Lesson 2: Existing Fossil Fuel Technologies for Transportation

Lesson 2: Existing Fossil Fuel Technologies for Transportation mjg8Overview

In the previous lesson, we learned that alternative fuels are a viable replacement for fossil fuels. But to make them viable, the fuels must fit into the current fuel structure and needs. This week's lesson focuses on transportation fuels - we will learn some chemistry about fuels (a short chemistry tutorial is first), how these fuels are currently made, and how these fuels are utilized. This provides a basis for understanding how alternative fuels must be chemically modified, so we do not have to make significant changes in utilization.

Lesson Objectives

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- explain the chemistry of gasoline, diesel fuel, jet fuel, and fuel oil;

- describe the basics of how these fuels are made by converting from crude oil;

- discuss the utilization of these fuels in cars, trucks, aircraft, and various engine types;

- evaluate necessary fuel characteristics for various vehicle engines.

Lesson 2 Road Map

This lesson will take us one week to complete. Please refer to the Course Syllabus for specific time frames and assignment due dates.

Questions?

If there is anything in the lesson materials that you would like to comment on or don't quite understand, please post your thoughts and/or questions to our Throughout the Course Questions and Comments discussion forum. The discussion forum will be checked regularly. While you are there, feel free to post responses to your classmates if you are able to help. Regular office hours will be held to provide help for EGEE 439 students.

2.1 Chemistry Tutorial

2.1 Chemistry Tutorial ksc17The chemical compounds that are important for understanding most of the chemistry in this course are organic - that means that the compounds primarily contain carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms (also sulfur and nitrogen). They can also be called hydrocarbons. The basic structures that we will be discussing in this course are called: 1) alkane (aka aliphatic), 2) branched alkane, 3) cycloalkane, 4) alkenes (double-bonds), 5) aromatic, 6) hydroaromatic, and 7) alcohols. First, I will show the atoms and how they are connected using the element abbreviation and lines as bonds, and then I will show abbreviated structural representations.

| Name | Atoms and Bonds | Stick Representation |

|---|---|---|

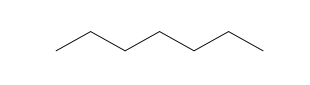

| Heptane (7 C atoms) |  |  |

| Name | Atoms and Bonds | Stick Representation |

|---|---|---|

| Isobutane (4 C atoms) |  |

|

| Isopentane (5 C atoms) |  |  |

| Name | Atoms and Bonds | Stick Representation |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclohexane (6 C atoms) |  |  |

| Name | Atoms and Bonds | Stick Representation |

|---|---|---|

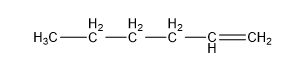

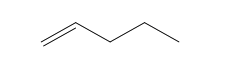

| Pentene (5 C atoms) |  |  |

| Name | Atoms and Bonds | Stick Representation |

|---|---|---|

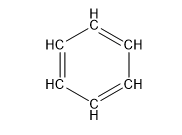

| Benzene (6 C atoms) |  |  |

| Name | Atoms and Bonds | Stick Representation |

|---|---|---|

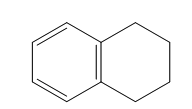

| 1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene, aka tetralin (10 C atoms) |  |  |

| Name | Atoms and Bonds | Stick Representation |

|---|---|---|

| Butanol (4 C atoms) |  |  |

| Ethanol (2 C atoms) |  |  |

The following table shows common hydrocarbons and their properties. It is important to know the properties of various hydrocarbons so that we can separate them and make chemical changes to them. This is a very brief overview - we will not yet be going into significant depth as to why the differences in chemicals affect the properties.

| Name | Number of C Atoms | Molecular Formula | bp (°C), 1 atm | mp (°C) | Density (g/mL) (@20°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | 1 | CH4 | -161.5 | -182 | -- |

| Ethane | 2 | C2H6 | -88.6 | -183 | -- |

| Propane | 3 | C3H8 | -42.1 | -188 | -- |

| Butane | 4 | C4H10 | -0.5 | -138 | -- |

| Pentane | 5 | C5H12 | 36.1 | -130 | 0.626 |

| Hexane | 6 | C6H14 | 68.7 | -95 | 0.659 |

| Heptane | 7 | C7H16 | 98.4 | -91 | 0.684 |

| Octane | 8 | C8H18 | 125.7 | -57 | 0.703 |

| Nonane | 9 | C9H20 | 150.8 | -54 | 0.718 |

| Decane | 10 | C10H22 | 174.1 | -30 | 0.730 |

| Tetradecane | 14 | C14H30 | 253.5 | 6 | 0.763 |

| Hexadecane | 16 | C16H34 | 287 | 18 | 0.770 |

| Heptadecane | 17 | C17H36 | 303 | 22 | 0.778 |

| Eicosane | 20 | C20H42 | 343 | 36.8 | 0.789 |

| Cyclohexane | 6 | C6H12 | 81 | 6.5 | 0.779 |

| Cyclopentane | 5 | C5H10 | 49 | -94 | 0.751 |

| Ethanol | 2 | C2H6O | 78 | -114 | 0.789 |

| Butanol | 4 | C4H10O | 118 | -90 | 0.810 |

| Pentene | 5 | C5H10 | 30 | -165 | 0.640 |

| Hexene | 6 | C6H12 | 63 | -140 | 0.673 |

| Benzene | 6 | C6H6 | 80.1 | 5.5 | 0.877 |

| Naphthalene | 10 | C10H8 | 218 | 80 | 1.140 |

| 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydronaphthalene | 10 | C10H12 | 207 | -35.8 | 0.970 |

2.2 Refining of Petroleum into Fuels

2.2 Refining of Petroleum into Fuels mjg8Much of the content in this particular section is based on information from Harold H. Schobert, Energy and Society: An Introduction, 2002, Taylor & Francis: New York, Chapters 19-24.

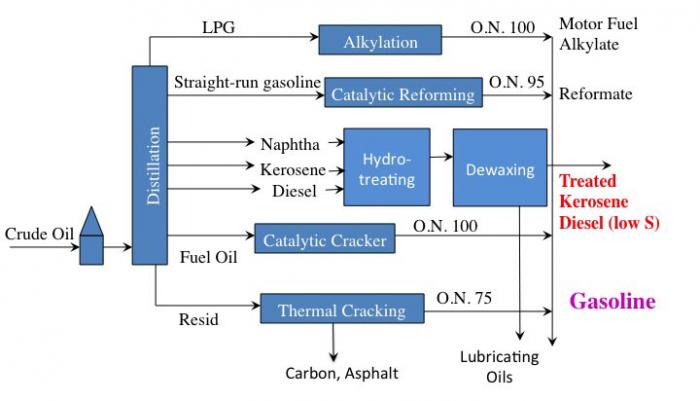

The following is a simplified flow diagram of a refinery. Since it looks relatively complicated, the diagram will be broken into pieces for better understanding.

Simple flow diagram of an oil refinery. Crude oil is the first process, and it breaks the products down into LPG, straight-run gasoline, naphtha/kerosene/diesel, fuel oil, and resid. LPG is used in the alkylation process to add carbons; straight-run gasoline is processed in a catalytic reformer to change to a branched-chain alkane; naphtha/kerosene/diesel is hydrotreated and dewaxed; fuel oil is catalytically cracked to make more gasoline, and resid is thermally cracked to make more gasoline.

Crude oil enters and goes to distillation. From distillation:

- LPG (gases) goes through alkylation to become O.N. 100 Motor Fuel Alkylate which can go on to become gasoline.

- Straight-run gasoline goes through catalytic reforming to become O.N. 95 Reformate which can go on to become gasoline.

- Naphtha, Kerosene, and Diesel all go through Hydrotreating and then dewaxing to become either treated Kerosene, Diesel (low sulfur), or lubricating oils.

- Fuel Oil goes through a catalytic cracker to become O/N 90-95 Gasoline.

- Resid goes through Thermal Cracking to become either Carbon, Asphalt, or O.N. 75 Gasoline.

Distillation

We will start with the first step in all refineries: distillation. Essentially, distillation is a process that heats crude oil and separates it into fractions. It is the most important process of a refinery. Crude oil is heated, vaporized, fed into a column that has plates in it, and the materials are separated based on the boiling point. It indicates that as the liquids are separated, the top-end materials are gases and lighter liquids, but as you go down the column, the products have a higher boiling point, the molecular size gets bigger, the flow of the materials gets thicker (i.e., increasing viscosity), and the sulfur (S) content typically stays with the heavier materials. Notice we are not using the chemical names, but the common mixture of chemicals. Gasoline represents the carbon range of ~ C5-C8, naphtha/kerosene (aka jet fuel) C8-C12, diesel C10-C15, etc. As we discuss the refinery, we will also discuss the important properties of each fuel.

The most important product in the refinery is gasoline. Consumer demand requires that 45-50 barrels per 100 barrels of crude oil processed are gasoline. The issues for consumers are, then: 1) quality suitability of gasoline and 2) quantity suitability. The engine that was developed to use gasoline is known as the Otto engine. It contains a four-stroke piston (and engines typically have 4-8 pistons). The first stroke is the intake stroke - a valve opens, allows a certain amount of gasoline and air, and the piston moves down. The second stroke is the compression stroke - the piston moves up and valves close so that the gasoline and air that came in the piston during the first stroke are compressed. The third stroke happens because the spark plug ignites the gasoline/air mixture, pushing the piston down. The fourth stroke is the exhaust stroke, where the exhaust valve opens and the piston moves back up. There is a good animation in How Stuff Works (Brain, Marshall. 'How Car Engines Work' 05 April 2000. HowStuffWorks.com).

Trends for products of the initial distillation

The image is a diagram of a distillation column used in the fractional distillation of crude oil, a key process in petroleum refining. The column is vertically oriented and segmented into several horizontal layers, each representing a different fraction collected during the distillation process. These fractions are separated based on their boiling points and other physical properties.

From Top to Bottom, the Fractions Are:

- Gases – The lightest and most volatile components, collected at the top.

- Gasoline – A light fuel used primarily in internal combustion engines.

- Naphtha – A volatile, flammable liquid used as a feedstock in petrochemical production.

- Kerosene – A heavier fuel used in jet engines and heating.

- Diesel – A mid-weight fuel used in diesel engines.

- Heating Oils – Heavier oils used for industrial heating and power generation.

- Resid – The heaviest fraction, often used for asphalt or further processing.

Accompanying Annotations:

To the right of the column, a vertical arrow points downward, indicating a gradient of physical properties as one moves down the column:

- Boiling Point (B.P) increases

- Molecular Size increases

- Viscosity increases

- Sulfur Content (S content) usually increases

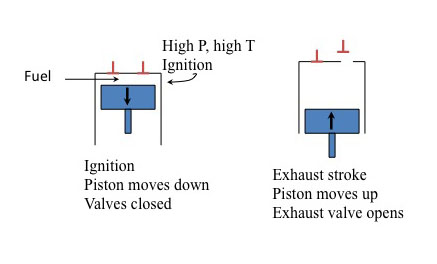

Four strokes of Otto gasoline engine

The diagram is divided into four vertical sections, each representing one of the four strokes in the engine cycle. Each section includes a labeled piston within a cylinder, directional arrows indicating piston movement, and annotations describing valve positions and actions.

Four strokes of Otto gasoline engine

- Intake stroke. The piston moves down. The intake valve opens.

- Compression stroke. The piston moves up. The valves close.

- Power stroke. The piston moves down. The valves closed.

- Exhaust stroke. The piston moves up. The exhaust valve opens.

You'll notice the x and the y on strokes 1 and 2. The ratio of x/y is known as the compression ratio (CR). This is a key design feature of an automobile engine. Typically, the higher the CR, the more powerful the engine is and the higher the top speed. The "action" is in the ignition or power stroke. The pressure in the cylinder is determined by 1) pressure at the moment of ignition (determined by CR) and 2) a further increase in pressure at the instant of ignition. At higher pressures with the CR, the more likely the pressure will cause autoignition (or spontaneous ignition), which can cause "knocking" in the engine - the higher the CR, the more likely the engine will knock. This is where fuel quality comes in.

For gasoline engines, the CR can be adjusted to the fuel rating to prevent knocking; this fuel quality is known as the "octane" number. Remember the straight-chain alkanes in the chemistry tutorial? The straight-chain alkanes are prone to knocking. The branched alkanes are not. The octane number is defined as 1) heptane - octane number equal to 0, and 2) 2,2,4-trimethylpentane - octane number equal to 100 (this is also known as "octane"). See the figure below for the chemical structures of heptane and octane for octane numbers. Modern car engines require an 87, 89, or 93-94 octane number. However, when processing crude oil, even high-quality crude oil, we can only produce from a distillation yield of 20% with an octane number of 50. This is why crude oil needs to be processed, to produce gasoline at 50% yield with an octane number of 87-94.

Other ways to improve the octane number:

- Add aromatics. Aromatics have an octane number (ON) greater than 100. They can be deliberately blended into gasoline to improve ON. However, many aromatic compounds are suspected carcinogens, so there are regulatory limits on the aromatic content in gasoline.

- Another approach to increasing ON is to add alcohol groups. Methanol and ethanol are typical alcohols that can be added to fuel. ON is ~110. They can be used as blends with racing cars (known as "alky").

But even with these compounds, distillation will not produce enough gasoline with a high enough ON. So other processes are needed.

"Cracking" Processes

Thermal cracking

One way to improve gasoline yield is to break the bigger molecules into smaller molecules - molecules that boil in the gasoline range. One way to do this is with "thermal cracking." Carbon Petroleum Dubbs was one of the inventors of a successful thermal cracking process. The process produces more gasoline, but the ON was still only ~70-73, so the quality was not adequate.

Catalytic cracking

Eugene Houdry developed another process; in the late 1930s, he discovered that thermal cracking performed in the presence of clay minerals would increase the reaction rate (i.e., make it faster) and produce molecules that had a higher ON, ~100. The clay does not become part of the gasoline - it just provides an active surface for cracking and changing the shape of molecules. The clay is known as a "catalyst," which is a substance that changes the course of a chemical reaction without being consumed. This process is called "catalytic cracking". The figure below shows the reactants and products for reducing the hexadecane molecule using both reactions. Catalytic cracking is the second most important process of a refinery, next to distillation. This process enables the production of ~45% gasoline with higher ON.

Below is the refining schematic with the additional processing added.

There are also tradeoffs when refineries make decisions as to the amount of each product they make. The quality of gasoline changes from summer to winter, as well as with gasoline demand. Prices that affect the quality of gasoline include 1) the price of crude oil, 2) the supply/demand of gasoline, 3) local, state, and federal taxes, and 4) the distribution of fuel (i.e., the cost of transporting fuel to various locations). Below is a schematic of how these contribute to the cost of gasoline and diesel.

Additional Processes

Alkylation

The alkylation process takes the small molecules produced during distillation and cracking and adds them to medium-sized molecules. They are typically added in a branched way in order to boost ON. An example of adding methane and ethane to butane is shown below.

Catalytic Reforming

A molecule may be of the correct number of carbon atoms but need a configuration that will either boost ON or make another product. The example below shows how reforming n-octane can produce 3,4-dimethyl hexane.

![]()

So, let's add these two new processes to our schematic in order to see how they fit into the refinery, and how this can change the ON of gasoline. The figure below shows the additions, as well as adding in the middle distillate fraction names. Typically, naphtha and kerosene, which can also be sold as these products, are the products that make up jet fuels. So, our next topic will cover how jet engines are different from gasoline engines and use different fuel.

Refining of crude oil into gasoline with additional processes of alkylation and catalytic reforming.

This is a simple flow diagram of a crude oil refinery.

Crude oil enters and goes to distillation. From distillation:

LPG (gases) goes through alkylation to become O.N. 100 Motor Fuel Alkylate which can go on to become gasoline

Straight-run gasoline goes through catalytic reforming to become O.N. 95 Reformate which can go on to become gasoline

Naphtha, Kerosene, and Diesel become jet fuels.

Fuel Oil goes through a catalytic cracker to become O.N 90-95 Gasoline

Resid goes through Thermal Cracking to O.N. 75 Gasoline.

2.3 Jet Engines

2.3 Jet Engines mjg8The first aircraft used engines similar to the Otto four-stroke cycle, reciprocating piston engines. The Wright Flyer was an aircraft with this type of engine. During WWII, powerful 16-cylinder, high-compression ratio reciprocating engines were developed. However, the military was interested in developing engines that would make airplanes go faster, higher, and farther - this was to reduce the length of flights and provide better international communication. In order to achieve high-speed flight, a dilemma ensued: 1) the atmosphere thins at high altitudes, offering less air resistance to a plane which could lead to higher speeds, but 2) in "thinner" air, it is more difficult to get combustion air into the conventional piston engine. The modern jet engine was developed as part of a term paper by Frank Whittle while at the British Royal Air Force College, covering the fundamental principles of jet propulsion aircraft.

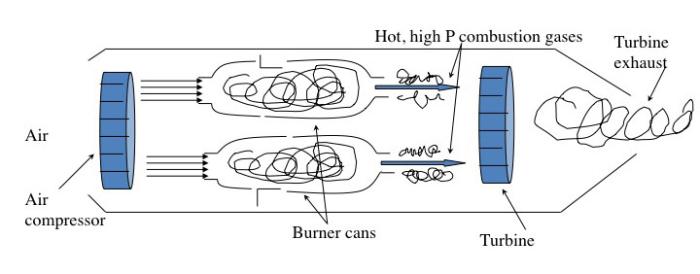

The jet engine begins with a "burner can," where jet fuel is injected and combusted in high-pressure air. The combustion produces a stream of high-temperature, high-pressure gases, as shown in the first figure below. If more power is required, two to four-burner cans can be included, and the high-temperature, high-pressure combustion gases operate a turbine (more about turbines for electricity generation in the lesson on electricity). The second figure depicts these additions. In the third figure, a containment vessel is put around the burner cans; the gases that exit the turbine pass through a nozzle. The gases exiting the nozzle provide thrust for the airplane. The fourth figure shows the completed engine - the high-pressure air comes from the air compressor, which is operated by the turbine.

There are variations on a simplistic jet engine: 1) the fan jet (turbofan), 2) the prop jet (turboprop), and 3) the turboshaft. The fan jet has a large fan in front of the engine to help provide air to the air compressor. It is a little slower than a turbojet but more fuel-efficient. This is the type favored for civilian transport aircraft. The prop jet uses the mechanical work of the turbine to operate a propeller. These types of engines are typically used for commuter aircraft. The turboshaft is a gas turbine engine that uses all of the output of the turbine to turn the blades, without jet exhaust. Helicopters, tanks, and hovercrafts use these types of engines. So, what is the fuel for jets?

Jet Fuel

Conventional jet fuel is composed primarily of straight-run kerosene (straight-chain carbons and accompanying hydrogen, bigger molecules than gasoline). However, there are some purification steps that are needed to ensure that the fuel behaves in jet engines.

The first step is the removal of sulfur. When sulfur is burned, it forms sulfur oxide compounds, such as sulfur dioxide (SO2) and sulfur trioxide (SO3). Because there are multiple sulfur oxide compounds, they are abbreviated into one chemical formula of SOx. These compounds, when combined with water, form acid rain (more on this in the next lesson on coal for electricity generation). Sulfur compounds are corrosive to fuel systems and have noxious odors. Sulfur is removed by reacting it with hydrogen and a metal catalyst; the processes are known as hydrogen desulfurization processes (HDS) and produce H2S (hydrogen sulfide), which is then reacted to solid sulfur.

Another problem that can occur with jet fuel is if it contains too much aromatic compound content. A small amount is actually necessary to lubricate gaskets and O-rings. However, aromatics are suspected carcinogens, and in combustion, aromatics are precursors to smoke and soot. Too much aromatic content can cause problems such as 1) poor aesthetics, 2) carcinogens, and 3) tracking of military aircraft. The way to remove aromatic compounds is the same as for removing sulfur; the aromatic compound is reacted with hydrogen and a metal catalyst to add hydrogen to the aromatic ring. The resulting compounds are heteroaromatics and cycloalkanes.

Another problem that can occur in the middle distillate fractions can occur if the fuel contains waxes. Waxes are higher molecular weight alkane hydrocarbons that can be dissolved in kerosene. At very cold temperatures at high altitudes, wax can either separate as a solid phase or cause the fuel to freeze and cause plugging in the fuel lines. This can also cause a problem called low-temperature viscosity. Viscosity is a measurement of the flow of a fluid; the thicker the fluid gets (and flow is reduced), the higher the viscosity. While the fuel isn't frozen, it is flowing slower and could cause problems for the engine. Again, the reason for the increase in viscosity is similar to having waxes in the kerosene; high viscosity is caused by bigger molecules within the fuel. The way to improve jet fuel properties is to remove the larger molecules. This is called dewaxing.

The last problem we will discuss has to do with nitrogen. Jet fuels do not typically contain nitrogen, but when combusting fuel using air (which contains primarily nitrogen), nitrogen oxide compounds can form, shown as a formula NOx. Because jet engines burn fuels at high temperatures, thermal NOx is a problem. NOx will contribute to acid rain. If there is any nitrogen in the fuel, it would be removed during the removal of sulfur.

A refinery will make ~10% of its product as jet fuel. The Air Force uses 10% of that fuel, so about 1% of refinery output is for military jet fuel. The figure below shows the additional processes just discussed in our schematic.

Primary processes that are typical in a petroleum refinery.

This is a simple flow diagram of a crude oil refinery.

Crude oil enters and goes to distillation. From distillation:

LPG (gases) goes through alkylation to become O.N. 100 Motor Fuel Alkylate which can go on to become gasoline

Straight-run gasoline goes through catalytic reforming to become O.N. 95 Reformate which can go on to become gasoline

Naphtha, Kerosene, and Diesel all go through Hydrotreating and then dewaxing to become either treated Kerosene, Diesel (low sulfur) or lubricating oils.

Fuel Oil goes through a catalytic cracker to become O/N 90-95 Gasoline

Resid goes through Thermal Cracking to become either Carbon, Asphalt, or O.N. 75 Gasoline.

2.4 Diesel Engines

2.4 Diesel Engines sxr133Rudolf Diesel first developed Diesel engines in the 19th century. He did so because he wanted to develop an engine that was more efficient than an Otto engine and that could use poorer quality fuel than gasoline. The Diesel engine also operates on a four-stroke cycle, but there are some important differences. Diesel engines have a high compression ratio (CR)- a small Diesel engine has a CR of 13:1, while a high-performance Otto engine has a CR of 10:1. Upon the compression stroke (stroke 2), there is a high increase in temperature and pressure. In the third stroke, fuel is injected and it ignites because of the high temperature and pressure of the compressed air. You can see an animation of this at How Stuff Works (Brain, Marshall. 'How Diesel Engines Work' 01 April 2000. HowStuffWorks.com). Diesel engines use fuel more efficiently; and under comparable conditions, a Diesel engine will always get better fuel efficiency than a gasoline Otto engine. Essentially, Diesel engines operate by knocking. The continuous knocking has two consequences: 1) a Diesel engine must be more sturdily built than a gasoline engine, so it is heavier and has a longer life - 300,000-350,000 miles before major engine service, and 2) fuel standards are "backward" from that of gasoline; we want fuel to knock.

Diesel Fuel

Diesel fuel has a much higher boiling range than gasoline. The molecules are larger than gasoline, and the octane scale cannot be used as a guide. The scale that is used for diesel fuel is called the cetane number. The compound, cetane, or hexadecane, C16H34, is the standard where the cetane number is 100. For the cetane number 0 (the other end of the scale), the chemical compound used is methylnaphthalene, an aromatic compound that doesn't knock. Most diesel fuels will have cetane numbers of 40-55, with the value in Europe on the higher end and the value in the US at the lower end of that range. In a refinery, diesel fuels are processed in the same fashion as jet fuels, using hydrogenation reactions to remove sulfur and nitrogen and reacting aromatics to hydro aromatics and cycloalkanes. Dewaxing also must be done to improve viscosity and low-temperature problems, particularly in colder climates. Therefore, the primary processes that are typical in a petroleum refinery apply to diesel fuel as well as jet fuel. Except in airplanes, diesel engines dominate internal combustion engine applications. They are standard for large trucks; dominate railways in North America and other countries; are common in buses; and are adapted in small cars and trucks, particularly in Europe.

Similar to gasoline, prices that affect the quality of diesel include 1) the price of crude oil, 2) the supply/demand of diesel, 3) local, state, and federal taxes, and 4) the distribution of fuel (i.e., the cost of transporting fuel to various locations). Above is a schematic of how these contribute to the cost of diesel.

2.5 Assignments Overview

2.5 Assignments Overview mjg8Quiz #2

Complete Quiz #2. It contains questions that pertain to the lesson material.

2.6 Summary and Final Tasks

2.6 Summary and Final Tasks sxr133Summary

This lesson was a very brief overview - there are entire classes based on this one lecture. In this lesson, we discussed the different transportation engines for vehicles, the fuels used for these vehicles, and how the fuels are produced from a refinery. Gasoline is the lighter fuel used in typical automobile engines, while diesel fuel is used in Diesel engines. Diesel engines get better fuel mileage than gasoline engines - gasoline is lighter than diesel. Here in the US, the primary fuel produced is gasoline (~45-50%).

Lesson Objectives Review

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- explain the chemistry of gasoline, diesel fuel, jet fuel, and fuel oil.

- describe the basics of how these fuels are made by converting from crude oil.

- discuss the utilization of these fuels in cars, trucks, aircraft, and various engine types.

- evaluate necessary fuel characteristics for various vehicle engines.

Questions?

If there is anything in the lesson materials that you would like to comment on, or don't quite understand, please post your thoughts and/or questions to our Throughout the Course Questions Comments discussion forum and/or set up an appointment during office hours. The discussion forum is checked regularly (Monday through Friday). While you are there, feel free to post responses to your classmates if you can help.