5.3 Enzymatic Biochemistry and Processing

5.3 Enzymatic Biochemistry and Processing djn12Starches are broken down by enzymes known as amylases; our saliva contains amylase, so this is how starches begin to be broken down in our body. Amylases have also been isolated and used to depolymerize starch for making alcohol, i.e., yeast for bread making and for alcohol manufacturing. Chemically, the amylase breaks the carbon-oxygen linkage on the chains (α-1,4-glucosidic bond and the α-1,6-glucosidic bond), which is known as hydrolysis. Once the glucose is formed, then fermentation can take place to break the glucose down into alcohols and CO2. The amylases were isolated and the hydrolysis of glucose began to be understood in the 1800s.

However, recall that cellulose linkages are β-1.4-glucosidic bonds. These bonds are much more difficult to break, and due to cellulose crystallinity, breaking cellulose down into glucose is even more difficult. It was only during WWII that enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose was discovered. Instead of enzymes called amylases, the enzymes that degrade cellulose are called cellulases.

Cellulases are not a single enzyme. There are two main approaches to biological cellulose depolymerization: complexed and non-complexed systems. Each cellulase enzyme is composed of three main parts, and there are multiple synergies between enzymes.

5.3a The Reaction of Cellulose: Cellulolysis

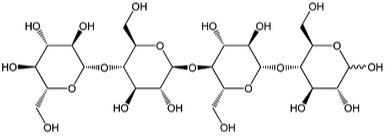

5.3a The Reaction of Cellulose: Cellulolysis djn12Cellulolysis is essentially the hydrolysis of cellulose. In low and high pH conditions, hydrolysis is a reaction that takes place with water, with the acid or base providing H+ or OH- to precipitate the reaction. Hydrolysis will break the β-1,4-glucosidic bonds, with water and enzymes to catalyze the reaction. Before discussing the reaction in more detail, let’s look at the types of intermediate units that are made from cellulose. The main monomer that composes cellulose is glucose. When two glucose molecules are connected, it is known as cellobiose – one example of a cellobiose is maltose. When three glucose units are connected, it is called cellotriose – one example is β -D pyranose form. And four glucose units connected together are called cellotetraose. Each of these is shown below.

We’ve seen the types of intermediates, so now let’s see the reaction types that are catalyzed by cellulose enzymes. The steps are shown below.

- Breaking of the noncovalent interactions present in the structure of the cellulose, breaking down the crystallinity in the cellulose to an amorphous strand. These types of enzymes are called endocellulases.

- The next step is hydrolysis of the chain ends to break the polymer into smaller sugars. These types of enzymes are called exocellulases, and the products are typically cellobiose and cellotetraose.

- Finally, the disaccharides and tetrasaccharides (cellobiose and cellotetraose) are hydrolyzed to form glucose, which are known as β-glucosidases.

Okay, now we have an idea of how the reaction proceeds. However, there are two types of cellulase systems: noncomplexed and complexed. A noncomplexed cellulase system is the aerobic degradation of cellulose (in oxygen). It is a mixture of extracellular cooperative enzymes. A complexed cellulase system is an anaerobic degradation (without oxygen) using a “cellulosome.” The enzyme is a multiprotein complex anchored on the surface of the bacterium by non-catalytic proteins that serve to function like individual noncomplexed cellulases but are in one unit. The figure below shows how the two different systems act. However, before going into more detail, we are now going to discuss what the enzymes themselves are composed of. The reading by Lynd provides some explanation of how the noncomplexed versus the complexed systems work.

This image is a comparative illustration of two distinct mechanisms for cellulose degradation, presented in two labeled panels: A and B. Panel A focuses on the free enzyme system, where individual enzymes act independently to break down cellulose. At the top, the structure of cellulose is shown, highlighting both crystalline and amorphous regions. Below, various enzymes—including endoglucanase, exoglucanase (CBHI and CBHII), and β-glucosidase—are illustrated interacting with the cellulose fibers. These enzymes work in concert to hydrolyze the cellulose into simpler sugars such as glucose, cellobiose, and cello-oligosaccharides.

Panel B illustrates the cellulosome-mediated degradation pathway, a more structured and synergistic approach. At the top, bacterial cell walls are shown with scaffoldin proteins anchored to them. These scaffoldins contain cohesin moieties that specifically bind to dockerin-containing enzymes like endoglucanase (CelF/CelS) and exoglucanase (CelE). The bottom part of this panel shows these enzymes forming a multi-enzyme complex, working together to efficiently degrade both crystalline and amorphous cellulose into simpler sugars.

A legend at the bottom of the image provides symbolic representations for the various components involved, including different enzymes, sugar products, and structural modules like carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs) and phosphorylases. Overall, the image serves as a detailed visual comparison of the free enzyme system versus the cellulosome system in the biochemical breakdown of cellulose.

5.3b Composition of Enzymes

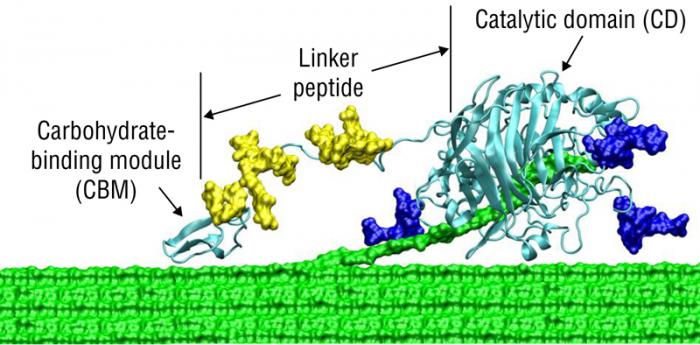

5.3b Composition of Enzymes djn12The first place to start is to describe the structure of a cellulase using typical terms in biochemistry. A modular cellobiohydrolase (CBH) has a few aspects in common; the common features include 1) a binder region of the protein, 2) a catalytic region of the protein, and 3) a linker region that connects the binder and catalytic regions. the first figure below shows a general diagram of the common features of a cellulase. The CBH acts on the terminal end of a crystalline cellulosic substrate, where the cellulose binding domain (CBD) is embedded in the cellulose chain, and the strand of cellulose is digested by the enzyme catalyst domain to produce cellobiose. This type of enzyme is typical of exocellulases. The second figure shows a more realistic model, where the linker is attached to the surface of the cellulose.

One of the main differences between glycosyl hydrolases (a type of cellulase) and the other enzymes is how the catalytic domain functions. There are three types: 1) pocket, 2) cleft, and 3) tunnel. Pocket or crater topology is optimal for the recognition of a saccharide non-reducing extremity and is encountered in monosaccharidases. Exopolysaccharidases are adapted to substrates having a large number of available chain ends, such as starch. On the other hand, these enzymes are not very efficient for fibrous substrates such as cellulose, which has almost no free chain ends. Cleft or groove cellulase catalytic domains are “open” structures, which allow a random binding of several sugar units in polymeric substrates and are commonly found in endo-acting polysaccharidases such as endocellulases. Tunnel topology arises from the previous one when the protein evolves long loops that cover part of the cleft. Found so far only in CBH, the resulting tunnel enables a polysaccharide chain to be threaded through it. The red portions on each catalytic domain are supposed to be the carbohydrates being processed, although it is difficult to see in this picture.

This image presents a detailed schematic of the molecular interaction between crystalline cellulose and a cellulolytic enzyme, emphasizing the structural and functional components involved in cellulose degradation. On the left side, the crystalline cellulose is depicted, with annotations highlighting the hydrogen bonds and Van der Waals interactions that contribute to its tightly packed, rigid structure. These interactions are crucial in maintaining the stability and resistance of cellulose to enzymatic attack.

At the interface between the cellulose and the enzyme, a glycosylation site is marked, indicating a point of biochemical interaction where the enzyme may be modified or anchored to enhance its activity or stability. The enzyme itself is divided into three distinct regions: the Cellulose Binder, which facilitates attachment to the cellulose surface; the Linker Region, which provides flexibility and spatial orientation; and the Catalytic Domain, where the actual hydrolysis of cellulose occurs.

On the right side of the image, cellobiose is shown as the primary product of this enzymatic reaction, representing a disaccharide unit released from the cellulose chain. This diagram effectively illustrates the complex interplay between enzyme structure and cellulose architecture, offering insight into the biochemical mechanisms underlying cellulose degradation.

Catalytic Domains of Glycosyl Hydrolases – A) pocket, B) cleft, and C) tunnel.

Catalytic Domains of Glycosyl Hydrolases:

Pocket-glucoamylase from A. awamori, Hydrolysis of amorphous polymers or dimers (e.g. starch and cellobiose)

Cleft - Endoglucanase (Cel6A) from T. fusca Hydrolysis of crystalline polymers (e.g. cellulose endoglucanases)

Tunnel - exoglucanase CHBII (Cel6A) from T. reesei, processive hydrolysis of crystalline polymers (e.g. exoglucanases)

The other main feature of these enzymes is the cellulose binding domain or module (CBD or CBM). Different CBDs target different sites on the surface of the cellulose; this part of the enzyme will recognize specific sites, help to bring the catalytic domain close to the cellulose and pull the strand of cellulose molecule out of the sheet so the glycosidic bond is accessible.

So now, let’s go back to noncomplexed versus complexed cellulase systems. The first figure below is another comparison of noncomplexed versus complexed cellulase systems, but this time, it focuses on the enzymes. Notice in Figure A below, the little PacMan look-alike figures for enzymes. The enzymes are separate but work in concert to break down the cellulose strands into cellobiose and glucose. Recall that this process is aerobic (in oxygen).

Now look at Figure B and the complexed system. The enzymes are attached to subunits that are attached to the bacterium cell wall. The products are the same, but recall that this system is anaerobic (without oxygen), and these enzymes all work together to produce cellobiose and glucose.

Patthra Pason, Chakrit Tachaapaikoon, Khin Lay Kyu,

Kazuo Sakka, Akihiko Kosugi and Yutaka Mori (2013). Paenibacillus curdlanolyticus Strain B-6 Multienzyme Complex: A Novel System for Biomass Utilization, Biomass Now - Cultivation and Utilization, Dr. Miodrag Darko Matovic (Ed.), ISBN: 978-953-51-1106-1, InTech, DOI: 10.5772/51820.

So, what are those subunits that are essentially the connectors in the enzyme? The figure below shows a schematic of the types. The cellulosome is designed for the efficient degradation of cellulose. A scaffoldin subunit has at least one cohesin module that is connected to other types of functional modules. The CBM shown is a cellulose-binding module that helps the unit anchor to the cellulose. The cohesin modules are major building blocks within the scaffoldin; cohesins are responsible for organizing the cellulolytic subunits into the multi-enzyme complex. Dockerin modules anchor catalytic enzymes to the scaffoldin. The catalytic subunits contain dockerin modules; these serve to incorporate catalytic modules into the cellulosome complex. This is the architecture of the C. thermocellum cellulosome system. (Alber et al., CAZpedia, 2010). Within each cellulosome, there can be many different types of these building blocks. The last figure shows a block diagram of two different structures of T. neapolitana LamA and Caldicellulosiruptor strain Rt8B.4 ManA in a block diagram form. Due to the level of this class, we will not be going into any greater depth about these enzymes.

This image presents a structured table summarizing information about specific enzymes, their corresponding recombinant peptides, modular structures or primer binding positions, and the organisms from which they are derived. The table is divided into two main enzyme categories: LamA and ManA.

For the LamA enzyme, two recombinant peptides are listed: LamAm1 and LamAm3. These peptides are associated with modular structures or primer binding positions labeled as TNEALAMF (M1) TNEALAMR for LamAm1 and TNEALAMF3 (M3) TNEALAMR3 for LamAm3. The source organism for LamA is Thermotoga neapolitana, a thermophilic bacterium known for its ability to degrade complex carbohydrates at high temperatures.

For the ManA enzyme, three recombinant peptides are identified: ManAm12, ManAm1, and ManAm2. Their corresponding primer binding positions are RTMANAF (M1) RTMANAR1 for ManAm1, and RTMANAF2 (M2) RTMANAR2 for ManAm2. The organism of origin for ManA is Caldicellulosiruptor strain Rt8B.4, another thermophilic microorganism recognized for its cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic capabilities.

5.3c Hemicellulases and Lignin-degrading Enzymes

5.3c Hemicellulases and Lignin-degrading Enzymes djn12Hemicellulases work on the hemicellulose polymer backbone and are similar to endoglucanases. Because of the side chain, “accessory enzymes” are included for side-chain activities. An example of hemicellulase activity on arabinoxylan and the places where bonds are broken by enzymes are shown (blue) in the first figure below. The second figure shows another example of how hemicellulose breaks down hemicellulose, a complex mixture of enzymes, to degrade hemicellulose. The example depicted is cross-linked glucurono arabinoxylan.

The complex composition and structure of hemicellulose require multiple enzymes to break down the polymer into sugar monomers—primarily xylose, but other pentose and hexose sugars also are present in hemicelluloses. A variety of debranching enzymes (red) act on diverse side chains hanging off the xylan backbone (blue). These debranching enzymes include arabinofuranosidase, feruloyl esterase, acetylxylan esterase, and alpha-glucuronidase [The table below shows enzyme families for degrading the hemicellulose]...As the side chains are released, the xylan backbone is exposed and made more accessible to cleavage by xylanase. Beta-xylosidase cleaves xylobiose into two xylose monomers; this enzyme also can release xylose from the end of the xylan backbone or a xylo-oligosaccharide. (U.S. DOE, 2006)

| Enzyme | Enzyme Families |

|---|---|

| Endoxylanase | GH5, 8, 10, 11, 43 |

| Beta-xylosidase | GH3, 39, 43, 52, 54 |

| Alpha-L-arabinofuranosidase | GH3, 43, 51, 54, 62 |

| Alpha-glucurondiase | GH4, 67 |

| Alpha-galatosidase | GH4, 36 |

| Acetylxylan esterase | CE1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

| Feruloyl esterase | CE1 |

Lignin-degrading enzymes are different from hemicellulases and cellulases. They are known, as a group, as oxidoreductases. Lignin degradation is an enzyme-mediated oxidation, involving the initial transfer of single electrons to the intact lignin (this would be a type of redox reaction or reduction-oxidation reaction). Electrons are transferred to other parts of the molecule in uncontrolled chain reactions, leading to the breakdown of the polymer. It is different from carbohydrate hydrolysis because it is an oxidation reaction, and it requires oxidizing power (e.g., hydrogen peroxide, H2O2) to break the lignin down. In general, it is a significantly slower reaction than the hydrolysis of carbohydrates.

Examples of lignin-degrading enzymes include lignin peroxidase (aka ligninase), manganese peroxidase, and laccase, which contain metal ions involved in electron transfer. Lignin peroxidase (previously known as ligninase) is an iron-containing enzyme, that accepts two electrons from hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and then passes them as single electrons to the lignin molecule. Manganese peroxidase acts similarly to lignin peroxidase but oxidizes manganese (from H2O2) as an intermediate in the transfer of electrons to lignin. Laccase is a phenol oxidase, which directly oxidizes the lignin molecule (contains copper). There are also several hydrogen-peroxide-generating enzymes (e.g., glucose oxidase), which generate H2O2 from glucose. (Microbial World, The University of Edinburgh).

If you are interested in learning about the mechanisms of these enzymes, then visit the Department of Chemistry, University of Maine. Several pages discuss how each of the different types of enzymes works mechanistically.

Lesson 6 will discuss the process of ethanol production after the use of cellulases on cellulose.