Module 11: Human-Environment Interactions

Module 11: Human-Environment Interactions jls164Overview

Human-Environment Interactions: Resilience, Vulnerability, and Adaptive Capacity (RACV) of Food Systems

In Module 11, we focus on human-environment interactions in food systems under stress. Just as a human body does not persist in a constant state of perfect health, farms, fisheries and other components of food systems face adversity. These components must have sources of resilience and restoration to overcome these challenges. Shocks and perturbations from the natural world are a major negative coupling force from the natural systems to human societies and are sometimes compounded by problems and crises within societies. Such shocks are most evident where the natural world meets human management in production areas, and so Module 11.1 focuses on the resilience and vulnerability of agriculture. As a premier example of this, we build on the material from module 2 and learn about the way that humans’ manipulation of seeds and plant varieties has created agrobiodiversity. Agrobiodiversity, along with crop management techniques, make food production systems resilient or vulnerable to shocks and perturbations. In Module 11.2 we take up the theme of food access and food insecurity as a major example of vulnerability and an ongoing challenge for a significant proportion of humanity. Food insecurity also manifests as acute crises that carry the formal designation of famines. We will also study these since they are large-scale failures of the modern food system, which currently produces enough food for every person on earth. Just as health sciences and medicine are ways to improve and guarantee health for all persons, our hope is that by understanding vulnerability and resilience in food systems we can address food insecurity for all people as a facet of sustainable food systems. Addressing food insecurity is a serious consideration that you will contemplate in your capstone project.

Goals and Learning Objectives

Goals and Learning Objectives mjg8Goals

- Describe the concepts of resilience, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability (RACV) in a food system.

- Explain food access and food insecurity as a key challenge to food systems.

- Appraise the value of human seed systems and agrobiodiversity as human system components that incorporate crops as natural components and foster resilience.

- Apply concepts of RACV to understand changes in seed systems and food production in examples.

- Analyze stresses and shocks from climate change and food system failure that lead to both gradual changes in food systems and acute crises such as famines.

Learning Objectives

After completing this module, students will be able to:

- Define the concepts of perturbations and shocks, resilience, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability in the context of agri-food systems.

- Define and describe agrobiodiversity within food production systems and changes in this agrobiodiversity over time.

- Define the concepts of food access, food security, food insecurity, malnutrition, and famine.

- Give examples of resilience, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability in food systems.

- Give examples of support systems for biodiversity in land use and food systems.

- Evaluate recent examples in land use and food systems of resilience, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability (RACV).

- Analyze an example of a recent famine and understand how multiple factors of vulnerability and shocks combine to create widespread conditions of food insecurity known as famines.

- Understand scales at which resilience and vulnerability come into play, including farm, community, regional, and international scales.

- Propose principles embodying RACV for incorporation into a proposal/scenario for an example food system (capstone project).

Module 11.1: Resilience, Adaptive Capacity, and Vulnerability (RACV): Agrobiodiversity and Seed Systems

Module 11.1: Resilience, Adaptive Capacity, and Vulnerability (RACV): Agrobiodiversity and Seed Systems azs2In this module, we consider resilience, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability (RACV) of food systems through the lens of agrobiodiversity and seed systems. We will build on the awareness of human-natural system interactions that was explored in module 10.2. In this module, we examine the way that shocks and perturbations affect human systems and the ways in which human systems have found to cope with these shocks that produce resilience within food systems. You will learn about agrobiodiversity at a crop and varietal level as an important case of adaptive capacity that provides resilience to shocks for food systems within different types of food systems (e.g. smallholder, globalized). You will apply this learning to examining RACV in a case study from the southwestern United States.

Perturbations and Shocks in Agri-Food Systems

Perturbations and Shocks in Agri-Food Systems azs2Perturbations and shocks are common in food systems and involve both the “natural system” components and the “human system” components in these systems. Throughout modules 11.1 and 11.2, we will use the word shocks and perturbations fairly interchangeably to refer to these negative events that challenge food systems and their proper function, although the word "shock" denotes a perturbation that is more sudden and potentially disastrous. Perturbations and shocks in “natural” components include dramatic changes in climate factors such as rainfall, as well as changes brought on by biological components such as disease and pest outbreaks that affect plants and livestock. Similarly, perturbations can occur within the “human system” components of a system. For instance, food prices are rarely entirely constant and farmers and consumers are said to face "price shocks" in the purchasing of food.

Extreme conditions can result in major perturbations and shocks in agri-food systems. Major climate variation, such as severe or prolonged drought, is a common example with regard to major changes emanating from the natural system (see figure 11.1.1). Gary Paul Nabhan, the author of the required reading in this module, uses the example of the extreme "Dust Bowl" drought in the United States in the 1930s. Since it is already a region that receives little rainfall, the agri-food systems in the U.S. Southwest were considerably threatened by this drought. Extreme conditions endangering food-growing and availability can also arise in human systems. Examples include political and military instability as well as market failures and volatility (such as the sharp increase in prices).

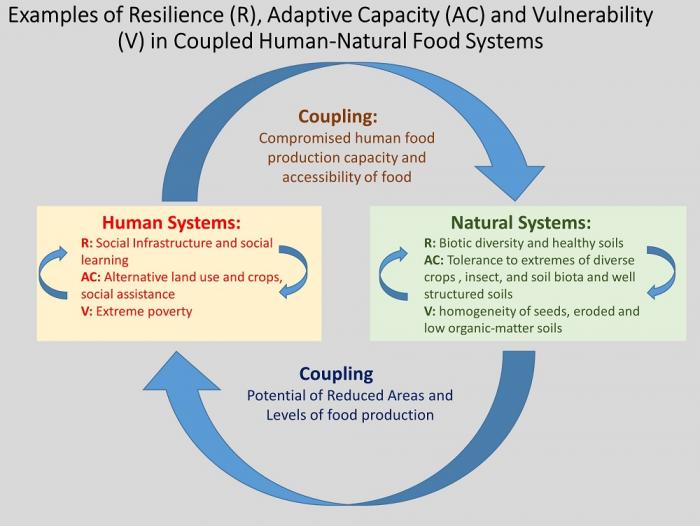

The human-environment dynamics of major perturbations and shocks in agri-food systems are shown in figure 11.1.3. This figure uses the already familiar approach of Coupled Natural-Human Systems (CNHS) introduced in Module 1 and applied in module 10 and throughout the course. Here we apply it to interactions of the natural and human systems that result in reduced production and accessibility of food. The human response to perturbations and shocks can be understood by applying the CNHS framework to agri-food systems. Within this diagram, we also want to emphasize that because of the coupling and interactions within and among these systems, the human and natural systems are never just passive recipients of a shock. Both subsystems have mechanisms for responding that can either ameliorate or worsen the "crisis" effects of perturbation. These system properties and responses to shocks are considered through the concepts of resilience, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability (RACV), defined on the next page. In the next module (11.2) we will use the RACV and human-natural systems framework to understand shocks and system responses that result in famine and severe malnutrition.

Defining Resilience, Adaptive Capacity, and Vulnerability

Defining Resilience, Adaptive Capacity, and Vulnerability azs2Introductory Video and Knowledge Check

Please watch the brief video about resilience and adaptive capacity. The presenter, Terry Chapin of the University of Alaska- Fairbanks, is an ecosystem ecologist who is used to thinking about the stresses that whole systems like ecosystems and food systems confront. Note that he uses the term 'resources' as roughly equivalent to the components of natural systems that support coupled human-natural food systems presented on the previous page. After the video in the knowledge check activity below, we'll ask you to identify the types of resources (i.e. components of natural systems) we've presented as vital to food systems in this course. You should, therefore, think about how the example he presents of Alaskan Native American communities and peoples can extend to many other elements of the food system.

Video: Resilience: The importance of adaptive capacity (2:10)

Knowledge Check Activity

Based on your learning in the course so far:

Question 1 - Short Answer

Try to quickly think of two important resources for food production like the ones described in this video. For each of the three, think of threats that confront these resources in their role of affecting food production.

ANSWER:

- Example 1

Resource: water

Threat: drought, climate change, decreased soil water holding capacity, depletion of aquifers (don't need to have all these, just examples) - Example 2

Resource: Soils and soil nutrients

Threat: soil erosion, too little manure, fertilizer, organic matter, and other soil inputs being returned to soils, urbanization, and loss of agricultural land base - Example 3

Resource: Crop production

Threat: pests, diseases, and weeds

Question 2 - Short Answer

Can you guess some examples of "adaptive capacity" by human systems within food systems we've seen so far?

Policies to regulate water use and water pollution, breeding of resistant crops, measures to maintain soil health, creation of irrigation systems, crop insurance

Definitions of Resilience, Adaptive Capacity, and Vulnerability

Resilience, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability (RACV) are three concepts used to explain how human and natural systems respond to perturbations and shocks. We can use these concepts to understand the responses of agri-food systems to such factors as drought or the occurrence of market shocks or political crises. Here are some definitions of the RACV concepts, understood within a Coupled Natural-Human System Framework.

Resilience

Resilience is a system property which denotes the degree of shock or change that can be tolerated while the system maintains its structure, basic functioning, and organization. Talking about resilience usually implies thinking about the resilience “OF what TO what”. That is, we need to understand the resilience of a system (what system or process?; e.g. crop production; food distribution; farming or culinary knowledge) TO a threat or shock (what kind?; e.g. drought, war, plant disease). A recent report from a United Kingdom scientific commission states that resilience is “the capacity to absorb, utilize or even benefit from perturbations, shocks and stresses” which includes the idea that resilient systems, provided they are sufficiently robust, can even benefit from perturbations.

Adaptive Capacity

Adaptive capacities are the social and technical skills and strategies of individuals and groups that are directed towards responding to environmental and socioeconomic changes. In the context of food systems, adaptive capacity is usually exhibited or deployed to maintain livelihoods, food production, or food access. In the context of climate change, it is important to distinguish between adaptive capacity vs. mitigation: Adaptive capacity is deployed to adapt to perturbations in growing or living conditions or shocks brought on by climate change. Mitigation involves actively reducing the threat of climate change, rather than adapting to its effects: for example reducing emissions, reducing meat consumption among high-meat consuming populations, or geoengineering of the atmosphere to reduce CO2 concentrations.

Adaptive capacity is the second important property that refers to the responsiveness of agri-food systems when faced with extreme conditions. Human systems might, for example, have the capacity to switch to alternative land use within the agri-food systems. In these cases, people would be able to adapt to change since they have the capacity to shift their use of land and other resources. Adaptive capacity in the case of natural systems is exemplified by drought-tolerant crops (figure 11.1.5). Such crops may have more developed root systems or biological adaptations for conserving moisture.

Vulnerability

Vulnerability is the exposure and difficulty of individuals, families, communities, and countries in coping with shocks, risk, and other contingencies. This can be thought of as the opposite of adaptive capacity, with a continuum of mixed adaptation/vulnerability in between the two extremes of adaptive capacity and vulnerability. Farmers and consumers in extremely poor and isolated circumstances (whether in urban or remote areas) can be considered highly vulnerable because they lack their own ability to adapt to threats, and may be cut off or marginalized from external resources (family, government assistance etc.) that allows them to adapt to changes.

Now we can apply the concepts of resilience, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability to agriculture and food, using a Coupled Natural-Human System (CNHS) framework (Figure 11.1.6)

Figure 11.1.6. Examples of Resilience (R), Adaptive Capacity (AC), and Vulnerability (V) in coupled agri-food systems. These examples are shown interior to each of the human and natural systems. Many of the positive practices regarding soils, water, and pests in the previous modules of the course can be considered additional examples of adaptive capacity because they contribute to greater levels of resilience to shocks, in addition to increasing or maintaining production under average conditions.

Examples of Resilience (R), Adaptive Capacity (AC), and Vulnerability (V) in Human systems and natural systems

Human Systems:

R: Social infrastructure and social learning

AC: Alternative land use and crops, social assistance

V: Extreme poverty

Natural Systems:

R: Biotic diversity and healthy soils

AC: Tolerance to extremes of diverse crops, insect, and soil biota and well structured soils

V: homogeneity of seeds, eroded and low organic-matter soils

As shown in Figure 11.1.6, resilience can be found in both the natural and human subsystems of food systems. You may recognize that many of the examples of natural system adaptive capacity refer to the "best practices" that we have advocated for water, soils, crops, and pest management in sections II and III of this course. These would include examples such as reducing the water footprint of food production, managing soils in a system framework for greater "soil health", and managing pests with ecological practices that seek to avoid pest and weed resistance to our management approaches (Modules 4, 5, 7, and 8 respectively). These approaches are not only important in increasing productivity under average conditions, but also help a food production system to adapt to shocks and perturbations.

Meanwhile, the human component of coupled human-natural food systems also is a vital part of resilience and adaptive capacity. Resilience is higher where there are higher levels of social infrastructure that enable people to share learning and resources in response to shocks and perturbations, such as extreme drought. Social infrastructure, shown in Fig. 11.1.6, includes mutual assistance within families and communities or among regions in a country, coordinated by governments to assist in the case of shocks that affect food production. Social learning is vitally important since it’s one of the main ways that people would learning new techniques based on the conditions prevailing in their area. For example, farmers could use social learning to acquire the skills and knowledge to lessen water use, and thereby lessen the degree of agricultural production decline and reduced food access. Biological diversity is a major example of higher resilience functioning in the natural components of coupled agri-food systems. Food production systems with more biological diversity---a property referred to as agrobiodiversity and covered on the next pages---typically have the capacity for greater levels of resilience. This greater level of resilience may result from a mixture of crops and varieties combining vulnerable and resistant type of crop, for any given stress, so that even if some crops fail, others will do well. Different crops and land uses may also produce positive or facilitating interactions in which one crop type or wild plant species, for example, provides benefits to another (e.g. nitrogen fixation and better soils or screening from an important pest; see module 6 on crops and the previous section on systems approaches for management for additional examples).

Resilience vs. Adaptive Capacity: What's the Difference?

On the surface, resilience and adaptive capacity in systems may seem very similar, and it is true that as defined here they are very aligned. One way to remember the difference is that resilience is a broader system property that may have to do with the interplay of human and natural systems, or one or the other of these subsystems. We can say that a region's food system is quite resilient to drought (a more general statement) if we think for a number of reasons that its food supply would be able to continue mostly without issues during a drought. Adaptive capacity meanwhile is more narrowly focused on the specific skills and mechanisms that are deployed by human systems to contribute to resilience. In other words, we might identify that the system or component thereof is resilient (like the region mentioned above), and then identify sources or mechanisms of resilience in terms of particular knowledge, practices, land uses, or biological properties that are functioning in a food production system, referring to these as adaptive capacity. We turn next to agrobiodiversity as an example of adaptive capacity that can contribute to food system resilience (can you see the difference between the two words in this last sentence?).

Agrobiodiversity: Biological Diversity and Associated Human Capacity in Agri-food Systems

Agrobiodiversity: Biological Diversity and Associated Human Capacity in Agri-food Systems azs2One major way of increasing the resilience and adaptive capacity of agri-food systems in response to perturbations and shocks is to be certain they contain components with high levels of agrobiodiversity.

Here is a standard definition of agrobiodiversity:

Agricultural biodiversity…includes the cornucopia of crop seeds and livestock breeds that have been largely domesticated by indigenous stewards to meet their nutritional and cultural needs, as well as the many wild species that interact with them in food-producing habitats. Such domesticated resources cannot be divorced from their caretakers. These caretakers have also cultivated traditional knowledge about how to grow and process foods.. (which) is the legacy of countless generations of farming, herding and gardening cultures.

This definition is taken from Gary Nabhan’s book Where Our Food Comes From and is based on work of the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO)

There are two important points to note about this definition:

- First, and most importantly, the biological diversity of agri-food systems includes vital coupling to the human system, most directly the people who are growers and their skills, knowledge, and other factors. These growers are “caretakers” in Nabhan’s definition; see Fig. 11.1.7 for potato varieties and a representative "caretaker" - a local farmer with working knowledge of these varieties. Agrobiodiversity exists squarely at the intersection of human and natural systems conceptualized in this course.

- Second, it encompasses both our cultivated species of plants and animals, which are crops and livestock chosen and evolved for production, as well as their still living wild relatives and the biodiversity of the ecosystems associated with this production (both the agroecosystem itself and the surrounding uncultivated ecosystem). Agrobiodiversity production in the natural system must be sufficient to offer positive feedbacks into the human system in order to offer the incentive for continued production.

The above-mentioned points in the definition of agrobiodiversity are illustrated in figure 9.6, which depicts agrobiodiversity as a Coupled Human-Natural System (CNHS).

The growers of agrobiodiversity range widely around the world. They include the people of traditional and indigenous cultures who often live in more remote locations. Many of these people live in mountainous regions and hill lands of the tropics and sub-tropics. Their use of agrobiodiversity in agri-food systems is reflected in certain global centers of diversity, as shown in the map that we presented in Module 2 regarding the sites of crop domestication in the early history of food systems. Such centers are sometimes called “Vavilov Centers” in recognition of the pioneering contribution of the scientist Nikolay Vavilov in the 1920s.

Increasingly it’s recognized that significant agrobiodiversity also occurs outside the Vavilov Centers. For example, many urban and peri-urban dwellers grow small fields and gardens as part of local, small-scale agri-food systems. Producers of diversified production for local markets in North America and Europe are still another important group of agrobiodiversity-growers.

The extent of agrobiodiversity, in terms of crops and livestock, may vary from only a few types in a field or farm to many dozens. Agri-food systems with only a few types are quite important since they can confer significant resilience to perturbations and stressors. For example, cultivation of only a few types of barley, wheat, or maize (“corn” in the U.S.) among neighboring farms and communities can offer a much higher degree of resilience than the monoculture of a single type.

Equally important is the case of the megadiverse agri-food systems. In the potato fields of the Andes Mountains of western South America, for example, a farmer may grow as many as 20-30 major types of potatoes in a single field. (Figure 11.1.11). Here, in tha global “Vavilov Center” of the Andes mountains, high levels of agrobiodiversity are integral to the agri-food system as a result of factors in the human system (skills, knowledge, labor-time, cultural and culinary preferences) and the natural system (highly varied climate and soil conditions characteristic of tropical mountains).

Activate Your Learning: Agrobiodiversity and Resilience

Assigned Reading:

Please read the brief "introduction to the reading" below and then the following pages from Gary Nabhan's book "Where Our Food Comes From":

Nabhan, G.P. "Rediscovering America and Surviving the Dust Bowl: The U. S. Southwest ", p. 129-138, part of Chapter 9, Where Our Food Comes From: Retracing Nikolay Vavilov's Quest to End Famine. Washington: Island Press.

Introduction to the reading: The reading describes part of a much longer account of travels by Vavilov (for whom the Vavilov centers of agrobiodiversity are named, see the previous page in the book, and module 2.1 in this course) from 1929 to 1934 in North America. During this trip, the Russian crop researcher met with U.S. researchers as well as "keepers" of U.S. native agrobiodiversity. This chapter describes Vavilov's trip to the Hopi Indians in 1930, in which he and the U.S. scientists were able to observe firsthand the seed systems and their resilience to the drought that was currently going on in the United States. The author of the book, Gary Nabhan, relates this account of the visit and then compares it to similar visits he made to the Hopi in the more recent past. This compiled history of seed systems and their relation to both human and natural system changes in the U.S. Southwest is a sort of case study, from which the assessment worksheet will ask you to draw conclusions.

Download Worksheet

Activate Your Learning

This exercise requires you to fill in some of the blanks in the worksheet based on the reading.

Two of the shocks that the Hopi food system has been exposed to have already been filled in on the worksheet, the main one being periodic drought. Within the human system box, fill in some of the agricultural methods (ways of growing food) described by Nabhan that represent adaptive capacity to drought shocks.

Click for answer.Deep planting of crops to capture moisture, spring-fed terraces, stream-side fields to capture flood moisture.In the natural system box, fill in how agrobiodiversity and their seed systems also represented adaptive capacity of the Hopi against drought.

Click for answer.Diverse crops adapted to local conditions, local seed saving so that seeds were not lost, tree crops and edible wild plant gathering to supplement diet.During the more recent drought, Nabhan states that an additional climatic factor related to climate change tended to worsen the effects of drought. What was this? Place it in the additional shock box at the lower edge of the diagram.

Click for answer.Hotter summer temperatures due to climate change.A shock that emerged from the human system was the pumping of groundwater for coal mining and coal slurry transport in the region. What was the vulnerability to drought in the local natural system that this water extraction created? Fill it in in the “vulnerabilities” box in the natural system part of the diagram.

Click for answer.Pumping of groundwater for coal mining dries out springs and reduces the availability of spring water for irrigated terraces.In the last part of the chapter, Nabhan notes first a social/cultural vulnerability that has emerged in recent times. What is this social vulnerability? Note it in the vulnerability space of the Human System rectangle.

Click for answer.Shift toward salaried work in cities by young people within the community.Nabhan also notes a new social adaptive capacity that has arisen to challenge this vulnerability. What is this newest change that gives Nabhan hope about the fate of Hopi seed and agricultural systems?

Click for answer.Hopi organizations that seek to revitalize farming traditions and the Hopi food system.Of the three shocks now documented in the diagram, to which one would the Hopi knowledge system and adaptive capacity been most exposed to over recent centuries? Answer in one sentence.

Click for answer.Likely, drought would have been a recurrent shock with which Hopi knowledge systems and adaptive capacity would have been familiar.Compare the level of success the Hopi food system had in adapting to the older, better-known shock you chose in (7), in comparison to the other two shocks, at least during the last thirty years. (3-4 sentences, this may make the page run over to the next).

Click for answer.It was more challenging to adapt to these later shocks – their effects may have been unfamiliar based on long experience, and also they tend to affect not just production but the very means of existing adaptive capacity, for example limiting the effectiveness of known farming strategies (e.g. spring-fed terraces) or the entire knowledge system from which the Hopi drew their adaptive capacity. (some version of the above is acceptable as an answer: explain that it is more challenging and some reference to why that was so)

Module 11.2: Food Access and Food Insecurity

Module 11.2: Food Access and Food Insecurity azs2In this module, we will introduce the concepts surrounding the global challenge of food access and insecurity and the vulnerability of agri-food systems and particular populations to market and climate shocks. The concepts used in this unit build on the ideas of shocks and perturbations, resilience, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability of agri-food systems that were covered in unit 11.1. The unit, therefore, illustrates an urgent aspect of the analysis of the agri-food system as a coupled natural-human system.

Introduction to Food Access, Food Security, and Food-Insecure Conditions

Introduction to Food Access, Food Security, and Food-Insecure Conditions azs2Food access is a variable condition of human consumers, and it affects all of us each and every day. If you have ever traveled through an isolated area of the country or the world and encountered difficulty in encountering food that is customary or nutritious to eat, or within reach of your travel budget, you have an inkling of what it means to have issues with food access. For those with little capacity for food self-provisioning from farms or gardens, food access is determined by factors influencing the spatial accessibility, affordability, and quality of food sellers. The consistent dependability of adequate food access helps to enable food security whereby a person’s dietary needs and food preferences are met at levels needed to main a healthy and active life. Famines are conditions of extreme food shortage defined by specific characteristics (see below). Food-insecure conditions, such as acute and chronic hunger, are important conditions that affect many people both in the United States and in other countries.

Global Overview of Food Insecurity: Food Deficit Map and Required Readings

Global Overview of Food Insecurity: Food Deficit Map and Required Readings azs2A global overview of food insecurity can be obtained by mapping the average daily calorie supply per person for each country (see Figure 11.2.1). Mapped values are shown as ranging from less than 2,000 calories per person (e.g., in Ethiopia and Tanzania) to the range of 2,000-2,500 calories per person, which covers several countries in Africa as well as India and other countries in Asia in addition to Latin America and the Caribbean. Calories are a reasonable way to begin to understand large-scale patterns related to the lack of food access around the world. Nevertheless just looking at calories hides other aspects of human nutrition, such as the need for a diverse diet that satisfies human requirements for vitamins, minerals, and dietary fiber, which were described in module 3.

Required Readings

The following brief readings are good ways to appreciate the analyses and debates surrounding food insecurity and the challenges of "feeding the world", especially in the emerging scenario of climate change impacts on food production. They form part of the required reading for this module and will help you to better understand the materials and the summative assessment.

- Bittman, Mark. "Don't Ask How to Feed the 9 Billion" NYT, Nov 12, 2014. (Note: The link is available only for users with Penn State accounts.)

- Deering, K. 2014. Stepping up to the challenge – Six issues facing global climate change and food security, CCAFS (Climate Change and Food Security Program)-UN (United Nations), 2014. Read the page headings on each challenge and the brief description of the response below.

Food Shortages, Chronic Malnutrition, and Famine: Coupled Human-Natural Systems Aspects

Food Shortages, Chronic Malnutrition, and Famine: Coupled Human-Natural Systems Aspects azs2Food Crises and Interacting Elements of the Natural and Human Systems

This section employs the framework of Coupled Natural-Human Systems (CHNS) in order to illustrate the interacting elements of natural and human systems that can combine to produce severe food shortages, chronic malnutrition, and famine food systems around the world. These CHNS concepts build on the diagrams and concepts in modules 10 and 11.1. You will also apply these concepts in the summative assessment on the next page.

As you read this brief description consult figure 11.2.2 below. It depicts that interacting conditions within the human and natural systems, combined with driving forces and feedbacks, are at the core of many cases of severe food shortages, chronic malnutrition, and famine in agri-food systems.

The best place to begin interpreting Figure 11.2.2 is by focusing on the driving forces emanating out of both the human and natural systems. Human system drivers often involve political and military instability and/or market failures and volatility (such as prices). Most cases of famine, as well as many instances of severe food shortages and chronic malnutrition, involve these human drivers. In addition, human drivers not only drive vulnerability in natural systems but may act first and foremost on human systems, reducing the adaptive capacity of consumers and producers, for example by reducing the purchasing power of poor populations during price spikes.

Figure 11.2.2 also shows that drivers emanate from the natural system. Climate change and variation, such as drought and flooding, often contribute to cases of famine, as well as severe food shortages and chronic malnutrition.

These drivers, however, are only PART of the causal linkages of severe food shortages, chronic malnutrition, and famine. Similarly important are the conditions of poor resilience (potentially arising as result of weak social infrastructure), low levels of adaptive capacity and poverty. Poverty is tragically involved as a cause of nearly all cases of severe food shortages, chronic malnutrition, and famine. For Mark Bittman, the author of the required reading on the previous page, the link between poverty and failures of food systems, rather than a failure of any other human or natural factors such as food production, food distribution, or overpopulation, is the central thesis he advances in his short opinion piece. You may want to glance again at this reading in order to remind yourself of why poverty is so deeply implicated in the failures of agri-food systems.

Weak or inadequate resilience (R) and adaptive capacity (AC), along with vulnerability (V), are also symptomatic of natural systems prone to severe food shortages, chronic malnutrition, and famine. For example, cropping and livestock systems unable to tolerate extreme conditions illustrate a low level of adaptive capacity (AC) that can contribute significantly to the failure of agri-food systems.

Summative Assessment: Anatomy of a Somali Famine (2010 - 2012)

Summative Assessment: Anatomy of a Somali Famine (2010 - 2012) azs2Instructions

Download the worksheet and follow the detailed instructions provided.

Files to Download

See worksheet on next page.

Anatomy of a Famine: multifactorial failures of adaptive capacity to climate and social shocks.

This worksheet relies heavily on the data resources presented by the Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit – Somalia and the Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS Net).

This worksheet uses maps, tables, and graphs to guide you in analyzing a tragic famine in Somalia between 2010 and 2012 as a case of adaptive capacity and vulnerability (see Module 9.2 for the definition of a famine). As many as 260,000 people died in this famine, half of them children under five years old (optional: see Somalia famine 'killed 260,000 people', May 2, 2013). You should read carefully through the case study presented in the worksheet (download above) and answer the question in each section, e.g. “Question A1” and the two summary questions at the end.

Submitting Your Assignment

You do not need to submit your worksheet; it will instead act as a guide for you to complete the summative assessment quiz.