Lesson 5: Color, Classification, and Choropleth Symbolization

Lesson 5: Color, Classification, and Choropleth Symbolization mxw142The links below provide an outline of the material for this lesson. Be sure to carefully read through the entire lesson before returning to Canvas to submit your assignments.

Note: You can print the entire lesson by clicking on the "Print" link above.

Overview

Overview mxw142Welcome to Lesson 5! Last lesson, we learned about techniques that cartographers employ to visualize Earth’s terrain. This week, we begin to focus on a more statistically driven type of thematic map: choropleth maps. Choropleth maps are a very common thematic map type. To design them properly, an adequate understanding of other important topics in cartography, such as data standardization and classification methods are needed. Choropleth maps also typically employ color in their design: in this lesson, we discuss color in-depth. You will learn about the different ways in which we can model color space, and how visual perception constraints - both in the general population, and in those with color-vision impairments - influence map perception.

In Lab 5, we'll explore how choosing a different color scheme and data classification method can alter the way the information is presented and how readers interpret that information. We’ll also learn how to make maps that work well in pairs—a common task that is often significantly more challenging than making one map that stands alone.

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- match the most fitting type of color scheme (e.g., sequential; diverging; qualitative) to specific data sets;

- demonstrate how to identify and specify colors using the three perceptual dimensions of hue, saturation, and lightness;

- integrate knowledge of color perception and human visual limitations (including color-vision impairment) into map color decision-making;

- standardize and classify data appropriately for use on choropleth maps;

- select an appropriate color scheme for a map based on probable perceived connotations of those colors as they relate to the map's data.

Lesson Roadmap

| Action | Assignment | Directions |

|---|---|---|

| To Read | In addition to reading all of the required materials here on the course website, before you begin working through this lesson, please read the following required reading:

Additional (recommended) readings are clearly noted throughout the lesson and can be pursued as your time and interest allow. | The required reading material is available in the Lesson 4 module. |

| To Do |

|

|

Questions?

If you have questions, please feel free to post them to the Lesson 5 Discussion Forum. While you are there, feel free to post your own responses if you, too, are able to help a colleague.

Color Overview

Color Overview mxw142Color is frequently used to symbolize information on maps. In recent years, cartographers have begun to employ color more frequently. in a study of map-color use in scientific journals, White et al., (2017) found that the use of color in published map figures increased from 18.4% in 2004 to 69.9% in 2013. This trend can primarily be attributed to the expansion of practical map production technologies. The cost of color printing, for example, is no longer prohibitory. Additionally, the increasing popularity of web-based dissemination of maps and other visual graphics makes such color production costs irrelevant. Tools such as ColorBrewer Colorbox, and Colorgorical have also made color selection easier; the first of these is now integrated into the color selection tools in ArcGIS Pro and a separate package in R (RColorBrewer).

In this lesson, we will explore the basics of specifying, mixing, and selecting colors for choropleth maps. You should aim to understand and properly apply the color schemes available in GIS software, and alter them as appropriate based on your maps’ audience, medium, and purpose. Eventually, you might even design your own color schemes from scratch.

You may remember the map in Figure 5.1.2 from Lesson 1. This map is a thematic map, and more specifically, a choropleth map. Discussions of color in mapping often focus on choropleth maps. This is for good reason—choropleth mapping is the most common thematic mapping technique, and its employment typically requires thoughtful analytical use of color. We will discuss the details of choropleth mapping later in this lesson. However, note that color is also frequently used on other types of maps. General purpose maps often employ color to delineate between different kinds of features, and maps that focus on other symbolization types (e.g., proportional symbol maps) often also use color to encode an additional variable, or to add visual interest.

Recommended Reading

Harrower, Mark, and Cynthia A. Brewer. 2003. “ColorBrewer.Org: An Online Tool for Selecting Colour Schemes for Maps.” The Cartographic Journal 40 (1): 27–37. doi:10.1002/9780470979587.ch34.

Gramazio, Connor C., David H. Laidlaw, and Karen B. Schloss. 2017. “Colorgorical: Creating Discriminable and Preferable Color Palettes for Information Visualization.” IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 23 (1): 521–530. doi:10.1109/TVCG.2016.2598918.

White, Travis M., Terry A. Slocum, and Dave McDermott. 2017. “Trends and Issues in the Use of Quantitative Color Schemes in Refereed Journals.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 4452 (April): 1–20. doi:10.1080/24694452.2017.1293503.

Specifying Colors

Specifying Colors mxw142When you hear the word "color," words such as blue, red, and green likely spring to mind. Though these are colors in the colloquial sense, these are better described as color hues. Color has more dimensionality than just the color name. In fact, when thinking about color as a visual variable, each color is specified not just by hue but by three dimensions: hue, lightness (also “brightness” or “value”), and saturation (also “chroma” or “intensity”) (Figure 5.2.1). Some people regard these “alternative terms” as completely synonymous with each other, while others argue that they each refer to something specific. For now, just know that the synonymous terms refer to roughly the same properties.

Color is produced when light is either reflected off of (e.g., a car; a printed map) or emitted by (e.g., a computer screen) an object. Hue refers to the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum where human vision is sensitive. We can discuss color falling along that spectrum in terms of its wavelength of light, from longest (oranges and reds), to shortest (blues and violets). Figure 5.2.2 shows nine swatches of color with different hues, in the order of the rainbow spectrum. It is important to understand that the electromagnetic spectrum offers a vast range of wavelengths, and the human visual system can only perceive a relative tiny portion of that range. For an overview of the electromagnetic spectrum, NASA has a useful website (https://science.nasa.gov/ems/01_intro/).

In mapping contexts, hue is typically used to differentiate between features. In general purpose maps, for example, the use of different hues creates different categories, and helps the reader identify different features as belonging to a particular group. In Figure 5.2.3, for example, the color choices are visually distinguishable, and improves the legibility and aesthetics of the map. Though multiple types of roads are shown, all roads are shown in red. Similarly, all hydrologic features and labels are shown in blue - a familiar color easily recognizable by map readers as associated with water. Furthermore, features and their labels that are shown in green, map readers conceptually associate with vegetation.

Lightness is another dimension of color; it describes how perceptually close a color appears to a pure white object. Lightness is also commonly called value, though cartographers sometimes avoid that term, as value is also used to describe data values—using the same word for both items can cause confusion. Another alternative word, brightness, might sound like you’re referring to the brightness of a screen on which a map is being displayed, so use of that word is not recommended either. Lightness works well for visually encoding the order and/or magnitude of thematic data values—typically, lighter colors signify lower data values (i.e., less implies less), and darker, more visually-prominent features implies higher data values.

The third dimension of color is saturation. Saturation is also sometimes called chroma or intensity. Highly saturated colors are particularly useful for calling attention to small but important map elements that would otherwise be lost (Figure 5.2.4). Caution should be used when using saturation in this way, however—the use of too many highly saturated colors, particularly over large areas, may be distracting or accidentally overemphasize unintended features. An effective alternative approach is to desaturate your basemap/background so that your most important features can remain at a reasonable saturation level, but still stand out. If you look at maps in popular media outlets, such as the New York Times or National Geographic, you’ll notice that this approach is extremely common.

The three color dimensions (hue; lightness; saturation) were originally identified by Dr. Albert H. Munsell in the early 20th century. Munsell’s first color model, a color sphere, was an attempt to fit these three dimensions of color into a regular shape. Though this model was still a breakthrough, Munsell realized that it was quite insufficient, as human color perception is not linear and cannot be accurately modeled by a regular shape. The final shape he landed on looks more like a lopsided ellipsoid. The Podcast 99% Invisible has written an excellent short piece on the origins and specifics of the Munsell's color system, with helpful explanatory graphics. Read it here: The Color Sphere: A Professor's Pivotal "Color Space" Numbering System.

Figure 5.2.5 below takes a top-down approach to visualizing this color space: each of the four graphics demonstrates what is, in essence, a slice of the Munsell model, with increasing lightness from left to right. As shown, the colors that the human eye can perceive do not change linearly through color space—note that there is a greater range of red hues than blue hues. This non-linearity makes color specification and design a challenging task.

Student Reflection

Imagine you want to create a categorical map with a large variety of colors. What does Munsell’s model suggest about the kind of colors that would be best used for this purpose?

Though Munsell’s model is helpful for understanding color perception, and perhaps for sharing color specifications with others, a working knowledge of other models is required for building color schemes in GIS and graphic design software. When specifying colors, it is important to consider the display medium that you are using to create them. When mixing paint, cyan, magenta, yellow, and black are used (CMYK [“K” stands for black because it used to refer to the “key plate” in printing and that mixing CMY does not produce a true black, which had the most detail and was usually black]). As mixing paint (or laser printing toner) results in less light being reflected from the color surface, this is called subtractive mixing. The opposite occurs on digital display screens, which create colors by mixing red, blue, and green (RGB) light. Mixing these primaries is called additive mixing.

ArcGIS offers a wide selection of color model choices for specifying colors, including RGB, HSV, and CMYK. RGB and CMYK color models refer to the aforementioned models for mixing additive and subtractive primaries, respectively. RGB is useful for digital media, and CMYK is the color language typically used by graphic artists, largely for print media. Another popular model is hue, saturation, and value (HSV). HSV is reminiscent of the Munsell model (see Figure 5.2.8), but with much greater symmetry—recall the oddly-shaped structure of Munsell’s model.

The symmetry of HSV makes it fit much better into the language of computers, but as human color perception is not linear (recall Figure 5.2.5), using HSV can cause problems unless you remain cognizant of this shortcoming.

Additional color models, including hue, saturation, and lightness (HSL) and Commission internationale de l'éclairage that expresses color as three values: L* (perceptual lightness) and a* and b* (red, green, blue and yellow) (CIEL*a*b* or CIELAB), offer other ways of specifying colors. We will not go further into the details of color specification here, but you are encouraged to explore the recommended readings for more information.

Recommended Reading

Chapter 7: Color Basics. Brewer, Cynthia A. 2015. Designing Better Maps: A Guide for GIS Users. Second. Redlands: Esri Press.

Types of Color Schemes

Types of Color Schemes mxw142Types of color schemes

When applying color schemes to maps, there are many factors to consider. First and foremost, keep this rule in mind: the perceptual structure of the color scheme should match the perceptual structure of the data. For example, if your data go from high to low (sequential data), you should use a color scheme that demonstrates this quantitative order, as shown in the map in Figure 5.3.1. Note also that the primary color hue, green, was selected due to its cultural association with the mapped theme.

There are three main types of color schemes: sequential, diverging, and qualitative. We will discuss what these mean below, but you may find it helpful to augment our discussion by visiting ColorBrewer, a popular tool for choosing color schemes on maps. This tool was designed by Dr. Cynthia A. Brewer at Penn State. ColorBrewer’s interface is shown in Figure 5.3.2. Feel free to explore the many color schemes available on the site as you read more about types of color schemes in this lesson and consider how you might apply them to your maps.

Sequential color schemes are one of the most popular color schemes used in thematic mapping, as they intuitively communicate the quantitative order of data values. If you are attempting to visually contrast the numerical arrangement of values of a particular dataset, then a sequential color scheme is probably an appropriate choice. Several examples of sequential color schemes are shown in Figure 5.3.3.

Though color lightness is effective on its own, sequential color schemes are also often designed with multiple harmonious hues, such as in the color schemes shown in Figure 5.3.4. The multi-hued nature of these color schemes can make it easier for viewers to discriminate between all data classes on the map. They also often create more aesthetically-pleasing visualizations. As long as it doesn't take away from readers' comprehension of your data, why not make a better-looking map?

As shown in Figure 5.3.5, when hue is paired with lightness it can create dramatic contrast in a sequential color scheme. When adding sequential color schemes to such maps, ensure that the chosen scheme accurately reflects the progression of your data—it is challenging to create an effective sequential color scheme that relies heavily on hue.

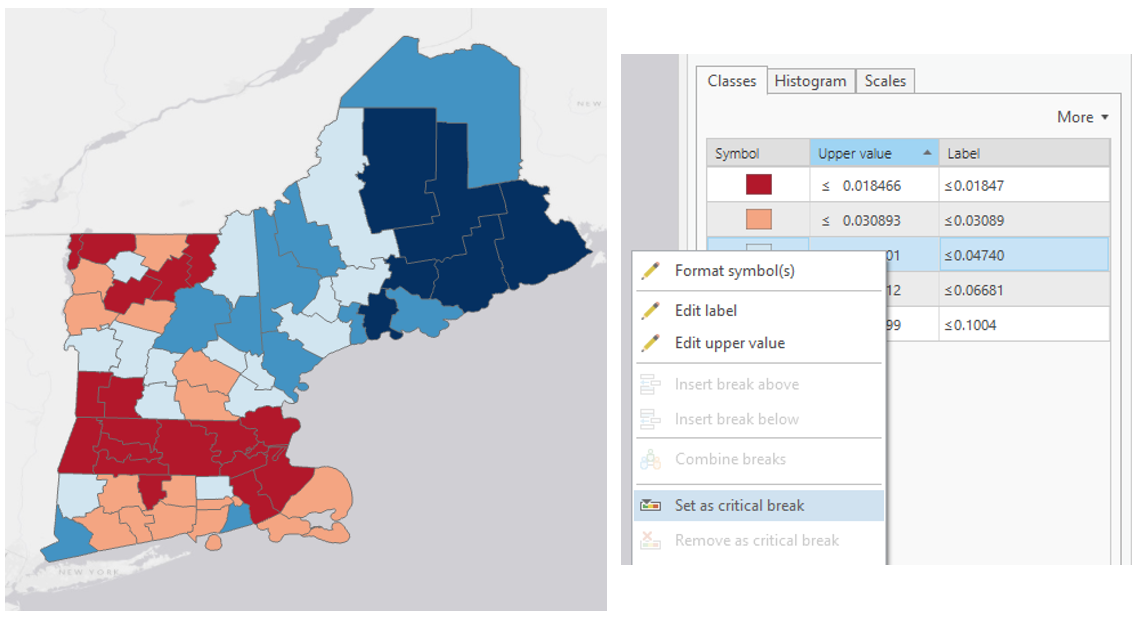

Diverging color schemes are similar to sequential color schemes, as they also demonstrate order. However, instead of showing a single progression, they visualize the distance of all values from a meaningful midpoint, usually an average or median using two contrasting color hues. For example, a map that shows percent change with red hues showing increases and blue hues showing decreases. This middle value or class is often represented using white or a light grey representing a neutral position in the data. Diverging schemes are typically limited to two color hues. Using a third color hue may cause readers to assume that the color scheme is qualitative (more on that later).

If your data has a natural midpoint—such as a 0% change in some phenomenon— a diverging color scheme works well, as it permits the reader to easily identify values on the map as either above or below that value. An example of this is shown in Figure 5.3.7 below.

Other values can also serve as helpful midpoints in mapped data. For example, a map might use a diverging color scheme to demonstrate values that fall above or below the data’s mean, or perhaps some external value (e.g., a choropleth map of median income where a diverging color scheme is centered around a calculated national level value of a living wage).

An important consideration when applying a diverging color scheme is whether your data has a critical class or a critical break (Figure 5.3.8). Using a diverging scheme with a critical class will highlight a critical group of areas on your map, as well as those above and below. A critical break will show all areas as either above or below a critical value—there is no “neutral” color class in this scheme. Diverging schemes also do not always have to be symmetrical. Your critical class/break will often be near the center of your data range, but it in no way needs to be.

Keep the divergent schemes shown in Figure 5.3.8 below in mind as we discuss data classification for choropleth mapping later in the lesson.

Student Reflection

View the map in Figure 5.3.9 below. Why is a diverging color scheme used here? What does the map tell you? What doesn’t it tell you? Would you design it differently?

The third type of color scheme is the qualitative color scheme. These schemes are used to demonstrate differences—but not numerical order—between map features. Several examples are shown in Figure 5.3.10 below.

Qualitative color schemes are often used when creating maps of political boundaries, or to create categorical choropleth maps, such as the one in Figure 5.3.11. As the term choropleth is composed of the Greek words for “area/region” (khṓra) and “multitude” (plēthos), it is technically incorrect to refer to a map of nominal values as a choropleth map, despite the characteristic enumeration-unit shading such maps employ. These maps should instead be called chorochromatic maps. That being said, it’s unlikely that you’ll hear even GIS or most cartographer professionals use that term. But hey, be the change you wish to see in the world, right?

Perhaps the most common use of qualitative color schemes in mapping is in land use/land cover (LULC) maps. These maps seek to demonstrate category (e.g., residential vs. commercial) but not to demonstrate order. An example of a land cover map is shown in Figure 5.3.12.

The (color vision unimpaired) human eye can discriminate between about twelve different hues in the same image, and, dependent on the reader and the design of the map, often even less. Many maps, and LULC maps in particular, contain more than this number of categories. A frequent strategy is to group categories into hue classes (e.g., green for vegetation) and then to use lightness and saturation to create intra-class differences. In Figure 5.3.12, for example, green hue is used for forest, and lightness variations are used to differentiate between forest types. When designing a color scheme for land classification-land cover maps, one must be careful to choose color variations that are visually perceptible from others (i.e., too many similar green hues may not be visually perceptual).

Student Reflection

View the categories of land cover in Figure 5.3.12. Does the perceptual structure of the data match the perceptual structure of the colors assigned? Does it do so in more ways than one?

Recommended Reading

Chapter 8: Color on Maps. Brewer, Cynthia A. 2015. Designing Better Maps: A Guide for GIS Users. Second. Redlands: Esri Press.

Chapter 14: Choropleth Maps. Slocum, Terry A., Robert B. McMaster, Fritz C. Kessler, and Hugh H. Howard. 2009. Thematic Cartography and Geovisualization. Edited by Keith C. Clarke. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Visual Perception Constraints

Visual Perception Constraints mxw142So far in this lesson, we have talked about multiple ways to specify colors, and how we might apply them to maps. As we discuss color, however, we also need to discuss color vision deficiency—the inability to discriminate between certain (or occasionally, all) colors. Though color blindness varies by gender and ethnicity, you can generally expect that between five and ten percent of your map readers will have some form of color deficiency. You may even have some form of color vision deficiency yourself.

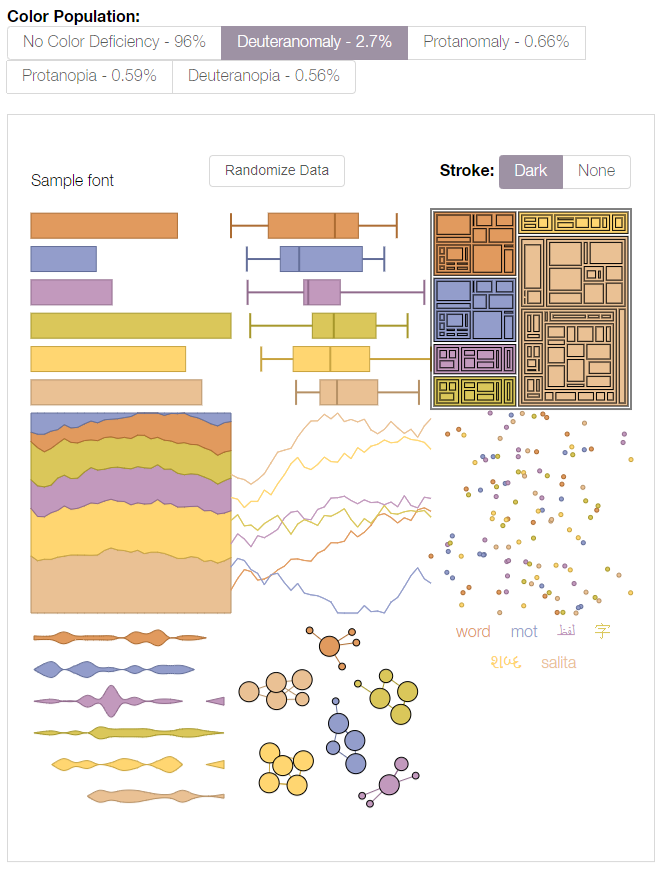

The good news is that several web tools exist to help you design more accessible maps. Viz Palette, developed by Elijah Meeks and Susie Lu, is one useful example. It permits you to import your own color schemes from popular color-picking tools such as ColorBrewer and view their appearance through the eyes of those with different types of color vision deficiencies. Vizcheck is an application that allows an image or map to be uploaded and view how the colors on that image or map appear according to different color vision impairments.

Tools such as Viz Palette are useful for understanding how different people might view your data visualizations and maps. You can then decide for yourself whether your chosen palette is acceptable. ColorBrewer also lets you select from among only color schemes that have been empirically-verified as colorblind friendly its interface includes an option to show only “colorblind safe” color schemes. Unsurprisingly, the scheme in Figure 5.4.1(2) does not appear.

How much you factor color accessibility into your map design will depend greatly on its audience, medium, and purpose. Color discriminability is affected by many factors outside of genetics, including reader age, lighting conditions, and map resolution. It is also more crucial in some mapping contexts than in others. A map for entertainment, for example, may sacrifice accessibility for increased aesthetics and visual interest among the not color-vision impaired. When a map’s purpose is emergency management or vehicle routing, however, the cartographer may place a greater value on ensuring readability for all map users.

Even among those without color vision impairments, human color perception does not come without flaws. View the squares labeled A and B in Figure 5.4.3—do they look the same to you?

You likely perceive squares A and B as different shades of grey, but, as you may have guessed, your eyes are deceiving you—these two squares are exactly the same shade of grey. (If you don't believe it, check out the interactive version of this graphic at illusionsindex.org). This is the result of a principle of color interpretation called simultaneous contrast, or induction—colors appear differently, dependent on the backdrop against which they appear.

Student Reflection

View the maps in Figure 5.4.4: which colors in the second map (1, 2, 3, 4) do you think match the colors in areas A and B?

Student Reflection Answer

The color in A matches the color in 4; the color in area B matches area 2. Is this what you were expecting?

To date, little empirical research in cartography has evaluated the influence of induction on map interpretation, and, thus, few suggestions exist for minimizing its effects in practice. You should, however, anticipate the effects that varied backgrounds will have on the interpretation of your map symbol colors, particularly for maps in which such comparisons are common and/or critical.

So far in this lesson, many of our examples have been choropleth maps—the most common thematic mapping technique, and one which typically makes extensive use of color as a visual variable. In the next section, we will focus on other aspects of choropleth mapping, including data standardization and classification, as a deeper understanding of how these maps are built using data is required for selecting an effective color scheme.

Recommended Reading

Chapter 8: Color on Maps. Brewer, Cynthia A. 2015. Designing Better Maps: A Guide for GIS Users. Second. Redlands: Esri Press. Bach, M. (n.d.).

Data Standardization

Data Standardization mxw142The choropleth mapping technique should be used on standardized data such as rates and percentages—rather than on totals or counts—which are better represented by point symbol maps.

There is almost never a good reason to make a choropleth map without standardizing your data. Why? Because if you don’t standardize your data, then you are inadvertently creating a map of the underlying population. For example, you could create a choropleth map of the United States showing counts of, say, gas stations in each state. Texas and California have the largest populations of any state in the US, so they would likely have more gas stations and show primacy in this count. The result is a map without much useful information—California and Texas have more people and things because simply because they have more people and things. The map would tell us nothing interesting about each state’s respective consumption of gas or transportation infrastructure in relation to the underlying population. However, if you were to map gas stations per capita (i.e., if you standardized your data), then we would be able to meaningfully compare rates, and a choropleth map would be an appropriate method.

If you’re lucky (really, really lucky), your data will be delivered in the proper standardized format. For example, for each enumeration unit in your data, you might have a rate, density, or index value. All of these are appropriate standardized data for choropleth mapping. Oftentimes, however, you will need to calculate these values yourself. Data from the US Census, for example, is often delivered as count data by enumeration unit but includes a population field which can be used for standardization.

Using the example data in Figure 5.5.1 above, imagine we wanted to map the number of people in each county who are under 18 years old AND have one type of health insurance coverage (Column F). And imagine we created a county-level choropleth map using those Column F values. What would this map tell us? It might tell us a little something about geographic health insurance trends in North Carolina, but mostly it would just show us in which counties more people live.

Remember the importance of map purpose: rather than just making a population map, we want to understand the geography of health insurance coverage for young people. For this, we need to map standardized values. To do so, we can divide the number of under 18-year-olds with one type of health insurance (Column F) by the appropriate universe: the count of items (here, people) that could possibly fall into this category. Since our data value of interest only applies to a specific age group, our universe, in this case, is not all people (Column D), but all people under 18 (Column E).

Some texts and software programs, including ArcGIS, call this process normalization rather than standardization. As suggested by (Slocum et al. 2009) we use the term standardization, as normalization has a more specific meaning in statistics with which we do not want this process to be confused.

Making Choropleth Maps

Making Choropleth Maps mxw142

Let’s return again to a map that should be becoming familiar, posted now as Figure 5.6.1. Median income is visually encoded in each state as belonging to one of four classes: (1) less than $45,000; (2) $45,000 to $49,999; (3) $50,000 to $59,999, and (4) $60,0000 and more. How were these classes chosen?

Student Reflection

One side-step before we discuss data classification: think back to our discussion of types of color schemes— can you think of another type of color scheme that would be effective in Figure 5.6.1? Do you think it would be better?

When the map in Figure 5.6.1 was being designed, the aforementioned classes had to be decided upon – and there are many different ways in which class breaks in median income could have been drawn. So, how do you choose? Rather than simply choosing the default classification scheme that your GIS software suggests, you should think critically about how your data classes are defined. Before you decide how to class your data, the first decision you should make, however, is not how, but whether to class your data.

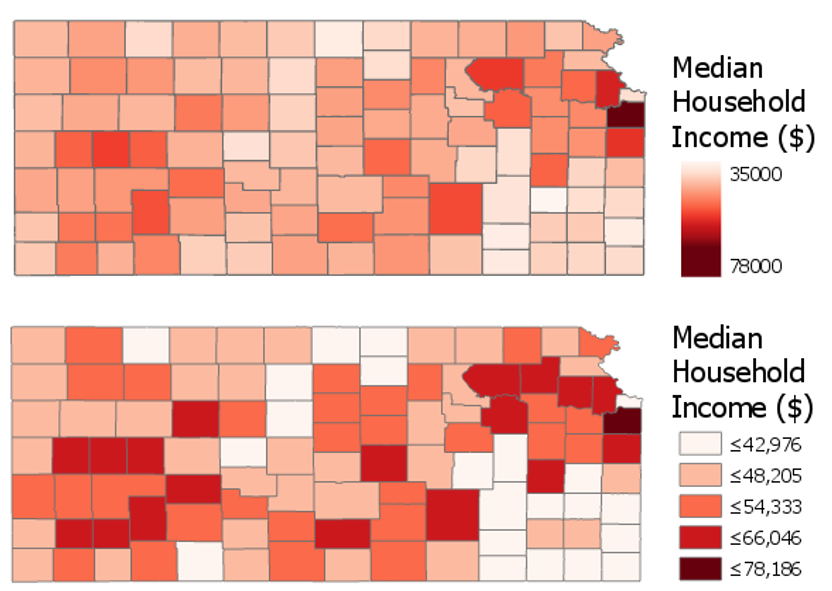

Figure 5.6.2 shows an example of two maps—one unclassed and one classed. Unclassed maps (sometimes called N-classed, where the N represents the number of enumeration units, or "class-less" map) encode color (usually with lightness) based on the specific value within each enumeration unit, rather than based on a pre-defined class within which the data value falls. These maps are useful as—if designed properly—they may more accurately reflect the ordinal nuances in the distribution of the data as map readers can see the differences between the color lightness (a given color lightness is more or less light than its neighbors). However, unclassed maps should not be considered an easy solution to the problem of data classification. They have their own disadvantages, for example, they make it challenging for the reader to match the value encoded in an enumeration unit to its location on the legend.

Before modern GIS software, unclassed maps were quite difficult to create, but new technology has made their design quite simple. Unclassed maps show a visualization of the data that respects the inherent numeric distribution of data values, while classifying maps gives you more control over the final map. It will be up to you as the map designer to decide whether to class your map; however, many map readers—and cartographers—still prefer classed maps.

As you will likely be classifying your maps, it is important to understand how this process can influence your final map design. Most of the commonly-used classification methods are available in ArcGIS, and the software interface gives a simple explanation of each of these methods (Figure 5.6.3). We will not discuss the mathematical details of each of these classification methods here—it is recommended that you explore the recommended readings or do your own research on the web to learn more.

Natural Breaks (Jenks): Numerical values of ranked data are examined to account for non-uniform distributions, giving an unequal class width with varying frequency of observations per class.

Quantile: Distributes the observations equally across the class interval, giving unequal class width but the same frequency of observations per class.

Equal Interval: The data range of each class is held constant, giving an equal class width with varying frequency of observations per class.

Defined Interval: Specify an interval size to define equal class widths with varying frequency of observations per class.

Manual Interval: Create class breaks manually or modify one of the present classification methods appropriate for your data.

Geometric Interval: Mathematically defined class widths based on a geometric series, giving an approximately equal class width and consistent frequency of observations per class.

Standard Deviation: For normally distributed data, class widths are defined using standard deviations from the mean of the data array, giving an equal class width and varying frequency of observations per class.

Though Figure 5.6.3 gives brief descriptions of each classification method, it offers little advice as to when to use them. A good way to approach this question is to view your data along the number line. You can use histograms (for large data sets) or dot plots (for small data sets) to visualize how your data is distributed, and to select class breaks accordingly. The following suggestions are given by Penn State cartographer Dr. Cynthia Brewer.

- For data with near-normal distributions, consider classifying your data based on the mean and standard deviation.

- For skewed distributions, consider systematically increasing classes, such as arithmetic and geometric classing methods.

- If your data are evenly distributed, equal interval and quantile classing methods work well. These methods are also best for ranked data.

- Natural breaks, created using Jenks classing method or in selecting breaks by eye, work best for data that shows obvious groupings through the range. The natural breaks method highlights the numeric relationships in the data values.

We will look at data using dot plots during this lab associated with this lesson. When you make maps, unless you are working with a very large data set, this will often be the most effective way to visually investigate the distribution of your dataset in order to choose a classification method or visually/manually place your own breaks. ArcGIS, however, creates histograms of your data that you can also use to understand how the breaks you have chosen to relate to the spread of your data.

Student Reflection

Compare the breaks, histograms, and maps in Figure 5.6.4 below. Which classification method would you have chosen? Why?

![comparison of two maps (top map created using quantiles classification method, bottom map using natural breaks [Jenks]), see surrounding text](/geog486/sites/geog486/files/Lesson_04/Images/4.5.10.PNG)

Note that the spread of your data is only one of multiple elements you should consider when choosing how to classify your data. As with other map design choices, your map's intended audience, medium, and purpose are also of vital importance here.

In addition to choosing a classification method for your maps, you also must decide how many classes to create. It may be tempting to create a large number of classes, as more classes means less simplification of your data, and thus more information conveyed to the map viewer. Unfortunately, the human eye can only differentiate between so many colors. There are recommendations for the maximum number of color classes on a map, generally ranging from about 5 to 12. But a good rule of thumb is that the fewer classes your reader has to remember, the better.

Student Reflection

View the maps in Figure 5.6.5 below. Looking at the map on the left, can you identify within which class county x belongs? How confident are you that this is the correct answer? What about in the map on the right?

Finally, when classifying your map data, you will have to contend with outliers in your dataset. Consider a county-level map, where one county has double the rate (for example, of people with graduate-level degrees) of any other county in your data. Some classification methods, such as natural breaks or equal intervals, will most likely group this outlier into a class of its own. Other methods, such as quartiles, will simply place it into a group with all the next-highest counties.

There is no rule for which method is best, except that context matters. Is the rate high because that county contains the most prestigious university in the state? In that case, you probably want it to be highlighted on your map. If, instead, it is the highest because only five people live there—and two are college professors—you probably don’t. In general, the more data you have, the less likely an outlier is to be noise: this is called the law of large numbers. Whenever possible, however, you should investigate the possible causes of an outlier; there is no substitute for contextual clues.

There are additional ways to classify your data, including by combining methods; for example, using equal intervals for most of the range, and then switching to natural breaks. Methods also exist that consider not just the distribution of data along the number line, but its distribution through geographic space as well. These are beyond the scope and intent of this lesson, but be aware that you may encounter them in the future.

Recommended Reading

Chapter 4: Data Classification. Slocum, Terry A., Robert B. McMaster, Fritz C. Kessler, and Hugh H. Howard. 2009. Thematic Cartography and Geovisualization. Edited by Keith C. Clarke. 3rd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Chapter 11: Data Maps: A Thicket of Thorny Choices. Monmonier, Mark. 2018. How to Lie with Maps. 3rd ed. The University of Chicago Press. (this week's required reading - it relates especially well to this topic).

Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. 1971. “Belief in the Law of Small Numbers.” Psychological Bulletin 76 (2): 105–110.

Making Sense of Maps

Making Sense of Maps mxw142By now, you should feel pretty good about creating a single choropleth map. But while we frequently encounter choropleth maps in the singular, the power of maps often comes from our ability to compare them. Static maps—all of the maps we’ve discussed thus far—typically only represent one snapshot in time. What if we are interested in how a phenomenon has changed over time, or how it varies between two disparate locations?

View the two maps below in Figure 5.7.1. They are both maps of population density from New Jersey and Vermont and are shown using the same scale. A casual inspection of the maps (to non-US residents, perhaps), the vibrant colors appearing on the Vermont map suggest that this state may have a higher level of population density. But take a closer look at the legends.

The legends in the maps in Figure 5.7.1 don’t match. The darkest color, for example, represents a vastly higher level of population between the two maps. How much does population density differ between New Jersey and Vermont? Due to the unmatched legends, it’s almost impossible to tell.

Using the same data classification scheme for a set of maps whose purpose is to compare a dataset is necessary. For example, the maps in Figure 5.7.2 use the same data, but this time, both legends are equivalent.

This gives us an entirely different view of the data: New Jersey is now represented as obviously more densely populated. Note, however, that this map just took New Jersey’s classification scheme and applied it to Vermont, which is still not a good solution. Though it is now easy to compare these states, we are unable to discern which areas of Vermont are more populated than others: they are all simply classified as "less than 562 residents per square mile." Making maps that work well both independently and when compared is a challenging task, and one which we will contend with in Lab 5.

Another important aspect of choropleth—and any—map design is making sure that marginal elements such as legends and labels are well-crafted to support reader comprehension of your map. For example, see Figure 5.7.3. It may seem at first that this legend is too text-heavy at the expense of the geography mapped: you don’t generally create visual graphics with the intention of asking people to read. However, without necessary information being conveyed through the text, the content of the map would be confusing, and many readers would likely misinterpret it.

This map also purposefully places breaks in the data; for example, one break is placed at 24 percent, which is the percentage of all people in the US who are under 18 years old. The break is annotated to inform the reader of this fact; without this annotation, the use of this specific break would not be useful. Additional legend annotations (e.g., “High proportion of AIAN are young”) serve to clarify the map.

Figure 5.7.4 below similarly uses a text explanation to clarify the data mapped. Due to the classification scheme used, the location indicated by the leader line and Prisons* note does not immediately stand out as an outlier. However, given the topic of the map, this explanation is important. We discussed dealing with outliers earlier in the lesson—one option for dealing with a relevant outlier is simply to point it out to your readers via explanatory text. Mapping is all about graphic presentation, but sometimes the best solution is a simple, concise, text explanation.

Recommended Reading

Chapter 3: Explaining Maps. Brewer, Cynthia A. 2015. Designing Better Maps: A Guide for GIS Users. Second. Redlands: Esri Press.

Chapter 5: Color: Attraction and Distraction. Monmonier, Mark. 2018. How to Lie with Maps. The University of Chicago Press.

Color and Data

Color and Data mxw142When using color as a symbol on your maps, your first priority should be to apply it analytically. As stated before: the perceptual structure of your color scheme should match the perceptual structure of your data. You should apply color based on the guidelines previously discussed in this lesson before worrying about choosing aesthetically-pleasing colors, or your audiences’ likely favorite colors, or colors that correspond to the context of the data (e.g., using a green color scheme to create a map about sustainability).

However—when appropriate—adding context to colors in your maps can benefit your readers. See the map in Figure 5.8.1 below. Rather than choosing a traditional sequential color scheme, this cartographer chose to match the map’s colors to colors of tree leaves as they turn in autumn.

This approach may not always work to best represent the mathematical order of your data classes. But your maps aren’t always about dots along a number line—they represent real-world phenomena. Using color assignments that make sense (e.g., red for negative values), or are customary (e.g., yellow for residential in zoning maps) can improve the clarity and comprehensibility of your maps.

Recommended Reading

Lin, Sharon, and Jeffrey Heer. 2014. “The Right Colors Make Data Easier to Read.” Harvard Business Publishing.

Bartram, Lyn, Abhisekh Patra, and Maureen Stone. 2017. “Affective Color in Visualization.” CHI Proceeding: 1364–1374. doi:10.1145/3025453.3026041.

Critique #3

Critique #3 eab14Critique #3 will be your second critique involving a peer review of a map created by someone in this class. In this activity, you will be assigned a colleague's map from this class to critique from Lab 4: Terrain Mapping.

Your peer review assignment includes writing up a 300+ word critique of one of your colleague's Lesson 4 Lab.

In your written critique please describe:

- three (3) things about the map design that you think works well and why.

- three (3) suggestions you have for improvement of the map design and why these improvements would be helpful.

According to the two prompts above, a map critique is not just about finding problems, but about reflecting on a map in an overall context. Your critique should focus on the map design that works well as much as it does on suggestions for design improvements. In your discussion, you should connect your ideas back to what we learned in the previous lessons.

Remember, your critique should be as much about reflecting upon design ideas well-done as it is about suggesting improvements to the design. In your discussion, connect your ideas to concepts from previous lessons where relevant.

Grading Criteria

Registered students can view a rubric for this assignment in Canvas.

Submission Instructions

You will work on Critique #3 during Lesson 5 and submit it at the end of Lesson 5.

Step 1: When a peer review has been assigned, you will see a notification appear in your Canvas Dashboard To Do sidebar or Activity Stream. Upon notification of the Peer Review (Critique), go to Lesson 4: Lab 4 Assignment. You will see your assignment to peer review. (Note: You will be notified that you have a peer review in the Recent Activity Stream and the To-Do list. Once peer reviews are assigned, you will also be notified via email.)

Step 2: Download/view your colleague's completed map.

Step 3:

- Write up your critique using the prompts above in a Word document.

- Please write the student name of the map that you have been assigned to critique at the top of the page.

- Be sure to review the critique rubric in which you will be graded for more guidance on the expected content and format of your review.

- Save your Word document as a PDF.

- When submitting your PDF, use the naming convention outlined here:

YourLastName_LastNameOfColleagueCritiqued_C3.pdf

Step 4: In order to complete the Peer Review/Critique, you must

- Add the PDF as an attachment in the comment sidebar in the assignment.

- Include a comment such as "here is my critique" in the comment area.

- PLEASE DO NOT complete the lesson rubric as your review, award points, or grade the map you are critiquing. Even though Canvas asks you to complete the rubric, PLEASE DO NOT COMPLETE THE RUBRIC OR ASSIGN POINTS/GRADE.

Step 5: When you're finished, click the Save Comment button. Canvas may not instantly show that your PDF was uploaded. You may need to exit from the course, leave the page, refresh your browser, or some combination thereof to see that you've completed the required steps for the peer review. If in doubt, you can send a message to the instructor for them to check an confirm that your PDF was successfully uploaded.

Note: Again, you will not submit anything for a letter grade or provide comments in the lesson rubric..

Lesson 5 Lab

Lesson 5 Lab mxw142Color and Choropleth Mapping in Series

In Lab 5, we will explore different ways of choosing data classification and color schemes for choropleth maps. As a cartographer, you will often have to choose between several of these options, many of which may seem at first glance to be equally appropriate. In this lab, we will utilize data from the American Community Survey, provided by the U.S. Census—a commonly used source of data for statistical maps. From this data source, we will focus on a specific variable frequently in focus during public policy debates: health insurance.

The first part of Lab 5 will focus on data classification. There are many ways to classify statistical data on maps, and it is important that you understand them, and be able to defend your choice of classification scheme to others. As we will be not only be classifying data but also adding that data to maps, this lab will also focus on the use of color on maps. Finally, as suggested in the lesson content, we will explore ways of making comparable maps - in this lab, we will be making three pairs of maps.

Lab Objectives

- Create three pairs of county-level choropleth maps describing health insurance in New England.

- Utilize shared or similar legends to help readers understand the relationships between pairs of maps.

- Use information about data distributions and health insurance rates in New England and the US overall to plan shared data classification breaks.

- Understand the impact of different color schemes and classification methods; be able to reflect upon and write about these decisions.

Overall Lab Requirements

For Lab 5, you will create three pairs of maps, each pair as its own full-page map layout. In total, you will have three separate pages. Two maps will appear on each page. You will also write a short reflection statement about each pair of maps.

- For each pair, use the same map positioning and scale within each frame; one scale bar for both maps.

- Prepare balanced page layouts with all elements suitably sized and balanced negative space—no pinched elements or visual collisions.

- Attend to text hierarchy: overall title, subtitles, legend title(s), legend class labels, scale, data source, and name. Use thoughtful and efficient wording when labeling map elements.

Map Requirements

Map Pair One: Use a Sequential Color Scheme

- Choose two related variables to map from the provided American Community Survey (ACS) data.

- Do not just choose two age groups (e.g., 18-under; 19-25 years).

- The mapped data must be two related variables.

- Select class breaks manually

- Create dot plots in Microsoft Excel

- Draw appropriate breaks using your eye to judge the data

- Enter these values as manual breaks in ArcGIS Pro.

- Use a sequential color scheme and a single shared legend for both maps.

- Include a short write-up (100+ words) which includes a screenshot of your dot plot with lines drawn to demonstrate the breaks you chose, as well as a short description of how you selected these breaks. Also, include a screenshot of the symbology pane for both maps.

Map Pair Two: Use a Diverging Color Scheme

- Re-create your maps from map pair #1; using a diverging color scheme.

- Choose a critical break or class using external information using either of the approaches listed

- Use a value that is directly derived from your chosen data set (e.g., the mean of the data)

- Any logical dividing point that is calculated from an external source (e.g., the U.S. national average)

- Adjust other class breaks accordingly.

- Use a single well-designed shared legend for both maps.

- Include a short write-up (100+ words) describing the critical break or class you chose and why. You may also discuss why you selected this particular color scheme.

Map Pair Three: Unclassed vs. Classed Maps (Choose your own appropriate color scheme)

- Choose one of the maps from map pairs #1 and #2 and create two more maps of this data—unlike in the previous layouts you made, these two maps will show the same data/topic.

- One of the maps should be an unclassed map; one should be classed.

- For the classed map, choose a classification method available in ArcGIS Pro—do not manually adjust the class breaks created, but ensure that this method is appropriate for the data you are mapping.

- Include a well-designed legend for each map.

- Include a short write-up (100+ words) that describes why you chose the classification method you did, and how you think its effectiveness compares to that of the unclassed map.

Lab Instructions

- Download the Lab 5 zipped file (43.2 MB). It contains:

- a project (.aprx) file to be opened in ArcGIS Pro;

- a database that includes the spatial boundary and health insurance data needed to start this lab;

- a spreadsheet containing New England health insurance data.

- Data source: US Census Bureau - TIGER boundary files and American Community Survey (ACS) S2701 (Health Insurance Coverage Status) 5-year estimates for 2016.

- For the purposes of this lab, New England is defined as the following states: Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine.

- Extract the zipped folder, and double-click the blue (.aprx) file to open ArcGIS Pro.

- In addition to the ArcGIS Pro file, you will also be using the ACS_2016_NewEngland_HealthInsurance.xlsx file to explore New England health insurance data.

- Note that you will not need to import any data into ArcGIS Pro - all data is included and ready to map. The Excel file is only for visually exploring the data in order to select class breaks for your maps.

Grading Criteria

Registered students can view a rubric for this assignment in Canvas.

Submission Instructions

- You will have three map layout PDFs to submit. Each will contain one map pair using the naming conventions outlined below.

- Map Layout/Pair 1: LastName_Lab5_Layout1.pdf

- Map Layout/Pair 2: LastName_Lab5_Layout2.pdf

- Map Layout/Pair 3: LastName_Lab5_Layout3.pdf

- Include your write-ups (all three in one document) as a separate PDF.

- Lab Write-up: LastName_Lab5_WriteUp.pdf

- Remember that your write-up should include three 100+ word sections (300+ words in total) - these write-ups should defend your data classification and color scheme selection choices. The write-up for your first pair of maps must also include an image of your dot plot with annotated breaks, and screenshots of the Symbology Pane in ArcGIS Pro for both maps.

- Lab Write-up: LastName_Lab5_WriteUp.pdf

- Submit the three map layout PDFs and one write-up (also PDF) to Lesson 5 Lab for instructor review.

Ready to Begin?

More instructions are available in the Lesson 5 Lab Visual Guide.

Lesson 5 Lab Visual Guide

Lesson 5 Lab Visual Guide mxw142Lesson 5 Lab Visual Guide Index

- Starting File

- Explore the Health Insurance Data in Excel

- Standardize Chosen Data for Visualization

- Create Dot Plots Using your Standardized Data

- Use this Plot to Visually Select Breaks

- Create Maps (1 & 2) Using These Breaks

- Create Maps (3 & 4) Using Diverging Colors

- Create Maps (5 & 6) Unclassed vs. Classed

- Final Deliverables

- Additional Tips

1. Starting File

This is your starting file in ArcGIS Pro. It includes county-level boundary data for the United States. This county-level file has been joined with health insurance data for New England from the American Community Survey (ACS). A state boundaries file is also included – this file is not needed to map the health insurance data, but you may choose to symbolize it to create visible state boundaries on your map.

2. Explore the Health Insurance Data in Excel

Within the health insurance data provided in the Lab 5 zipped folder, find two variables you are interested in and their associated universes. For example, if you were interested in uninsured people under 18, your value and universe would be those shown in Figure 5.2 below. (note: this is one variable, you need to choose two).

3. Standardize Chosen Data for Visualization

Paste the four columns you will need "as values" (see Figure 5.3) into the Chosen Data sheet. (Reminder: use something other than just age for your maps). This will eliminate the clutter of the full dataset, giving you space to calculate standardized values from your data. We will use these standardized values to determine class breaks for our first set of maps.

Once you have your two variables of interest (and their universes) in the Chosen Data sheet, use Excel to calculate a standardized column of data for each of your variables. You want to divide each variable of interest by its universe (recall the Data Standardization section in Lesson 5).

4. Create Dot Plots Using your Standardized Data

Insert a column of 1s and 2s as shown - we will use this to create a dot plot. When you select columns A and B below and insert a scatter plot, this will create a dot plot showing the distribution of your two standardized variables along the number line.

5. Use this Plot to Visually Select Breaks

Draw lines with the "insert shape" tool to illustrate where you will be placing breaks in your data. Annotate your lines if you choose the breaks for a reason other than just eyeing the dot distribution. For example, if you place a break at the national average for a variable, annotated this break with a text box explanation such as "US national average." Ex: “national average."

Note that Figure 5.7 is an example of how to draw lines above your dot plot, but these are not good breaks.

6. Create Maps (1 & 2) Using These Breaks

We will not be importing our excel data into ArcGIS, as I have already loaded the health insurance data into ArcGIS for you. We only needed the Excel file to decide on what breaks to use for our data classification. Instead of importing standardized values, use ArcGIS to standardize your data for you: make sure the variables you choose match the ones you chose earlier!

You will then manually edit your class breaks to match the ones you drew on your dot plot (use your eye to estimate the values). The screenshot in Figure 5.8 (below) is an example of a screenshot from the Symbology Pane. You will submit a screenshot of the Symbology Pane for both maps in layout one, in addition to an image of your dot plot with annotated breaks.

7. Create Maps (3 & 4) Using Diverging Colors

For these maps, you will be setting a critical class break (e.g., based on the mean of the data) and a diverging color scheme. To create your second pair of maps, choose a diverging color scheme. Then, set a deliberate and useful critical class or break. Once the break is set, you should manipulate the other class breaks manually. As a suggestion, for the other class breaks you could start with the manual breaks you chose for your first two maps, but may need to adjust them to work with this new color scheme. Reference the Lesson 5 reading for ideas and advice on how to choose a critical class or break.

8. Create Maps (5 & 6) Unclassed vs. Classed

For the third set of maps, abandon your previously-selected class breaks. In this set of maps, you will compare the visual difference between a classed map and an unclassed map. Use the same sequential color scheme for both maps so they can be adequately compared. You should also use consistent line design, etc., so as to not distract from the primary difference of interest - the classification method used. Unlike with the first two sets of maps, you will not be mapping two different variables for comparison here. You will choose just one of the variables from your previous maps, and visualize this variable on both of maps 5 & 6.

For your classed map, choose any of the methods available in ArcGIS Pro – but have a reason why! You will discuss your reasoning for choosing one of these methods in your write-up for this map pair.

9. Final Deliverables

For this lab you will submit three layouts, each containing a pair of maps. You will also submit a write-up document, with a 100+ word explanation of your design (data classification and color) choices for each map pair. Make sure to also design a neat and useful layout - see Lesson/Lab 2 for layout design advice.

9.1 Example Map Pair #1

Don’t copy this (poor) layout design – use your own knowledge and judgment. Clean up titles, marginal elements, alignments, etc. – use either portrait or landscape, whichever you prefer. Note that elements which refer to both maps (legend; north arrow; scale bar) need only be included once.

Visual Guide Figure 5.13. Example Map Layout #19.2 Example Map Pair #2

Don’t copy this (poor) layout design – use your own knowledge and judgment.

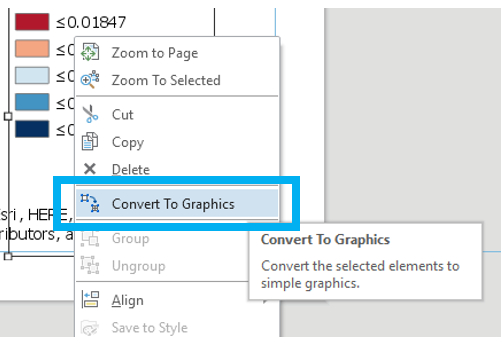

Visual Guide Figure 5.14. Example Map Layout #2Use convert to graphics to manually improve your legend. Use a text box to annotate your critical class/break!

Visual Guide Figure 5.15. Using the Convert to Graphics function.9.3 Example Map Pair #3

Don’t copy this (poor) layout design – use your own knowledge and judgment. Remember this map pair uses the same data for each map – it is demonstrating the effects of classification. Your goal should be to make a clean, useful legend for each map - make it look better than the legend design below.

Visual Guide Figure 5.16. Example Map Layout #3.

10. Additional Tips

Think about color and what you are mapping. Are you mapping insured or uninsured? Choose colors wisely – what do they represent?

Remember that you can employ text to explain your map! Use text sparingly but effectively – don’t be afraid to use convert to graphics and/or manually edit text and layout elements. When choosing a color scheme as well as when doing your write-up, keep in mind: the perceptual progression of your data should match the perceptual progression of your color scheme.

Credit for all screenshots is to Cary Anderson, Penn State University; Data Source, US Census Bureau.

Summary and Final Tasks

Summary and Final Tasks mxw142Summary

Congrats on making it to the end of Lesson 5! In this lesson, we learned about color, data classification, and choropleth maps - three topics that are quite inter-related. During our discussion on color models and human color vision, we talked about how to select appropriate color schemes to choropleth maps that represent quantitative data. We learned how to choose a color scheme for a map based on the perceptual progression of our data, as well as how to consider other factors such as map purpose, color accessibility, and data context. We also explored ideas related to data classification. We specifically focused our attention on how to choose a classification method and how that choice can affect the information presented on the map. Choropleth symbolization, while commonly used to map quantitative data, does present limitations in that data are aggregated to an enumeration unit and are assumed to be continuous across that unit which may not be how the data truly are distributed.

In Lab 5, we made pairs of choropleth maps. In doing so, we took on the challenge of making maps that work well both independently and when viewed together. We also compared the visual effect of classed vs. unclassed maps, and considered the impact of each method on reader perception of our maps. In building our final map layouts, we utilized knowledge from earlier lessons, such as legend and layout design. As we move forward with the course, the skills we learn will continue to build upon each other. We will design some more interesting map layouts in Lab 6!

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson 5 tasks!

You have reached the end of Lesson 5! Double-check the to-do list on the Lesson 5 Overview page to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Lesson 5.