: Peru: Asparagus is the most exported product by air

Optional Reading

Diaz, Luz Rios. 2007. Agro-industries characterization and appraisal: Asparagus in Peru. Rome: FAO, 56 p.

Local to Regional Scale Option 1: New York City Green Markets

Local to Regional Scale Option 1: New York City Green Markets azs2Overview

A Regional Food-shed Direct Marketing of Local and Small Scale Farm Production: The New York City Green Markets

Many in the class will be familiar with the recent growth of farmers' markets and other forms of direct marketing in which farmers sell more directly to consumers to capture a greater percentage of the final purchase price. This includes mail-order grass-fed beef from South Dakota, organic farms, and other small farms selling at open-air markets in any given small and medium city, and medium to large scale farms that produce for multiple restaurant accounts in large cities. The New York City greenmarkets (Fig. 1.2.10) are an excellent and long-standing example of this trend, starting with a few street corner vegetable markets and growing into an important hub of the Grow NYC sustainability movement in New York. The Grow NYC website Greenmarket Farmers Markets documents that over 30,000 acres of farmland as well as small fishing operations near New York City form a ‘foodshed (analogous to a watershed feeding to a larger water body) that has made important inroads towards greater access to locally or regionally produced food with more sustainable practices, including participation in food assistance programs that strive to provide greater access to lower-income New Yorkers. Greenmarkets thus provide a growing, if small, proportion of New York City’s food supply.

Vegetable and livestock producers that participate in New York City greenmarkets are in many ways sustaining and building on the legacy of small truck farms that for generations utilized fertile farmland surrounding many eastern cities (think of the sometimes mysterious identity of New Jersey as the ‘Garden State’). Today these farms generally have land sizes of 5 to 50 acres, much smaller than the farm sizes of Midwestern grain farms or California industrial vegetable production. They are comparatively diverse farms in terms of combining many different products (including eggs and meat) that can be sold for relatively advantageous prices together in a farmers market. Farms like those in the Hudson Valley North of New York City utilize flat, deep soils adjacent to river floodplains that are excellent for long-term production of crops if they are well cared for. These farms are also able to recycle relatively abundant urban wastes from dense urban and suburban populations (e.g. green wastes, manure from neighboring small livestock farms, city and county composting programs) that are used to keep soils extremely productive by global terms. In fact, some of these farms may face some of the same problems of nutrient excesses presented in the case above on Pennsylvania dairy farming systems. They also are able to grow crops for the sole purpose of adding organic matter to the soil and covering the soil in the winter (cover crops) that help to keep soil quality high. Produce and animal products are trucked directly to green market sites in New York City or to pick-up points for subscription-based Community-supported agriculture programs.

Local to Regional Scale Option 2: Diversified Smallholder Production in the Peruvian Andes

Local to Regional Scale Option 2: Diversified Smallholder Production in the Peruvian Andes azs2Overview

In contrast to the highly specialized and industrialized production of Peruvian asparagus for the global market (above), smallholders in the Andean Mountains of Peru integrate a wide variety of livestock and crop types on their farms, from llamas to sheep to dairy cattle, and from native potato varieties to maize as well as legume grains and forages and vegetables. They also place a high priority on self-sufficiency in many food crops, balanced with sales to local (e.g. within community barter and purchase on community market days) and regional (e.g. wholesale to regional intermediary buyers and markets, Fig. 1.2.11). The variety of crops, livestock, and production is partly explained by the varied elevation and soil types found in the mountainous Andean environment. A high diversity of products, production strategies, and market versus consumption destinations for agricultural production has thus emerged in modern Andean societies as a way to adapt to both the natural risks of a mountain environment (e.g. drought, frost, hail) and the opportunities and challenges of a complex and fluctuating market that very often does not favor the farmer’s interests.

The integration of small livestock herds in these systems is very important and allows farmers higher value products such as wool and meat that can be used for short-term cash needs. Grazing livestock also allows them to “harvest” manure nutrients via grazing on high-altitude grasslands. When animals are penned into night-time corral areas they produce manure that is stored for use in fertilizing crop fields. Farmers also apply limited amounts of modern chemical fertilizers to their crops, especially those destined for regional markets. Increasingly, farm communities are banding together using strong and complex community government schemes to win government funding for and build community-wide irrigation schemes that are fed by mountain stream systems. These irrigation systems, some very extensive, are used for adaptation to drought years, expansion of cultivated land or irrigation of fodder crops to feed animals year-round in small intensified dairy schemes. The expansion of small dairy enterprises has been driven by increases in the price of milk in Andean countries from growing urban populations. Because of the preponderance of sloped land in these mountain systems, soil productivity for these Andean smallholders is very vulnerable to erosion during the intense rainy season of the Central Andes. Climate change has also tended to accentuate the severity of climate risks in these systems.

Capstone Project Overview

Capstone Project Overview azs2Future of Food Capstone Assignment: Analysis of Regional Future Food Scenarios

Course-level Learning Goals

- Describe and assess the soil, biological, and water resources and climatic conditions that support food production systems.

- Analyze how human food systems significantly alter earth's ecosystems, specifically the biological, soil, and water resources.

- Evaluate the resilience of food production systems in the context of future climate, human population growth, and socio-economic factors.

Summary of Capstone Assignment

At the beginning of the semester, you will select a food region. Throughout the semester, you will study different aspects of the food systems of your assigned region. By the end of the semester, you will have prepared a paper about your assigned food region that explores and analyzes the current status and the future resilience and sustainability of the food systems in your assigned region.

Capstone Overview

In order to assess your understanding of the interdisciplinary topics covered in this course, The Future of Food, you will need to demonstrate your mastery of the course learning objectives via the completion of a capstone project. The capstone project requires that you assess the current status of the food systems in an assigned region, and consider the food systems in your assigned region for future scenarios of human population growth and increased temperatures.

The capstone assignment is broken down into five stages that allow you to develop your assessment of the current status of the regional food system gradually as you progress through the course material. At the end of every third module, you will complete an assignment (or stage) designed to help you gather and organize the information you will need to assess future food scenarios. Each stage has an associated worksheet, which includes a table containing questions and suggestions for where to go to gather information or data.

During week 2, you will decide on a capstone region and gain instructor approval. In deciding this please consider a region with (a) significant agricultural production, (b) clearly defined boundaries of interest, (c) enough information published in reputable sources to collect enough information related to course content, and (d) are not too big of an area. To clarify the last point, usually, people choose a selection of small states or provinces that around about 100 miles in diameter.

Outline of capstone stages

You will find a worksheet associated with each stage that outlines in detail the data and information you should be gathering at that stage. The final Stage 5 document provides details regarding what should be included in your final paper or on your final web page. The stages will progress through the semester as outlined in the diagram below (please ignore parts about individual assessments and websites, as these have been removed from the course):

Text description of the Capstone Stages Outline image.

This image is an outline of the Capstone Project as follows:

Stage 1: Introduction to your region, history and diet/nutrition.

- Complete at the end of Module 3

- Initial data gathering (ppt & worksheet) documents

State 2: Water, nutrients, and crops

- Complete at the end of Module 6

- Continue work on data gathering -submit ppt and worksheet

State 3: Soil/crop management, pests, and climate change

- Complete at the end of Module 9

- Submit updated ppt and worksheet

State 4: Food systems and resilience, adaptive capacity and vulnerability (RACV)

- Complete at the end of Module 11

- Submit updated ppt and worksheet

State 5: Final future food scenario website production

- Submit a rough draft for peer review

- Submit your final Capstone Paper

Capstone Grading

At the end of the semester, you will create a paper or website about your region. More details are provided in the Stage 5 worksheet. Your paper will include the following information

The Final Capstone Assignment (Stage 5) - Paper on your region's future food scenario

Grading Information and Rubric for Final Capstone Paper:

| Criteria | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Completeness of paper & all supporting documents: Conforms to all instructions and guidelines | All specific instructions are met and exceeded; no components are omitted. | Most instructions are met with only 1 to 2 minor omissions | Some components are present with the omission of several key elements | Missing most components of the project, minimal conformity to guidelines. |