Welcome to Alternative Fuels from Biomass Sources!

Welcome to Alternative Fuels from Biomass Sources! ksc17Course Overview

This course will examine the chemistry of technologies of bio-based sources for power generation and transportation fuels.

When you successfully complete this course, you will be prepared to:

- describe various biomasses that can be utilized for energy and fuel generation;

- explain the composition of various processes necessary for biomass processing;

- utilize the necessary chemistry, as well as mass and energy balances, that would be utilized in a biorefining facility;

- analyze how to utilize biofuels in current fuel infrastructure;

- illustrate what is required in a biorefinery.

Instructor Information

Dr. Hilal Ezgi Toraman leads an interdisciplinary research program at Penn State focused on sustainable reaction engineering and catalysis for the valorization of non-traditional carbon feedstocks. Her group integrates advanced pyrolysis experimentation, GC×GC-based analytics, and kinetic modeling to develop and optimize scalable chemical recycling technologies. She leads multi-institutional projects on mixed polymer pyrolysis and catalytic upgrading, where her group contributes intrinsic kinetic studies, GC×GC method development, and data management and analysis infrastructure to support process design and evaluation.

Toraman has secured over $5 million in research funding as a PI, published widely in high-impact journals, and received both national and international recognition, including the C&EN Talented 12, AIChE CRE Pioneers in Catalysis and Reaction Engineering, and ACS Energy & Fuels Rising Star awards. She has held leadership roles as Director of AIChE's Catalysis and Reaction Engineering Division and currently serves as president of the Pittsburgh-Cleveland Catalysis Society. Her honors include the Virginia S. and Philip L. Walker Jr. Faculty Fellowship and the Wilson Fellowship.

Before joining the Penn State faculty, Toraman was a postdoctoral researcher with the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering and Delaware Energy Institute at the University of Delaware. She received her B.S. and M.S. degrees in Chemical Engineering from Middle East Technical University, Türkiye (Turkey), and her Ph.D. degree in Chemical Engineering from Ghent University, Belgium.

Teaching Assistant

Praneetha Buddha

PhD Candidate

Department of Energy and Mineral Engineering

Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA

Email: pjb5926@psu.edu

- Email: Please use the Canvas course email system to reach the assistant and me.

- Phone: 814-863-9261 (Office). The phone should be your last option. The best way to reach me is by email.

- Office Hours: Office hours are by appointment on Wednesdays, between 1:00 PM and 2:00 PM (Ms. Buddha and Dr. Toraman), on Mondays, between 11:00 AM and 12:00 PM, and on Thursdays, between 2:00 PM and 3:00 PM (Ms. Buddha). Please contact us before Sunday at 11:59 pm to schedule for the following Wednesday. I can be reached at hzt5148@psu.edu, and the Teaching Assistant, Praneetha Buddha, can be reached at pjb5926@psu.edu. When contacting us to schedule, please provide the question(s) that you plan to ask during the office hours.

- Syllabus: All students sign and return the Syllabus Acknowledgement Form to the Teaching Assistant via email, during the first week of the semester.

This course is offered as part of the Repository of Open and Affordable Materials at Penn State. You are welcome to use and reuse materials that appear on this site (other than those copyrighted by others) subject to the licensing agreement linked to the bottom of this and every page.

Want to join us? Students who register for this Penn State course gain access to assignments and instructor feedback and earn academic credit. Official course descriptions and curricular details can be reviewed in the University Bulletin.

Lesson 1: Why Alternative Fuels from Biomass?

Lesson 1: Why Alternative Fuels from Biomass? mjg8Overview

Not everyone likes the idea of using biomass for energy. From an industrial perspective, it competes with the coal and petroleum industries. There is a great deal of skepticism regarding the production of ethanol or bio-oil and how much energy is used to make them. Many people don't understand its value or how it can be incorporated into the current energy portfolio. This lesson will explain why using biomass as an energy source is smart and can alleviate the increasing energy demand. You will also read some excerpts from books that take a particular slant on bioenergy use. And you'll also see that some sources have a hidden agenda that may not be the best strategy for incorporating biofuels.

Lesson Objectives

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- explain why biofuels are a necessary part of our energy portfolio.

Lesson 1 Road Map

This lesson will take us one week to complete. Please refer to the Course Syllabus for specific time frames and assignment due dates.

Questions?

If there is anything in the lesson materials that you would like to comment on or don't quite understand, please post your thoughts and/or questions to our Throughout the Course Questions and Comments discussion forum. The discussion forum will be checked regularly. While you are there, feel free to post responses to your classmates if you can help. Regular office hours will be held to provide help for EGEE 439 students.

1.1 Why Biofuels?

1.1 Why Biofuels? ksc17Part of the purpose of the course is to help you to understand why biofuels are needed and how to make them, at the current state-of-the-art.

Why biofuels? To look at the situation a little more broadly, the question then becomes: why alternative fuels?

As climate change becomes an issue of ever-stronger concern in the world, stronger efforts are being devoted to tackling this issue. The International Energy Agency (IEA) has recently proposed the 2°C scenario (2DS) as a way to handle the climate change issue. The 2DS has become a largely used quote by many policymakers and scientists. The 2DS scenario requires that carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in 2060 should be reduced by 70% in comparison to the 2014 level. The transport sector plays an important role to achieve this goal, considering that the transportation sector is responsible for about 23% of total CO2 emissions. Although electricity has been considered a promising option for reducing CO2 emissions in transportation (Yabe, Shinoda, Seki, Tanaka, & Akisawa, 2012), transport biofuel is estimated to be the key alternative energy in the transport sector (Ahlgren, Börjesson Hagberg, & Grahn, 2017). The share of biofuels in total transportation-fuel consumption by 2060 is predicted to be 31%, followed by electricity at 27% based on the mobility model results of IEA for the 2DS. Biofuel production must be increased by a factor of 10 to achieve this goal (Oh, Hwang, Kim, Kim, & Lee, 2018). In addition to the need for climate change adaptation, the increasing concerns over energy security is another main driver for the policy-makers belonging to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to promote the production of renewable energy (Ho, Ngo, & Guo, 2014). Last but not least, world energy demand will continue increasing. The world energy demand was 5.5 x 1020 J in 2010. The studies predict an increase of a factor of 1.6 to reach a value of 8.6 x 1020J in 2040. The bioenergy delivery potential of the world's total land area excluding cropland, infrastructure, wilderness, and denser forests is estimated at 190 x 1018 J yr-1, 35% of the current global energy demand (Guo, Song, & Buhain, 2015).

In short, there are three main reasons to develop biofuels:

- to meet the needs of increasing energy demand;

- to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions; and

- to improve energy security by reducing dependence on foreign fuel sources because it can be problematic, depending on US domestic fuel production.

We will explore each of these reasons in more depth in the following sections.

References

Ahlgren, E. O., Börjesson Hagberg, M., & Grahn, M. (2017). Transport biofuels in global energy–economy modeling–a review of comprehensive energy systems assessment approaches. Gcb Bioenergy, 9(7), 1168-1180.

Guo, M. X., Song, W. P., & Buhain, J. (2015). Bioenergy and biofuels: History, status, and perspective. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews, 42, 712-725. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2014.10.013

Ho, D. P., Ngo, H. H., & Guo, W. (2014). A mini review on renewable sources for biofuel. Bioresource Technology, 169, 742-749. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2014.07.022

Oh, Y. K., Hwang, K. R., Kim, C., Kim, J. R., & Lee, J. S. (2018). Recent developments and key barriers to advanced biofuels: A short review. Bioresource Technology, 257, 320-333. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2018.02.089

Yabe, K., Shinoda, Y., Seki, T., Tanaka, H., & Akisawa, A. (2012). Market penetration speed and effects on CO2 reduction of electric vehicles and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles in Japan. Energy Policy, 45, 529-540.

1.2 Increasing Energy Demand

1.2 Increasing Energy Demand ksc17The energy needs of most advanced economies in the Western world are increasing at a modest level. However, in some developing economies, where the economy is booming, energy demands are increasing dramatically, e.g., in India and several African countries. The figure below shows the latest gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of the countries of the world in 2025. While advanced economies had a 1.7% annual percent change in real GDP growth, emerging and developing Asia had a 4.5% annual percent change in real GDP growth, with India having a 6.2% annual percent change in real GDP growth. Emerging and developing economies accounted for over 80% of global energy demand growth. According to the IEA's Global Energy Review 2025, global electricity consumption increased by approximately 1,100 terawatt-hours (TWh) in 2024, more than double the annual average increase over the past decade. Currently, global energy consumption is growing at around 1-2% per year. This rate is faster than the average rate over the past decade. If many third-world countries were to dramatically increase their standard of living, there are estimates that worldwide energy consumption would double. But where would that energy come from, particularly since there aren't huge stockpiles of crude oil sitting around? Petroleum cannot supply it all, and neither can natural gas or coal.

1.3 Problematic Dependence on Foreign Fuel Sources

1.3 Problematic Dependence on Foreign Fuel Sources ksc17The US is highly dependent on crude oil to produce fuels for transportation. The figure below shows how the transportation sector is almost all oil-based, and the other sources barely make a dent in the hold petroleum has. Up until the last few years, the US has been highly dependent on foreign sources of oil. In 2023, petroleum accounted for approximately 89% of the primary energy consumption in the transportation sector, but it contributed less than 1% to the primary energy consumption in the electric power sector. The chart below illustrates the various types and quantities of primary energy sources used in the United States, the primary energy consumption by the electric power sector and end-use sectors, and the sales of electricity from the electric power sector to these end-use sectors. Growth across different parts of the global energy system varied widely in 2024, shaped by both short-term influences and longer-term structural shifts. Worldwide energy demand rose by 2.2%—well above the 1.3% annual average recorded from 2013 to 2023. Around 0.3 percentage points of this increase can be attributed to the effects of extreme weather. Even so, energy use expanded at a slower pace than the global economy, which grew by 3.2% in 2024, roughly in line with its long-term trend. Electricity demand grew faster than both overall energy use and GDP in 2024, rising by 4.3%. In absolute terms, this was the largest increase ever observed outside of post-recession rebounds. The surge was driven by structural factors, including wider use of electricity-intensive appliances such as air conditioning, shifts toward electricity-heavy manufacturing, growing needs from digitalisation, data centres, and AI, and the continued electrification of end uses. Altogether, the power sector accounted for around 60% of the global increase in energy demand.

On the supply side, renewables contributed the largest share of growth (38%), followed by natural gas (28%), coal (15%), oil (11%), and nuclear (8%). However, energy intensity improved by only 1%, extending the recent trend of slower efficiency gains. Energy-related CO₂ emissions rose by 0.8%—a deceleration compared with the 1.2% increase in 2023. (IEA, 2025).”

The US was the world's largest petroleum consumer (EIA, 2012), but was third in crude oil production. Over half of the material that was imported into the US comes from the Western hemisphere (North, South, and Central America, and the Caribbean), but we also imported 29% from Persian Gulf countries (Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates).

The top 5 sources of net crude oil and petroleum imports included 1) Canada, 28%, 2) Saudi Arabia, 13%, 3) Mexico, 10%, 4) Venezuela, 9%, and 5) Russia, 5%. According to CNN Money, the US was behind Russia and Saudi Arabia in oil production for the first three months of 2016. See the World's Top Oil Producers for additional information. However, this situation recently changed, and the US became the world's largest oil producer in 2018 for the first time since 1973 and held the lead position through 2022. U.S. oil refineries obtain crude oil produced in the United States and other countries. Based on EIA, crude oil is extracted in 32 U.S. states as well as in coastal waters. In 2022, five states together made up roughly 72% of the total crude oil production in the United States. In 2022, 98 countries collectively produced around 80.75 million barrels of crude oil, with five of these nations contributing approximately 52% of the global total. The top five crude oil-producing countries and their respective shares of world crude oil production in 2022 were: The United States 14.7%, Saudi Arabia 13.2%, Russia 12.7%, Canada 5.6%, and Iraq, 5.5%. See the following link for further information see America is now the world's largest oil producer.

The image is a detailed chart titled "U.S. Energy Consumption by Source and Sector, 2023", showing how energy from various sources is distributed across different sectors of the U.S. economy. The total energy supplied by sources is 93.6 quadrillion British thermal units (Btu), while the total energy consumed by end-use sectors is 74.7 quadrillion Btu. The difference accounts for energy losses, primarily in electricity generation and transmission.

The energy sources are broken down as follows: Natural Gas accounts for 36% (33.6 quadrillion Btu), Petroleum for 35.4% (33.1 quadrillion Btu), Renewable Energy for 8.2% (7.7 quadrillion Btu), Coal for 8.1% (7.6 quadrillion Btu), and Nuclear Electric Power for 8.1% (7.6 quadrillion Btu).

The end-use sectors are Transportation at 28%, Industrial at 26%, Residential at 11.3%, and Commercial at 9.3%. These percentages represent the share of total energy consumption by each sector.

The Electric Power Sector uses 32.1 quadrillion Btu of energy. Of this, 13.2 quadrillion Btu (41%) is delivered as electricity sales to ultimate consumers, while 18.9 quadrillion Btu (59%) is lost in the electrical system due to generation and transmission inefficiencies.

The chart visually connects each energy source to the sectors it supplies, illustrating the flow of energy through the U.S. economy. For example, petroleum is primarily used in transportation, while natural gas, coal, renewables, and nuclear are major inputs for electricity generation. The chart is based on data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s Monthly Energy Review and includes notes on data rounding and definitions of primary energy consumption.

So, while oil is fairly available currently, there is extensive potentially explosive turmoil in many petroleum-producing regions of the world, and, in several places, the US's relationship with some oil-producing countries is strained. China and India are now aggressive and voracious players in world petroleum markets because of high economic growth (as pointed out in the previous section). Saudi Arabia's production is likely "maxed out," and domestic oil production peaked in 1970. While the US dependence on imported oil has declined after peaking in 2005, it is clear that if any one of the large producers decides to withhold oil, it could cause a shortage of fuel in the US and would cause the prices to skyrocket from an already high price (depending on the type of crude oil, the price of oil is currently $100-$106/bbl) (see U.S. Energy Information Administration). The figure below is a graphic showing the price level of oil from 1950 to the present. As you can see, there has been significant volatility in the price of oil in the last ~50 years. One of the first spikes came in 1974 when the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) became more organized and withheld selling oil to the US. It was a true crisis at that point, with gasoline shortages causing long lines and fights at gas stations, with people filling up only on certain days depending on their license plates. It had a high spike in 1980, but a significant low in 1986. When the price of oil hit a significant low in 1998, the government took steps to lower the tax burden on oil companies. But when the prices went back up, the law remained in place, and currently, oil companies do not have to pay taxes on produced oil. When the reduced tax burden went into place in the late 90s, it made sense, but oil companies have continued to convince Congress with lobbyists that it should stay that way. What do you think?

As seen in the figure below, there were major fluctuations in gasoline prices in the last few years. As we will discuss in a later lesson, several aspects contribute to the price of gasoline, including but not limited to the recent COVID-19 Pandemic. This is a graphic that shows the price volatility for gasoline from 1990 - 2024 (the most recent data available), and the other figure below shows a breakdown of what goes into the price of gasoline.

The image presents a side-by-side comparison of the cost breakdown for a gallon of Regular Gasoline and Diesel in June 2024, based on data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration's Gasoline and Diesel Fuel Update.

For Regular Gasoline, the average retail price is $3.46 per gallon. The cost components are distributed as follows: 55% of the price comes from the cost of crude oil, 12% from refining, 18% from distribution and marketing, and 15% from taxes.

For Diesel, the average retail price is $3.72 per gallon. The breakdown is slightly different: 51% of the cost is attributed to crude oil, 13% to refining, 20% to distribution and marketing, and 16% to taxes.

The chart visually compares these percentages using proportional segments, highlighting the differences in how each fuel type's price is structured. Diesel has a slightly higher retail price and a greater share of costs allocated to distribution, marketing, and taxes, while gasoline has a higher proportion of its cost coming from crude oil.

In recent years, petroleum became less available and more expensive, and replacement-alternative fuels emerged because the economics were beginning to become more favorable. However, due to lower demand and high petroleum supply, prices drastically dropped, which may affect the development of alternative fuels. There is one factor that will most likely reverse this trend, and that is that energy demands will continue to increase worldwide. For future transportation fuel needs, most likely a liquid fuel will be necessary, and no one source will be able to replace petroleum. In the International Energy Outlook 2021 (IEO2021) Reference case, it is anticipated that, without major policy or technological advancements, global energy consumption will rise by nearly 50% over the next 30 years. While petroleum and other liquid fuels are expected to remain the world's primary energy source by 2050, renewable energy sources like solar and wind are projected to expand to almost the same level. It is important to note that Petroleum and other liquids include biofuels.

Note: Petroleum and other liquids include biofuels.

1.4 Reduction of Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emission

1.4 Reduction of Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emission ksc17There is a scientific consensus that greenhouse gas (GHG) production is increasing, which has led to climate change and several other environmental concerns. Despite efforts to make us believe otherwise, much of the severe weather occurring worldwide is indeed due to climate change. There is a significant amount of evidence to substantiate the existence of climate change and the overall warming of the earth. Climate change is due to the Greenhouse Effect; it is a natural effect, caused by CO2 and water vapor naturally present in the atmosphere. The focus of debate (scientific and political) has been on whether there is also an anthropogenic greenhouse effect, causing further climate change. Carbon dioxide (CO2) is not the only greenhouse gas (methane, CH4 is another potent GHG; this will be discussed further in upcoming sections), but most of the debate focuses on it. It is thought that the dramatic increase in CO2 in the atmosphere is due to the burning of fossil fuels.

The world is highly dependent on fossil fuels; the US is also highly dependent on fossil fuels. As we saw in the charts in Lesson 1.3, global energy consumption will continue to increase over the next 30 years. Fossil-based sources such as coal, natural gas, and petroleum are expected to be the dominant energy source in 2050.

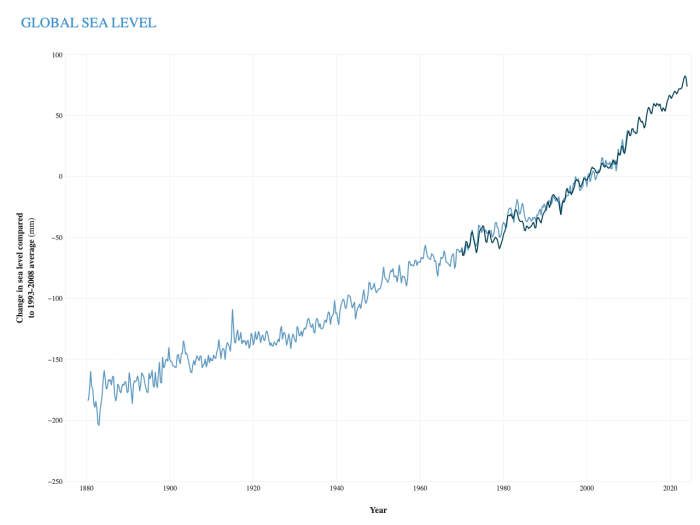

There is a mountain of evidence indicating that the planet is warming. The figure below shows global average surface temperature levels plotted from 1880-2020. The change has been most dramatic in the last 30 years. Yearly global temperatures from 1880 to 2023 relative to the 20th-century average show that Earth's surface temperature has increased by 0.14 degrees Fahrenheit per decade since 1880. The pace of warming has more than doubled since 1981.

The 2023 Global Climate Report from NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information reveals that every month in 2023 was among the seven warmest on record for that particular month. Additionally, each month from June to December marked the hottest ever recorded for those months. In July, August, and September, global temperatures exceeded the long-term average by more than 1.0°C (1.8°F)—the first time any month in NOAA's records has surpassed this threshold.

The impacts of climate change on our planet can be observed from pole to pole. NOAA tracks global climate data, and here are some notable changes they've recorded, with more details available on the Global Climate Dashboard.

- Global temperatures have increased by about 1.8°F (1°C) from 1901 to 2020.

- Sea level rise has accelerated from 1.7 mm/year during most of the 20th century to 3.2 mm/year since 1993.

- Glaciers are retreating: the average thickness of 30 well-studied glaciers has reduced by over 60 feet since 1980.

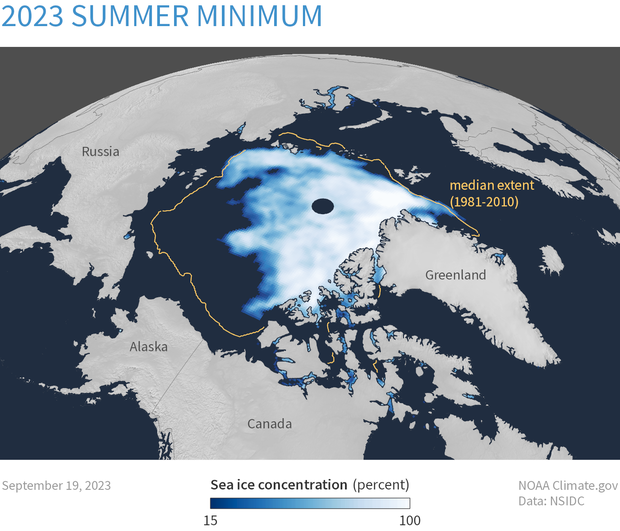

- The summer sea ice coverage in the Arctic has diminished by approximately 40% since 1979.

- Atmospheric carbon dioxide levels have risen by 25% since 1958 and by about 40% since the Industrial Revolution.

- Snow is melting earlier than long-term averages indicate.

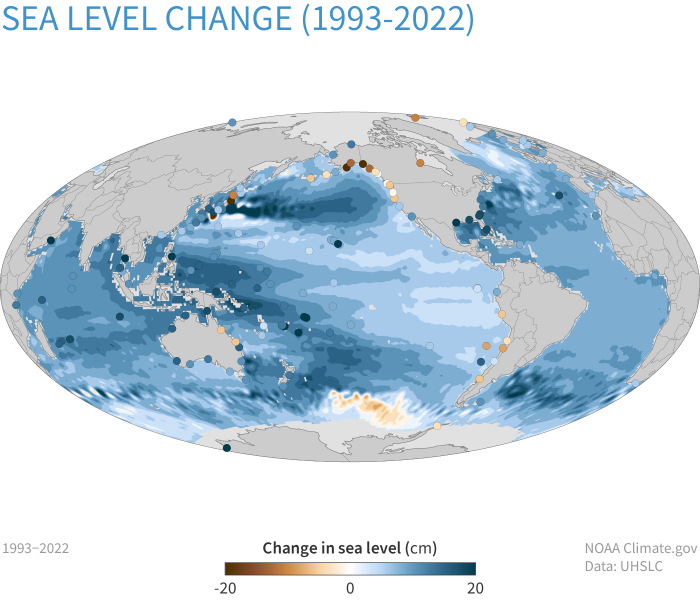

In the Arctic and Antarctic regions, the ice pack and glaciers are melting, and at an even faster rate than originally anticipated. Scientists have found that increasing atmospheric temperatures are not the only cause of this; the melting is causing water currents to shift and move warmer water around the poles, so melting is happening underneath the ice pack. The figure below shows that the total area of the Arctic Ocean with at least 15% ice coverage each September from 1979 to 2023 shows that, since 1980, the extent of ice surviving the summer has decreased by 13.1% per decade. The figure related to Sea Ice Concentration demonstrates that the sea ice concentration on September 19, 2023, compared to the 1981-2010 average extent for that date (indicated by the gold line), marked the sixth smallest summer minimum ever recorded. The sea levels have also risen by 8-9 inches since 1880, with the rate of increase accelerating during the satellite era.

Another problem could stem from the increased production of natural gas. Natural gas consists primarily of methane. Sources include petroleum and natural gas production systems, landfills, coal mining, animal manure, and fermentation of natural systems. Methane has 25 times the global warming potential of CO2. The figure below shows the total GHG percentages from various economic sectors. The transportation sector is the largest contributor of greenhouse gas emissions. Greenhouse gas emissions from transportation mainly result from burning fossil fuels in cars, trucks, ships, trains, and planes. Over 94% of transportation fuel is petroleum-based, including primarily gasoline and diesel, which leads to direct emissions. The transportation sector is the largest source of direct greenhouse gas emissions and ranks second when considering indirect emissions from electricity use across all sectors. Although transportation is an end-use sector for electricity, it currently accounts for a relatively small portion of total electricity consumption. Indirect emissions from electricity make up less than 1% of direct emissions in this sector. The next figure shows the emissions of various GHG emissions from 1990-2021. The EPA points out that overall emissions of CH4 have been reduced by 11% from 1990-2021. However, an article published in Nature (Yvon-Durocher, March 2014) suggests that there may be an unexpected consequence of warming temperatures; global warming can increase the amount of methane evolved from natural ecosystems. So, it remains to be seen what impacts can happen that have not been included in climate change models.

The image is a pie chart that illustrates the distribution of energy consumption across different sectors. The chart segments the total energy use into five main categories, each represented by a percentage of the whole.

The Transportation sector accounts for the largest share at 28%, indicating it is the most energy-intensive sector. This is followed by the Electric Power sector, which uses 25% of the total energy. The Industry sector comes next with 23%, reflecting significant energy use in manufacturing and production processes. The Residential & Commercial sector collectively consumes 13%, representing energy used in homes and businesses. Finally, the Agriculture sector accounts for 10% of total energy consumption.

There are several possible responses to abate CO2 and CH4: 1) do nothing; 2) reduce CO2 and CH4 prudently; 3) drastically reduce energy use; and 4) move to a carbon-free society. The easiest, but quite possibly the most damaging in the long run, is to do nothing - currently, some nations are pushing to at least increase conservation. The use of hybrids has decreased our use of gasoline, as the increase in Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards has had an impact. However, prudent measures to reduce GHG will most likely not be enough to make a huge impact. Therefore, the use of biofuels could have great potential for reducing the impact of CO2 and CH4, if done well. However, some actions in South America have shown that if switching to biofuel growth is not handled well, a greater problem can be created. Some rainforest areas were removed from South America to clear land for producing biofuels, but the rainforests that were removed were burned, putting an excessive amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. Rainforests have grown over long periods, so there was a lot of carbon stored in them - they were also places where exotic animals, plants, and insects lived, so the burning endangered the wildlife species in the rainforests. One thing to always keep in mind: whenever an action is taken in our atmosphere, there is the possibility of a negative consequence that one cannot foresee.

1.5 Assignments Overview

1.5 Assignments Overview mjg8Quiz #1

Complete Quiz #1. It contains questions that pertain to the lesson material.

1.6 Summary and Final Tasks

1.6 Summary and Final Tasks sxr133Summary

This lesson was about how using biofuels can benefit society. We looked at increasing energy demands around the world, how economically dependent we are on foreign sources of fuel, and how we don't have much control over what the prices of our fuels will be. We also explored how the growth in GHG emissions is a vital environmental concern and discussed how, without the use of biofuels, we cannot achieve significant reductions in GHG.

Lesson Objectives Review

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- explain why biofuels are a necessary part of our energy portfolio.

References

"U.S. Energy Information Administration - EIA - Independent Statistics and Analysis. EIA's Energy in Brief: How Dependent Are We on Foreign Oil?

Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Greenhouse Gases Overview. EPA. Environmental Protection Agency.

Yvon-Durocher, G., Allen, A.P., Bastviken, D., Conrad, R., Gudasz, C., St-Pierre, A., Thanh-Duc, N., del Giorgio, P.A., "Methane fluxes show consistent temperature dependence across microbial to ecosystem scales," Nature, 507, 488-491.

Questions?

If there is anything in the lesson materials that you would like to comment on, or don't quite understand, please post your thoughts and/or questions to our Throughout the Course Questions Comments discussion forum and/or set up an appointment for office hour. The discussion forum is checked regularly (Monday through Friday). While you are there, feel free to post responses to your classmates if you are able to help.

Lesson 2: Existing Fossil Fuel Technologies for Transportation

Lesson 2: Existing Fossil Fuel Technologies for Transportation mjg8Overview

In the previous lesson, we learned that alternative fuels are a viable replacement for fossil fuels. But to make them viable, the fuels must fit into the current fuel structure and needs. This week's lesson focuses on transportation fuels - we will learn some chemistry about fuels (a short chemistry tutorial is first), how these fuels are currently made, and how these fuels are utilized. This provides a basis for understanding how alternative fuels must be chemically modified, so we do not have to make significant changes in utilization.

Lesson Objectives

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- explain the chemistry of gasoline, diesel fuel, jet fuel, and fuel oil;

- describe the basics of how these fuels are made by converting from crude oil;

- discuss the utilization of these fuels in cars, trucks, aircraft, and various engine types;

- evaluate necessary fuel characteristics for various vehicle engines.

Lesson 2 Road Map

This lesson will take us one week to complete. Please refer to the Course Syllabus for specific time frames and assignment due dates.

Questions?

If there is anything in the lesson materials that you would like to comment on or don't quite understand, please post your thoughts and/or questions to our Throughout the Course Questions and Comments discussion forum. The discussion forum will be checked regularly. While you are there, feel free to post responses to your classmates if you are able to help. Regular office hours will be held to provide help for EGEE 439 students.

2.1 Chemistry Tutorial

2.1 Chemistry Tutorial ksc17The chemical compounds that are important for understanding most of the chemistry in this course are organic - that means that the compounds primarily contain carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms (also sulfur and nitrogen). They can also be called hydrocarbons. The basic structures that we will be discussing in this course are called: 1) alkane (aka aliphatic), 2) branched alkane, 3) cycloalkane, 4) alkenes (double-bonds), 5) aromatic, 6) hydroaromatic, and 7) alcohols. First, I will show the atoms and how they are connected using the element abbreviation and lines as bonds, and then I will show abbreviated structural representations.

| Name | Atoms and Bonds | Stick Representation |

|---|---|---|

| Heptane (7 C atoms) |  |  |

| Name | Atoms and Bonds | Stick Representation |

|---|---|---|

| Isobutane (4 C atoms) |  |

|

| Isopentane (5 C atoms) |  |  |

| Name | Atoms and Bonds | Stick Representation |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclohexane (6 C atoms) |  |  |

| Name | Atoms and Bonds | Stick Representation |

|---|---|---|

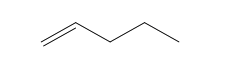

| Pentene (5 C atoms) |  |  |

| Name | Atoms and Bonds | Stick Representation |

|---|---|---|

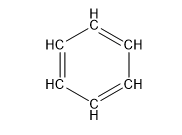

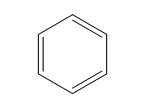

| Benzene (6 C atoms) |  |  |

| Name | Atoms and Bonds | Stick Representation |

|---|---|---|

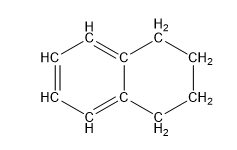

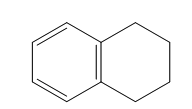

| 1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene, aka tetralin (10 C atoms) |  |  |

| Name | Atoms and Bonds | Stick Representation |

|---|---|---|

| Butanol (4 C atoms) |  |  |

| Ethanol (2 C atoms) |  |  |

The following table shows common hydrocarbons and their properties. It is important to know the properties of various hydrocarbons so that we can separate them and make chemical changes to them. This is a very brief overview - we will not yet be going into significant depth as to why the differences in chemicals affect the properties.

| Name | Number of C Atoms | Molecular Formula | bp (°C), 1 atm | mp (°C) | Density (g/mL) (@20°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | 1 | CH4 | -161.5 | -182 | -- |

| Ethane | 2 | C2H6 | -88.6 | -183 | -- |

| Propane | 3 | C3H8 | -42.1 | -188 | -- |

| Butane | 4 | C4H10 | -0.5 | -138 | -- |

| Pentane | 5 | C5H12 | 36.1 | -130 | 0.626 |

| Hexane | 6 | C6H14 | 68.7 | -95 | 0.659 |

| Heptane | 7 | C7H16 | 98.4 | -91 | 0.684 |

| Octane | 8 | C8H18 | 125.7 | -57 | 0.703 |

| Nonane | 9 | C9H20 | 150.8 | -54 | 0.718 |

| Decane | 10 | C10H22 | 174.1 | -30 | 0.730 |

| Tetradecane | 14 | C14H30 | 253.5 | 6 | 0.763 |

| Hexadecane | 16 | C16H34 | 287 | 18 | 0.770 |

| Heptadecane | 17 | C17H36 | 303 | 22 | 0.778 |

| Eicosane | 20 | C20H42 | 343 | 36.8 | 0.789 |

| Cyclohexane | 6 | C6H12 | 81 | 6.5 | 0.779 |

| Cyclopentane | 5 | C5H10 | 49 | -94 | 0.751 |

| Ethanol | 2 | C2H6O | 78 | -114 | 0.789 |

| Butanol | 4 | C4H10O | 118 | -90 | 0.810 |

| Pentene | 5 | C5H10 | 30 | -165 | 0.640 |

| Hexene | 6 | C6H12 | 63 | -140 | 0.673 |

| Benzene | 6 | C6H6 | 80.1 | 5.5 | 0.877 |

| Naphthalene | 10 | C10H8 | 218 | 80 | 1.140 |

| 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydronaphthalene | 10 | C10H12 | 207 | -35.8 | 0.970 |

2.2 Refining of Petroleum into Fuels

2.2 Refining of Petroleum into Fuels mjg8Much of the content in this particular section is based on information from Harold H. Schobert, Energy and Society: An Introduction, 2002, Taylor & Francis: New York, Chapters 19-24.

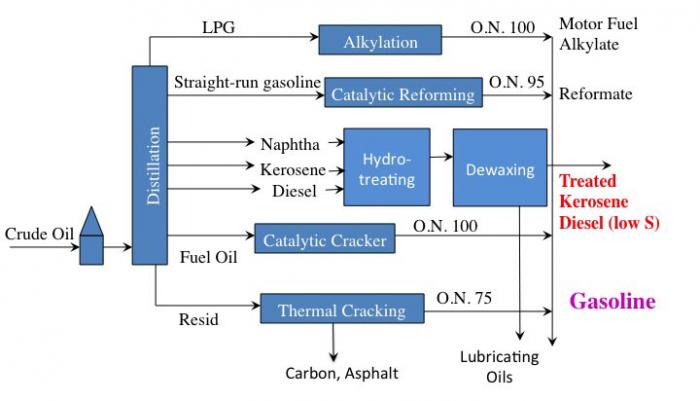

The following is a simplified flow diagram of a refinery. Since it looks relatively complicated, the diagram will be broken into pieces for better understanding.

Simple flow diagram of an oil refinery. Crude oil is the first process, and it breaks the products down into LPG, straight-run gasoline, naphtha/kerosene/diesel, fuel oil, and resid. LPG is used in the alkylation process to add carbons; straight-run gasoline is processed in a catalytic reformer to change to a branched-chain alkane; naphtha/kerosene/diesel is hydrotreated and dewaxed; fuel oil is catalytically cracked to make more gasoline, and resid is thermally cracked to make more gasoline.

Crude oil enters and goes to distillation. From distillation:

- LPG (gases) goes through alkylation to become O.N. 100 Motor Fuel Alkylate which can go on to become gasoline.

- Straight-run gasoline goes through catalytic reforming to become O.N. 95 Reformate which can go on to become gasoline.

- Naphtha, Kerosene, and Diesel all go through Hydrotreating and then dewaxing to become either treated Kerosene, Diesel (low sulfur), or lubricating oils.

- Fuel Oil goes through a catalytic cracker to become O/N 90-95 Gasoline.

- Resid goes through Thermal Cracking to become either Carbon, Asphalt, or O.N. 75 Gasoline.

Distillation

We will start with the first step in all refineries: distillation. Essentially, distillation is a process that heats crude oil and separates it into fractions. It is the most important process of a refinery. Crude oil is heated, vaporized, fed into a column that has plates in it, and the materials are separated based on the boiling point. It indicates that as the liquids are separated, the top-end materials are gases and lighter liquids, but as you go down the column, the products have a higher boiling point, the molecular size gets bigger, the flow of the materials gets thicker (i.e., increasing viscosity), and the sulfur (S) content typically stays with the heavier materials. Notice we are not using the chemical names, but the common mixture of chemicals. Gasoline represents the carbon range of ~ C5-C8, naphtha/kerosene (aka jet fuel) C8-C12, diesel C10-C15, etc. As we discuss the refinery, we will also discuss the important properties of each fuel.

The most important product in the refinery is gasoline. Consumer demand requires that 45-50 barrels per 100 barrels of crude oil processed are gasoline. The issues for consumers are, then: 1) quality suitability of gasoline and 2) quantity suitability. The engine that was developed to use gasoline is known as the Otto engine. It contains a four-stroke piston (and engines typically have 4-8 pistons). The first stroke is the intake stroke - a valve opens, allows a certain amount of gasoline and air, and the piston moves down. The second stroke is the compression stroke - the piston moves up and valves close so that the gasoline and air that came in the piston during the first stroke are compressed. The third stroke happens because the spark plug ignites the gasoline/air mixture, pushing the piston down. The fourth stroke is the exhaust stroke, where the exhaust valve opens and the piston moves back up. There is a good animation in How Stuff Works (Brain, Marshall. 'How Car Engines Work' 05 April 2000. HowStuffWorks.com).

Trends for products of the initial distillation

The image is a diagram of a distillation column used in the fractional distillation of crude oil, a key process in petroleum refining. The column is vertically oriented and segmented into several horizontal layers, each representing a different fraction collected during the distillation process. These fractions are separated based on their boiling points and other physical properties.

From Top to Bottom, the Fractions Are:

- Gases – The lightest and most volatile components, collected at the top.

- Gasoline – A light fuel used primarily in internal combustion engines.

- Naphtha – A volatile, flammable liquid used as a feedstock in petrochemical production.

- Kerosene – A heavier fuel used in jet engines and heating.

- Diesel – A mid-weight fuel used in diesel engines.

- Heating Oils – Heavier oils used for industrial heating and power generation.

- Resid – The heaviest fraction, often used for asphalt or further processing.

Accompanying Annotations:

To the right of the column, a vertical arrow points downward, indicating a gradient of physical properties as one moves down the column:

- Boiling Point (B.P) increases

- Molecular Size increases

- Viscosity increases

- Sulfur Content (S content) usually increases

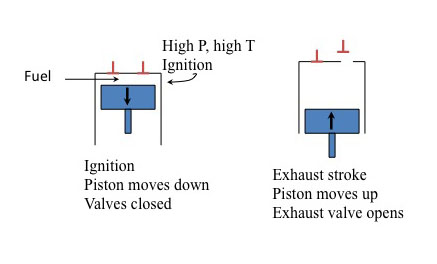

Four strokes of Otto gasoline engine

The diagram is divided into four vertical sections, each representing one of the four strokes in the engine cycle. Each section includes a labeled piston within a cylinder, directional arrows indicating piston movement, and annotations describing valve positions and actions.

Four strokes of Otto gasoline engine

- Intake stroke. The piston moves down. The intake valve opens.

- Compression stroke. The piston moves up. The valves close.

- Power stroke. The piston moves down. The valves closed.

- Exhaust stroke. The piston moves up. The exhaust valve opens.

You'll notice the x and the y on strokes 1 and 2. The ratio of x/y is known as the compression ratio (CR). This is a key design feature of an automobile engine. Typically, the higher the CR, the more powerful the engine is and the higher the top speed. The "action" is in the ignition or power stroke. The pressure in the cylinder is determined by 1) pressure at the moment of ignition (determined by CR) and 2) a further increase in pressure at the instant of ignition. At higher pressures with the CR, the more likely the pressure will cause autoignition (or spontaneous ignition), which can cause "knocking" in the engine - the higher the CR, the more likely the engine will knock. This is where fuel quality comes in.

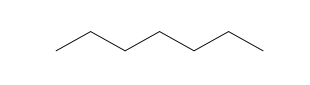

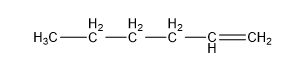

For gasoline engines, the CR can be adjusted to the fuel rating to prevent knocking; this fuel quality is known as the "octane" number. Remember the straight-chain alkanes in the chemistry tutorial? The straight-chain alkanes are prone to knocking. The branched alkanes are not. The octane number is defined as 1) heptane - octane number equal to 0, and 2) 2,2,4-trimethylpentane - octane number equal to 100 (this is also known as "octane"). See the figure below for the chemical structures of heptane and octane for octane numbers. Modern car engines require an 87, 89, or 93-94 octane number. However, when processing crude oil, even high-quality crude oil, we can only produce from a distillation yield of 20% with an octane number of 50. This is why crude oil needs to be processed, to produce gasoline at 50% yield with an octane number of 87-94.

Other ways to improve the octane number:

- Add aromatics. Aromatics have an octane number (ON) greater than 100. They can be deliberately blended into gasoline to improve ON. However, many aromatic compounds are suspected carcinogens, so there are regulatory limits on the aromatic content in gasoline.

- Another approach to increasing ON is to add alcohol groups. Methanol and ethanol are typical alcohols that can be added to fuel. ON is ~110. They can be used as blends with racing cars (known as "alky").

But even with these compounds, distillation will not produce enough gasoline with a high enough ON. So other processes are needed.

"Cracking" Processes

Thermal cracking

One way to improve gasoline yield is to break the bigger molecules into smaller molecules - molecules that boil in the gasoline range. One way to do this is with "thermal cracking." Carbon Petroleum Dubbs was one of the inventors of a successful thermal cracking process. The process produces more gasoline, but the ON was still only ~70-73, so the quality was not adequate.

Catalytic cracking

Eugene Houdry developed another process; in the late 1930s, he discovered that thermal cracking performed in the presence of clay minerals would increase the reaction rate (i.e., make it faster) and produce molecules that had a higher ON, ~100. The clay does not become part of the gasoline - it just provides an active surface for cracking and changing the shape of molecules. The clay is known as a "catalyst," which is a substance that changes the course of a chemical reaction without being consumed. This process is called "catalytic cracking". The figure below shows the reactants and products for reducing the hexadecane molecule using both reactions. Catalytic cracking is the second most important process of a refinery, next to distillation. This process enables the production of ~45% gasoline with higher ON.

Below is the refining schematic with the additional processing added.

There are also tradeoffs when refineries make decisions as to the amount of each product they make. The quality of gasoline changes from summer to winter, as well as with gasoline demand. Prices that affect the quality of gasoline include 1) the price of crude oil, 2) the supply/demand of gasoline, 3) local, state, and federal taxes, and 4) the distribution of fuel (i.e., the cost of transporting fuel to various locations). Below is a schematic of how these contribute to the cost of gasoline and diesel.

Additional Processes

Alkylation

The alkylation process takes the small molecules produced during distillation and cracking and adds them to medium-sized molecules. They are typically added in a branched way in order to boost ON. An example of adding methane and ethane to butane is shown below.

Catalytic Reforming

A molecule may be of the correct number of carbon atoms but need a configuration that will either boost ON or make another product. The example below shows how reforming n-octane can produce 3,4-dimethyl hexane.

![]()

So, let's add these two new processes to our schematic in order to see how they fit into the refinery, and how this can change the ON of gasoline. The figure below shows the additions, as well as adding in the middle distillate fraction names. Typically, naphtha and kerosene, which can also be sold as these products, are the products that make up jet fuels. So, our next topic will cover how jet engines are different from gasoline engines and use different fuel.

Refining of crude oil into gasoline with additional processes of alkylation and catalytic reforming.

This is a simple flow diagram of a crude oil refinery.

Crude oil enters and goes to distillation. From distillation:

LPG (gases) goes through alkylation to become O.N. 100 Motor Fuel Alkylate which can go on to become gasoline

Straight-run gasoline goes through catalytic reforming to become O.N. 95 Reformate which can go on to become gasoline

Naphtha, Kerosene, and Diesel become jet fuels.

Fuel Oil goes through a catalytic cracker to become O.N 90-95 Gasoline

Resid goes through Thermal Cracking to O.N. 75 Gasoline.

2.3 Jet Engines

2.3 Jet Engines mjg8The first aircraft used engines similar to the Otto four-stroke cycle, reciprocating piston engines. The Wright Flyer was an aircraft with this type of engine. During WWII, powerful 16-cylinder, high-compression ratio reciprocating engines were developed. However, the military was interested in developing engines that would make airplanes go faster, higher, and farther - this was to reduce the length of flights and provide better international communication. In order to achieve high-speed flight, a dilemma ensued: 1) the atmosphere thins at high altitudes, offering less air resistance to a plane which could lead to higher speeds, but 2) in "thinner" air, it is more difficult to get combustion air into the conventional piston engine. The modern jet engine was developed as part of a term paper by Frank Whittle while at the British Royal Air Force College, covering the fundamental principles of jet propulsion aircraft.

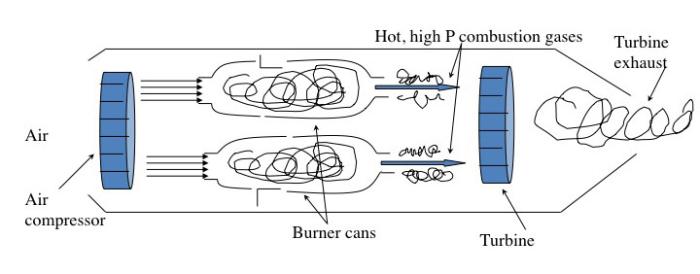

The jet engine begins with a "burner can," where jet fuel is injected and combusted in high-pressure air. The combustion produces a stream of high-temperature, high-pressure gases, as shown in the first figure below. If more power is required, two to four-burner cans can be included, and the high-temperature, high-pressure combustion gases operate a turbine (more about turbines for electricity generation in the lesson on electricity). The second figure depicts these additions. In the third figure, a containment vessel is put around the burner cans; the gases that exit the turbine pass through a nozzle. The gases exiting the nozzle provide thrust for the airplane. The fourth figure shows the completed engine - the high-pressure air comes from the air compressor, which is operated by the turbine.

There are variations on a simplistic jet engine: 1) the fan jet (turbofan), 2) the prop jet (turboprop), and 3) the turboshaft. The fan jet has a large fan in front of the engine to help provide air to the air compressor. It is a little slower than a turbojet but more fuel-efficient. This is the type favored for civilian transport aircraft. The prop jet uses the mechanical work of the turbine to operate a propeller. These types of engines are typically used for commuter aircraft. The turboshaft is a gas turbine engine that uses all of the output of the turbine to turn the blades, without jet exhaust. Helicopters, tanks, and hovercrafts use these types of engines. So, what is the fuel for jets?

Jet Fuel

Conventional jet fuel is composed primarily of straight-run kerosene (straight-chain carbons and accompanying hydrogen, bigger molecules than gasoline). However, there are some purification steps that are needed to ensure that the fuel behaves in jet engines.

The first step is the removal of sulfur. When sulfur is burned, it forms sulfur oxide compounds, such as sulfur dioxide (SO2) and sulfur trioxide (SO3). Because there are multiple sulfur oxide compounds, they are abbreviated into one chemical formula of SOx. These compounds, when combined with water, form acid rain (more on this in the next lesson on coal for electricity generation). Sulfur compounds are corrosive to fuel systems and have noxious odors. Sulfur is removed by reacting it with hydrogen and a metal catalyst; the processes are known as hydrogen desulfurization processes (HDS) and produce H2S (hydrogen sulfide), which is then reacted to solid sulfur.

Another problem that can occur with jet fuel is if it contains too much aromatic compound content. A small amount is actually necessary to lubricate gaskets and O-rings. However, aromatics are suspected carcinogens, and in combustion, aromatics are precursors to smoke and soot. Too much aromatic content can cause problems such as 1) poor aesthetics, 2) carcinogens, and 3) tracking of military aircraft. The way to remove aromatic compounds is the same as for removing sulfur; the aromatic compound is reacted with hydrogen and a metal catalyst to add hydrogen to the aromatic ring. The resulting compounds are heteroaromatics and cycloalkanes.

Another problem that can occur in the middle distillate fractions can occur if the fuel contains waxes. Waxes are higher molecular weight alkane hydrocarbons that can be dissolved in kerosene. At very cold temperatures at high altitudes, wax can either separate as a solid phase or cause the fuel to freeze and cause plugging in the fuel lines. This can also cause a problem called low-temperature viscosity. Viscosity is a measurement of the flow of a fluid; the thicker the fluid gets (and flow is reduced), the higher the viscosity. While the fuel isn't frozen, it is flowing slower and could cause problems for the engine. Again, the reason for the increase in viscosity is similar to having waxes in the kerosene; high viscosity is caused by bigger molecules within the fuel. The way to improve jet fuel properties is to remove the larger molecules. This is called dewaxing.

The last problem we will discuss has to do with nitrogen. Jet fuels do not typically contain nitrogen, but when combusting fuel using air (which contains primarily nitrogen), nitrogen oxide compounds can form, shown as a formula NOx. Because jet engines burn fuels at high temperatures, thermal NOx is a problem. NOx will contribute to acid rain. If there is any nitrogen in the fuel, it would be removed during the removal of sulfur.

A refinery will make ~10% of its product as jet fuel. The Air Force uses 10% of that fuel, so about 1% of refinery output is for military jet fuel. The figure below shows the additional processes just discussed in our schematic.

Primary processes that are typical in a petroleum refinery.

This is a simple flow diagram of a crude oil refinery.

Crude oil enters and goes to distillation. From distillation:

LPG (gases) goes through alkylation to become O.N. 100 Motor Fuel Alkylate which can go on to become gasoline

Straight-run gasoline goes through catalytic reforming to become O.N. 95 Reformate which can go on to become gasoline

Naphtha, Kerosene, and Diesel all go through Hydrotreating and then dewaxing to become either treated Kerosene, Diesel (low sulfur) or lubricating oils.

Fuel Oil goes through a catalytic cracker to become O/N 90-95 Gasoline

Resid goes through Thermal Cracking to become either Carbon, Asphalt, or O.N. 75 Gasoline.

2.4 Diesel Engines

2.4 Diesel Engines sxr133Rudolf Diesel first developed Diesel engines in the 19th century. He did so because he wanted to develop an engine that was more efficient than an Otto engine and that could use poorer quality fuel than gasoline. The Diesel engine also operates on a four-stroke cycle, but there are some important differences. Diesel engines have a high compression ratio (CR)- a small Diesel engine has a CR of 13:1, while a high-performance Otto engine has a CR of 10:1. Upon the compression stroke (stroke 2), there is a high increase in temperature and pressure. In the third stroke, fuel is injected and it ignites because of the high temperature and pressure of the compressed air. You can see an animation of this at How Stuff Works (Brain, Marshall. 'How Diesel Engines Work' 01 April 2000. HowStuffWorks.com). Diesel engines use fuel more efficiently; and under comparable conditions, a Diesel engine will always get better fuel efficiency than a gasoline Otto engine. Essentially, Diesel engines operate by knocking. The continuous knocking has two consequences: 1) a Diesel engine must be more sturdily built than a gasoline engine, so it is heavier and has a longer life - 300,000-350,000 miles before major engine service, and 2) fuel standards are "backward" from that of gasoline; we want fuel to knock.

Diesel Fuel

Diesel fuel has a much higher boiling range than gasoline. The molecules are larger than gasoline, and the octane scale cannot be used as a guide. The scale that is used for diesel fuel is called the cetane number. The compound, cetane, or hexadecane, C16H34, is the standard where the cetane number is 100. For the cetane number 0 (the other end of the scale), the chemical compound used is methylnaphthalene, an aromatic compound that doesn't knock. Most diesel fuels will have cetane numbers of 40-55, with the value in Europe on the higher end and the value in the US at the lower end of that range. In a refinery, diesel fuels are processed in the same fashion as jet fuels, using hydrogenation reactions to remove sulfur and nitrogen and reacting aromatics to hydro aromatics and cycloalkanes. Dewaxing also must be done to improve viscosity and low-temperature problems, particularly in colder climates. Therefore, the primary processes that are typical in a petroleum refinery apply to diesel fuel as well as jet fuel. Except in airplanes, diesel engines dominate internal combustion engine applications. They are standard for large trucks; dominate railways in North America and other countries; are common in buses; and are adapted in small cars and trucks, particularly in Europe.

Similar to gasoline, prices that affect the quality of diesel include 1) the price of crude oil, 2) the supply/demand of diesel, 3) local, state, and federal taxes, and 4) the distribution of fuel (i.e., the cost of transporting fuel to various locations). Above is a schematic of how these contribute to the cost of diesel.

2.5 Assignments Overview

2.5 Assignments Overview mjg8Quiz #2

Complete Quiz #2. It contains questions that pertain to the lesson material.

2.6 Summary and Final Tasks

2.6 Summary and Final Tasks sxr133Summary

This lesson was a very brief overview - there are entire classes based on this one lecture. In this lesson, we discussed the different transportation engines for vehicles, the fuels used for these vehicles, and how the fuels are produced from a refinery. Gasoline is the lighter fuel used in typical automobile engines, while diesel fuel is used in Diesel engines. Diesel engines get better fuel mileage than gasoline engines - gasoline is lighter than diesel. Here in the US, the primary fuel produced is gasoline (~45-50%).

Lesson Objectives Review

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- explain the chemistry of gasoline, diesel fuel, jet fuel, and fuel oil.

- describe the basics of how these fuels are made by converting from crude oil.

- discuss the utilization of these fuels in cars, trucks, aircraft, and various engine types.

- evaluate necessary fuel characteristics for various vehicle engines.

Questions?

If there is anything in the lesson materials that you would like to comment on, or don't quite understand, please post your thoughts and/or questions to our Throughout the Course Questions Comments discussion forum and/or set up an appointment during office hours. The discussion forum is checked regularly (Monday through Friday). While you are there, feel free to post responses to your classmates if you can help.

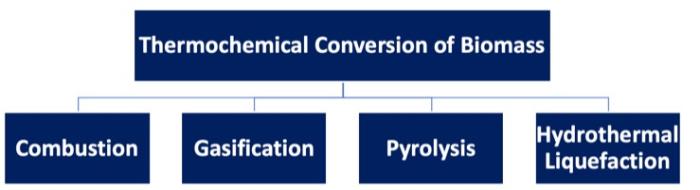

Lesson 3: Use of Biomass in Thermal Technologies

Lesson 3: Use of Biomass in Thermal Technologies sxr133Overview

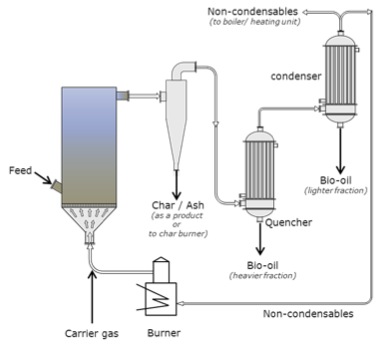

In the last few lessons, we’ve learned about why current society is considering the use of biomass and the current methods of generating transportation fuels and electricity from fossil sources. With this lesson, we are moving into the use of biomass in various ways. This lesson focuses on thermal processes (both to generate electricity and liquid fuels), using biomass rather than coal, petroleum, or natural gas. Different fuels are produced from gasification and pyrolysis, so we will determine how each must be processed and utilized for fuel.

Lesson Objectives

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- explain how wood was used historically to produce heat and electricity;

- evaluate the difference between combustion and gasification, and explain how design features differ depending on the process;

- evaluate how pyrolysis is different from gasification;

- describe the utilization of products from gasification versus pyrolysis, including how the processing of products differs.

Lesson 3 Road Map

This lesson will take us one week to complete. Please refer to the Course Syllabus for specific time frames and assignment due dates.

Questions?

If there is anything in the lesson materials that you would like to comment on or don't quite understand, please post your thoughts and/or questions to our Throughout the Course Questions and Comments discussion forum. The discussion forum will be checked regularly. While you are there, feel free to post responses to your classmates if you are able to help. Regular office hours will be held to provide help for EGEE 439 students.

3.1 Wood

3.1 Wood ksc17History of Burning Wood

Wood has been used as a source of energy for thousands of years (the first known use of fire was determined when archeologists made discoveries of humans living 400,000 years ago), and wood was the obvious source to make fire. In the Americas, in 1637, the people of Boston suffered from the scarcity of wood. It became America’s first energy crisis after less than one century of settlement. During the late 1700s, Benjamin Franklin invented a cast iron stove for indoor use. It held heat in the room after the fire burned out. However, it had a design flaw in that it had no way to pull in air, so fires went out quickly. So David R. Rittenhouse added a chimney and exhaust pipe to improve upon it.

Burning Wood

First, we will look at where energy is stored in materials, starting with the methane molecule. The combustion of methane is exothermic (releases heat as the reaction proceeds), but the reaction must be initiated before it will sustain itself with the continued availability of methane and oxygen. The formula below shows the reaction in a stoichiometric format:

The figure below shows the same reactants and products, but with the bonds before reaction and after the reaction, on a molecular/atomic level. The number of atoms in each molecule doesn't change, but how they are arranged and connected does. The only real change is how the atoms are linked - these are the chemical bonds. Since ENERGY comes out of a burning system, then it must mean that more energy is stored in 4 C-H bonds and 2 O-O bonds than in 4 H-O and two C-O bonds. The ENERGY released during chemical combustion comes from ENERGY stored in chemical bonds of fuel & oxygen.

The 1 Methane and 2 oxygen reaction shows bond connections before and after the combustion reaction.

Reactants: Methane will react with two oxygen molecules. All of the four hydrogens in methane are connected to a single carbon atom by 4 single bonds. The oxygen molecules are each two oxygen atoms connected by a double bond.

During combustion, the atoms rearrange and form new bonds.

Products: The carbon atom connects to 2 oxygen atoms with a double bond between the carbon and each oxygen to produce one carbon dioxide molecule. Additionally, each of the other remaining oxygen atoms forms 2 single bonds to 2 of the remaining hydrogen atoms to form a water molecule. The net products of the reaction are 1 CO2 molecule and 2H2O molecules.

We now know the reaction chemistry of methane combustion, but wood is a much more complex material than methane. Wood contains up to 50% water. Water in the wood will reduce the heating value of the wood, and if the wood is very wet, it will lead to a smoky fire. The main components of wood (we will cover this in more depth in a later lesson) are cellulose (what paper is made from) and lignin (the part of a tree that makes it have a sturdy structure). In order to start a fire, you typically must ignite a material that burns easily to begin heating the wood (this can be newspaper or a “fire starter”). The components begin to decompose from the heat (therefore we are not technically “burning” yet), which produces vapors and char. The vapors are called “volatiles” and the char is composed of carbon and ash. The volatiles are what actually begin to burn, producing a flame. The carbon-rich char produces glowing embers or “coals,” which are needed to keep the fire sustained. Wood does not typically contain sulfur, so no sulfur oxides (or SOx) are produced.

There can be problems with burning wood. The smoke comes from particulates that did not burn or only partially burned which can pollute the atmosphere, and typically come from resins in the trees. It isn’t an issue when one or two people are burning wood, but when thousands of people burn wood in fireplaces. In State College, Pennsylvania, in the winter, one can see smoke in the air from fireplaces. Wood fires in fireplaces can also deposit soot and creosote in the chimneys, which if not cleaned periodically, can ignite. Burning wood (or really most things) will produce an ash material (minerals in wood and coal that react with air under combustion conditions); the ash must be disposed of. Wood smoke also contains a variety of chemicals that can be carcinogenic.

Now let’s begin discussing different biomass sources, how we measure different properties of different biomasses, and how to determine the atomic composition of biomass.

3.2 Biomass

3.2 Biomass sxr133There are four types of biomass resources that can be utilized:

- agricultural residues

- energy crops

- forestry residues

- processing wastes

Examples of different sources are listed below:

Agricultural Residues:

- Corn stover

- Wheat straw

- Rice straw

- Soybean stalk

Energy Crops:

- Switchgrass

- Sweet sorghum

- Sugar canes

- Algae

- Cattail

- Duckweed

Forestry Residues:

- Saw dust

- Woody chips

Processing wastes:

- Food processing wastes

- Animal wastes

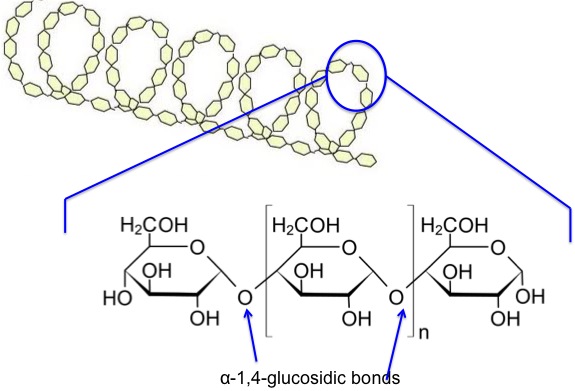

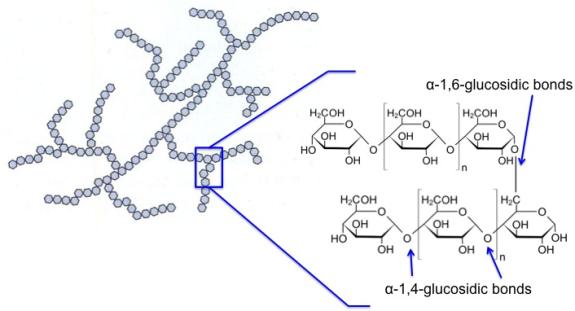

- Municipal solid wastes

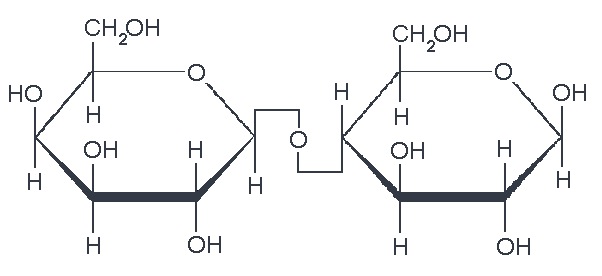

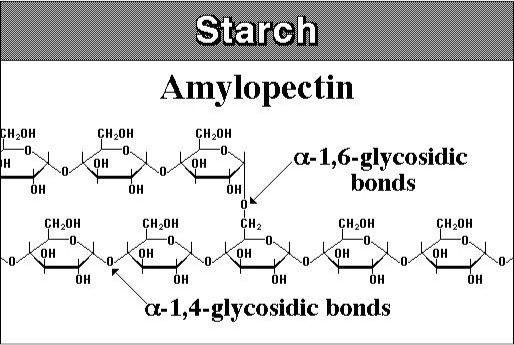

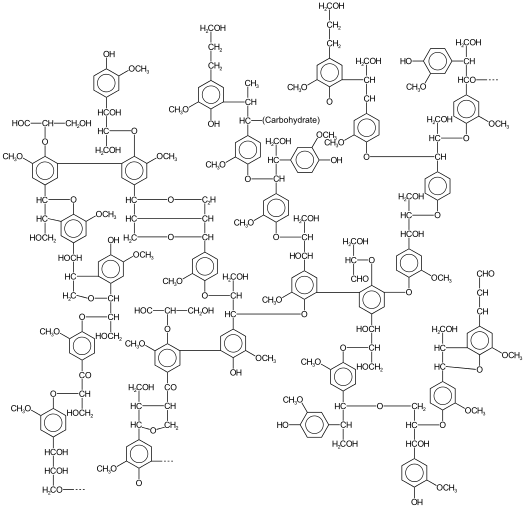

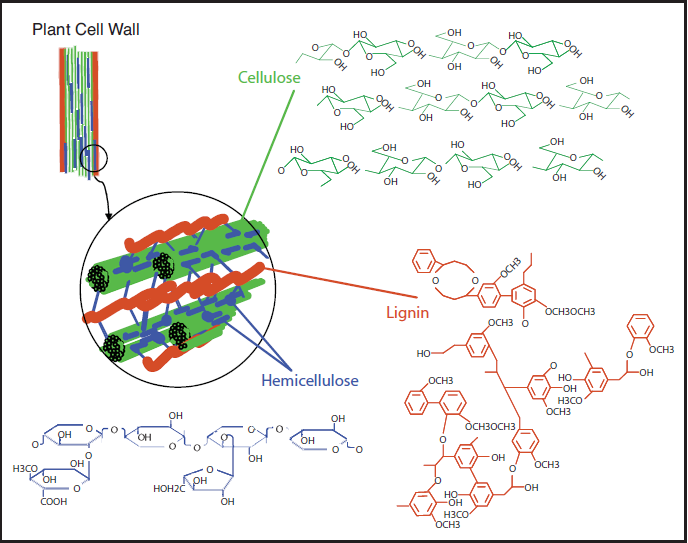

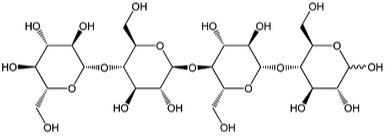

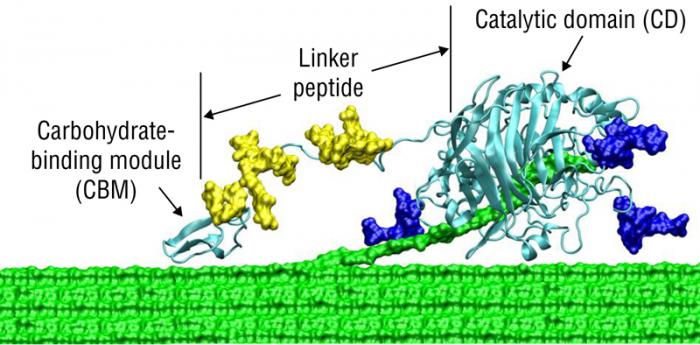

As already mentioned, most biomass is at least partially composed of three components: cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. The figures below show a diagram of lignocellulose and the biomass broken down into three parts. There will be significantly more discussion on biomass composition in future lessons. Cellulose is a crystalline polymer of ring molecules (6 carbons) with OH and COOH groups (in the first figure below, cellulose is the straight green lines; in the second figure it is the green molecule). Hemicellulose is similar, but has ring molecules with 5 and 6 carbons, and is amorphous in structures, as depicted in the first figure below by the black squiggly line; The second figure shows how it is around the cellulose and more detail of the molecular structure. Lignin is the material that holds it all together and is the light blue line in the first figure below and it is in red in the second figure.

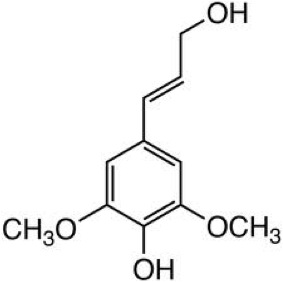

The image is a detailed scientific diagram illustrating the biomass and its three primary components: cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. On the left side, the plant cell wall is shown in a magnified view, revealing how these components are arranged within the wall's matrix.

Cellulose is represented in green and is shown as long, linear chains that form microfibrils, providing structural strength. Its chemical structure is displayed in the top right corner of the image.

Hemicellulose is depicted in blue and appears as shorter, branched polysaccharides that interact with cellulose fibers, helping to cross-link the cell wall components. Its chemical structure is shown in the bottom left corner.

Lignin is illustrated in red and is shown filling the spaces between cellulose and hemicellulose, adding rigidity and resistance to degradation. Its complex, aromatic chemical structure is displayed in the bottom right corner.

How To Determine Properties of Biomass

There are four common ways to measure the properties of any carbon product, which will also be used for biomass: 1) proximate analysis, 2) ultimate analysis, 3) heat of combustion, and 4) ash analysis.

Proximate analysis

Proximate analysis is a broad measurement to determine the moisture content (M), volatile matter content (VM), fixed carbon content (FC), and ash content. These are all done on a mass basis, typically, and are done in what is called a proximate analyzer – the analyzer just measures the mass loss at certain temperatures. Moisture is driven off at ~105-110°C (just above the boiling point of water); it represents physically bound water only. Volatile matter is driven off in an inert atmosphere at 950°C, using a slow heating rate. The ash content is determined by taking the remaining material (after VM loss) and burning it at above 700°C in oxygen. The fixed carbon is then determined by the difference: FC = 1 – M – Ash – VM.

The following is an example of proximate analysis of lignin, which is part of wood and/or grasses, primarily:

- Moisture (wt%): 5.34

- Ash (wt%): 14.05

- Volatile Matter (wt%): 60.86

Sometimes the moisture content will be removed from the VM and ash contents, on a dry basis:

Ultimate analysis

The ultimate analysis is more specific in that it analyzes the elemental composition of the organic portion of materials. The compositions of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), nitrogen (N), sulfur (S), and oxygen (O) are determined on a mass percent basis and can be converted to an atomic basis. In some cases, chlorine (Cl) will also be analyzed. There are instruments that are designed to measure only the C H N mass percent and then another to measure the S percent; the instrument combusts the material and measures the products of combustion. The following is an example problem for determining the molecular atomic composition of biomass when being provided with an ultimate analysis. Oxygen is usually determined by difference. Water can skew the hydrogen results and must be accounted for.

Your Turn

Problem 1:

The ultimate analysis shows that the C, H, O, N, and S contents of a biomass material are 51.9%, 5.5%, 41.5%, 0.8%, and 0.3% on a dry basis. What is the chemical formula of this biomass? How many kilograms of air are required to completely combust 1 kg of this biomass? The results are shown below.

The following examples are of the calculation of Problem 1, the chemical formula of biomass, when given mass percent on a dry basis. If you know the elemental mass percent of the sample, you can divide it by the molecular weight to determine the atomic value of each element. The values in the table are then divided by the atomic number of carbon to normalize the molecule. So, for every carbon, you have 1.26 atoms of hydrogen, 0.6 atoms of oxygen, etc.

| Values | |

|---|---|

Heat of combustion

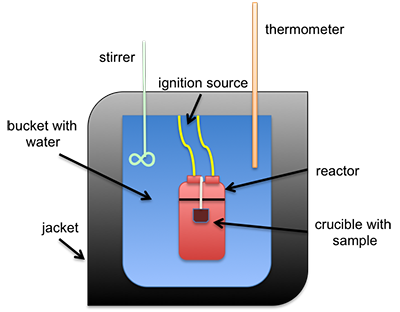

The heat of combustion can be measured directly using a bomb calorimeter. This instrument is used to measure the calorific value per mass (calorie/gram or Btu/lb). It can also be estimated using different formulas that calculate it based on either ultimate or proximate analysis. A common type of calorimeter is the isoperibol calorimeter, which will contain the heat inside the jacket but will accommodate the change in temperature of the water in the bucket; see the schematic below. A sample is placed in a crucible that is put inside of a reactor with high-pressure oxygen. The sample is connected to a fuse and electrical leads that will ignite the sample, all contained within the reactor (sometimes called a bomb calorimeter). The water temperature in the bucket is measured before and after ignition, and with all the other parts calibrated, the specific heat of the water and the change in temperature are used to determine the heat of combustion.

Schematic of isoperibol calorimeter.

This is a schematic of an isoperibol calorimeter. There is a crucible containing a sample. Both sit inside a reactor. The reactor itself is in a bucket with water that has an insulating jacket on the outside, including the top. Sticking into the water are a stirrer and a thermometer. The reaction is started by an ignition source connected to the reactor.

The heating value is determined in a bomb calorimeter. Heating values are reported on both wet and dry fuel bases. For the high heating value (HHV), the value can be determined by normalizing out the moisture in a liquid form. For the low heating value (LHV), a portion of the heat of combustion is used to evaporate the moisture.

Ash Analysis

The minerals in the material, once combusted, turn to ash. The ash can be analyzed for specific compounds that will contain oxygen, such as CaO, K2O, Na2O, MgO, SiO2, Fe2O3, P2O5, SO3, and Cl. The original minerals can also be measured. Once the mineral or ash is isolated, it often must be dissolved in various acids and then analyzed. There is other instrumentation available, but the analysis is quite complicated and not often done.

Bulk density is also determined for biomass as a property. It is typically determined by measuring the weight of material per unit volume. It is usually determined on a dry weight basis (moisture-free) or on an as-received basis with moisture content available. For biomass, the low values (grain straws and shavings) are 150-200 kg/m3 (0.15-0.20 g/cm3), and the high values (solid wood) are 600-900 kg/m3 (0.60-0.90 g/cm3). The heating value and bulk density are used to determine the energy density. The figure below shows a comparison of various biomass sources to fossil fuel sources on an energy density mass basis.

Many of the fuel characteristics we have been discussing need to be known for the proper use of biomass in combustion, gasification, and other reaction chemistry.

3.3 Gasification

3.3 Gasification sxr133Now, we will go into gasification and compare it to combustion. Gasification is a process that produces syngas, a gaseous mixture of CO, CO2, H2, and CH4, from carbonaceous materials at high temperatures (750 – 1100°C). Gasification is a partial oxidation process; the reaction takes place with a limited amount of oxygen. The overall process is endothermic (requires heat to keep the reaction going), so it requires either the simultaneous burning of part of the fuel or the delivery of an external source of heat to drive the process.

Historically, gasification was used in the early 1800s to produce lighting, in London, England (1807) and Baltimore, Maryland (1816). It was manufactured from the gasification of coal. Gasification of coal, combined with Fischer-Tropsch synthesis was one method that was used during WWII to produce liquid fuel for Germany because they did not have access to oil for fuel. It has also been used to convert coal and heavy oil into hydrogen for the production of ammonia and urea-based fertilizers. As a process, it continues to be used in South Africa as a source of liquid fuels (gasification followed by Fischer-Tropsch synthesis).

Gasification typically takes place at temperatures from 750-1100°C. It will break apart biomass (or any carbon material), and usually, an oxidizing agent is added in insufficient quantities. The products are typically gas under these conditions, and the product slate will vary depending on the oxidizing agent. The products are typically hydrogen, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and methane. There may also be some liquid products depending on the conditions used. Gasification and combustion have some similarities; the figure below shows the variation in products between gasification and combustion. The table shows a comparison of the conditions.

| Specification | Combustion | Gasification |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Use | Uses excess | Uses limited amounts |

| Process Type | Exothermic | Endothermic |

| Product | Heat | Combustible Synthesis |

Zones of Gasification

There are several zones that the carbon material passes through as it proceeds through the gasifier:

- drying

- pyrolysis

- combustion

- reduction

The schematic below shows the zones and the products that typically occur during that part of the process. First, we will discuss what happens in each zone. We will also be looking at different gasifier designs to show these zones change depending on the design, and each design has advantages and disadvantages.

The drying process is essential to remove surface water, and the “product” is water. Water can be removed by filtration, evaporation, or a combination of both. Typically, waste heat is used to do the evaporation.

General schematic of different regions in a gasifier.

Diagram showing different regions and products in a gasifier. Heat is applied to the entire system, oxidizing agents such as air, O2, H2O, and CO2 enter from the bottom and biomass enters from the top.

The biomass first goes through drying which removes water. It then goes through pyrolysis which produces char, tar, and methane. From pyrolysis, the biomass can go to reduction or combustion which produces carbon dioxide and water. If the biomass goes through combustion it also then goes to reduction which produces hydrogen gas and carbon monoxide.

Pyrolysis is typically the next zone. If you look at it as a reaction:

where x is the mass fraction of tars in the volatiles. Volatile gases are released from the dry biomass at temperatures ranging up to about 700oC. These gases are non-condensable vapors such as CH4, CO, CO2, and H2 and condensable vapor of tar at the ambient temperature. The solid residues are char and ash. A typical method to test how well a biomass material will pyrolyze is thermogravimetric analysis; it is similar to the proximate analysis. However, the heating rate and oxidizing agent can be varied, and the instrument can be used to determine the optimum temperature of pyrolysis.

Gasification Process and Chemistry: Combustion and Reduction

A limited amount of oxidizing agent is used during gasification to partially oxidize the pyrolysis products of char (C), tar, and gas to form a gaseous mixture of syngas mainly containing CO, H2, CH4, and CO2. Common gasifying agents are air, O2, H2O, and CO2. If air or oxygen is used as a gasifying agent, partial combustion of biomass can supply heat for the endothermic reactions.

Combustion of gases:

The equivalence ratio (ER) is the ratio of O2 required for gasification, to O2 required for full combustion of biomass. The value of ER is usually 0.2 - 0.4. At too high ER values, excess air causes unnecessary combustion of biomass and dilutes the syngas. At too low ER values, the partial combustion of biomass does not provide enough oxygen and heat for gasification.

There are several reactions that can take place in the reduction zone. There are three possible types of reactions: 1) solid-gas reactions, 2) tar-gas reactions, and 3) gas-gas reactions. Essentially, H2O and CO2 are used as gasifying agents to increase the H2 and CO yields. The double-sided arrow represents that these reactions are reversible depending on the conditions used.

Solid-gas reactions include:

Tar-gas reactions include:

Gas-gas reactions include:

The reactions can be affected by reaction equilibrium and kinetics. For a long reaction time: 1) chemical equilibrium is attained, 2) products are limited to CO, CO2, H2, and CH4, and 3) low temperatures and high pressures favor the formation of CH4, whereas high temperatures and low pressures favor the formation of H2 and CO. For a short reaction time: 1) chemical equilibrium is not attained, 2) products contain light hydrocarbons as well as up to 10 wt% heavy hydrocarbons (tar), and 3) steam injection and catalysts can shift the products toward lower molecular weight compounds.

Gasifier Designs

There are several types of gasifier designs:

- updraft

- downdraft

- cross downdraft

- fluidized bed

- plasma

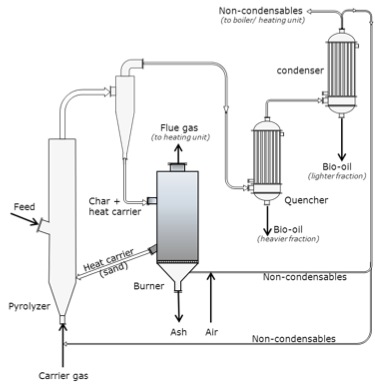

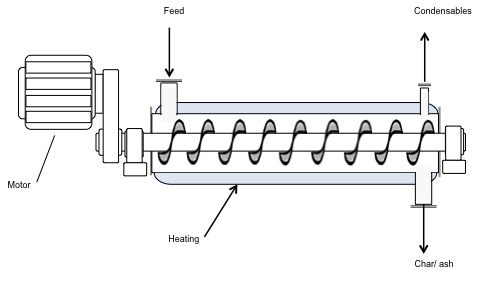

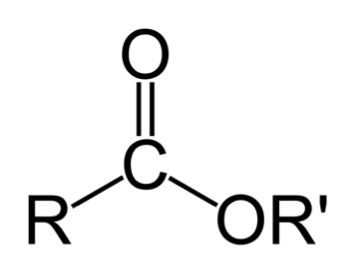

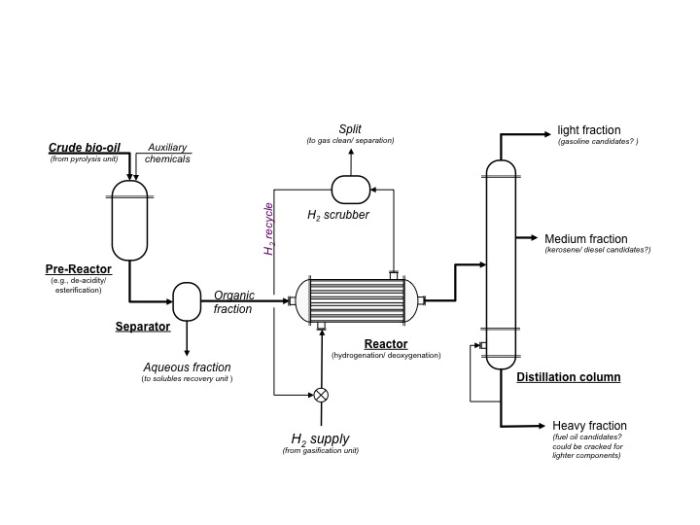

The first type of gasifier is the updraft design. The advantages include that it is a simple design and is not sensitive to fuel selection. However, disadvantages include a long start-up time, production of high concentrations of tar, and a general lack of suitability for modern heat and power systems.