5.2 Biochemical Structural Aspects of Lignocellulosic Biomass

5.2 Biochemical Structural Aspects of Lignocellulosic Biomass ksc17For Review

To begin this part of Lesson 5, review the Biomass Carbohydrate Tutorial from the previous lesson. It will be important to remember all of the terminology for carbohydrates.

So, at this point, we’ve talked a bit about what lignocellulosic biomass is composed of, what various carbohydrates are chemically, and how to pretreat various biomass sources. Now, we will discuss the use of enzymes in biomass conversion, particularly in cellulose conversion. I’ll first introduce you to cellulases, and then we'll look at a model of enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose and enzymes for hemicellulose and lignin.

For cellulases, we’ll discuss what they are, provide a brief history, look at glycosyl hydrolases, and, finally, cellulases.

The processing of cellulose in lignocellulosic biomass requires several steps. We’ve discussed pretreatment, where cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose are separated. Hemicellulose is broken down into xylose and other sugars, which can then be fermented to ethanol. Lignin is separated out and can be further processed or burned depending on the best economic outcome. The first step of processing is then on the cellulose.

Preview of the process of producing ethanol from lignocellulosic biomass.

Producing Ethanol from lignocellulosic biomass:

Cellulose is pretreated so that hemicellulose is broken down to xylose, and other sugars are fermented to ethanol. Lignin is separated and burned: energy exceeds processing requirements.

Cellulose goes through enzymatic hydrolysis to produce glucose, which then goes through fermentation to produce 5% ethanol, which is distilled to produce 100% ethanol.

Pretreatment helps to decrystallize cellulose. However, it must be further processed to break it down into glucose, as it is glucose (a sugar) that can be fermented to make ethanol, and the liquid product must be further processed to make concentrated ethanol. So, we are focusing this lesson on the enzymatic hydrolysis of starch and cellulose.

5.2a Starch

5.2a Starch djn12We briefly addressed what starch is in Lesson 5. Now, we’ll go into a little more depth. In plants, starch has two components: amylose and amylopectin. Amylose is a straight-chain sugar polymer. Normal corn has 25% amylose, high amylose corn has 50-70% amylose and waxy corn (maize) have less than 2%. The rest of the starch is composed of amylopectin. Its structure is branched and is most commonly the major part of starch. Animals contain something similar to amylopectin, called glycogen. The glycogen resides in the liver and muscles as granules.

You can visit howstuffworks.com to see a schematic of what amylopectin looks like in a granule (see 'How Play-Doh Works') and then strands of the compound. The figure below shows some micrographs of starch as it begins to interact with water. When cooking with starch, you can make a gel from the polysaccharide. (A) This part of the figure shows polysaccharides (lines) packed into larger structures called starch granules; upon adding water, the starch granules swell and polysaccharides begin to diffuse out of the granules. Heating these hydrated starch granules helps polysaccharide molecules diffuse out of the granules and form a tangled network. (B) This is an electron micrograph of intact potato starch granules. (C) This is an electron micrograph of a cooked flaxseed gum network.

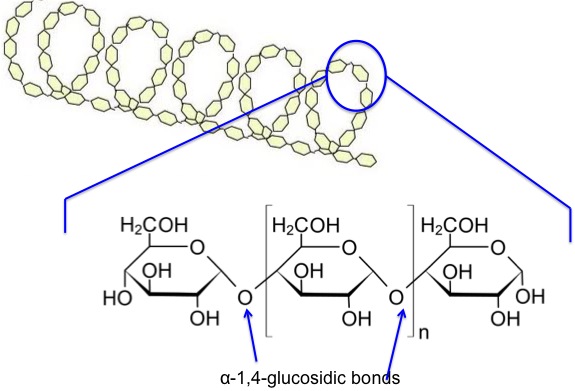

Now, let’s look at the starch components on a chemical structure basis. Amylose is a linear molecule with the α-1,4-glucosidic bond linkage. Upon viewing the molecule on a little larger scale, one can see it is helical. It becomes a colloidal dispersion in hot water. The average molecular weight of the molecule is 10,000-50,000 amu, and it averages 60-300 glucose units per molecule. Figure 6.5 depicts the chemical structure of amylose.

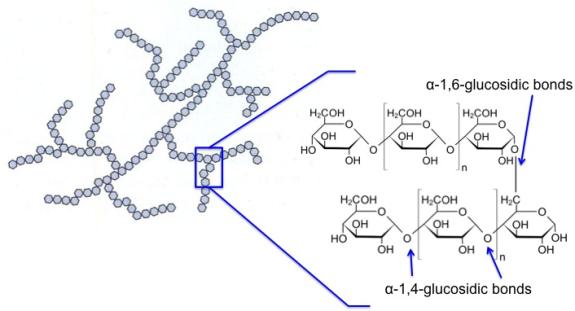

Amylopectin is branched, not linear, and is shown in the figure below. It has α-1,4-glycosidic bonds and α-1,6-glycosidic bonds. The α-1,6-glycosidic branches occur for about 24-30 glucose units. It is insoluble compared to amylose. The average molecular weight is 300,000 amu, and it averages 1800 glucose units per molecule. Amylopectin is about 10 times the size of amylose.

5.2b Cellulose

5.2b Cellulose djn12Cellulose is the most abundant polysaccharide, and it is also the most abundant biomass on earth. The linkages are slightly different from starch, called β-1,4-glycosidic linkages, as the bond is in a slightly different configuration or shape. This bond causes the strands of cellulose to be straighter (not helical). The hydrogen on one polymer strand can interact with the OH on another strand; this interaction is known as a hydrogen bond (H-bond), although it isn't an actual bond, just a strong interaction. This is what contributes to the crystallinity of the molecule. [Definition: the H-bond is not a bond like the C-H or C-O bonds are, i.e., they are not covalent bonds. However, there can be a strong interaction between hydrogen and oxygen, nitrogen, or other electronegative atoms. It is one of the reasons that water has a higher boiling point than expected.] The strands of cellulose form long fibers that are part of the plant structure. The average molecular weight is between 50,000 and 500,000, and the average number of glucose units is 300-2500.

5.2c Hemicellulose

5.2c Hemicellulose djn12As seen in previous lessons, lignocellulosic biomass contains another component, hemicellulose. Rather than being a typical polymer where units repeat over and over again, hemicellulose is a heteropolymer. It has a random, amorphous structure with little strength. It has multiple sugar units rather than the one glucose unit we’ve seen for starch and cellulose, and the average number of sugar units is 500-3000 (glucose units with the starch and cellulose). The monomer units include xylose, mannose, galactose, rhamnose, and arabinose units. The various polymers of hemicellulose include xylan, glucuronoxylan, arabinoxylan, glucomannan, and xyloglucan.

5.2d Lignin

5.2d Lignin djn12So, we’ve identified the chemical structures of starch, cellulose, and hemicellulose. Now we’re going to look at what lignin is, chemically.

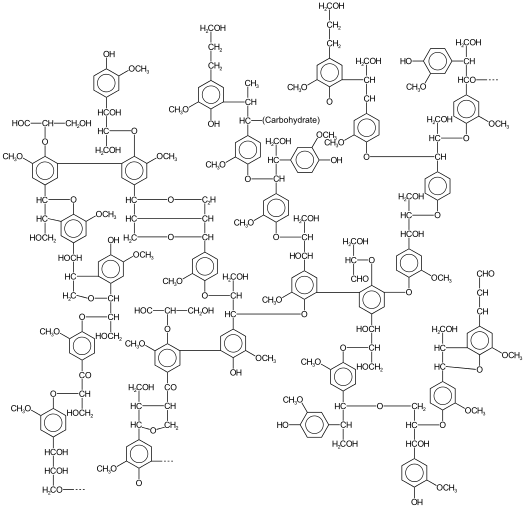

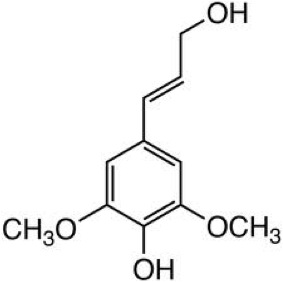

Vascular land plants make lignin to solve problems due to terrestrial lifestyles. Lignin helps to keep water from permeating the cell wall, which helps water conduction in the plant. Lignin adds support – it may help to “weld” cells together and provides stiffness for resistance against forces that cause bending, such as wind. Lignin also acts to prevent pathogens and is recalcitrant to degradation; it protects against fungal and bacterial pathogens (there is a discussion in Lesson 5 about recalcitrance). Lignin is comprised of crosslinked, branched aromatic monomers: p-coumaryl alcohol, coniferyl alcohol, and sinapyl alcohol; their structures are shown in the figures below and show how these building blocks fit into the lignin structure. p-Coumaryl alcohol is a minor component of grass and forage-type lignins. Coniferyl alcohol is the predominant lignin monomer found in softwoods (hence the name). Both coniferyl and sinapyl alcohols are the building blocks of hardwood lignin. The table below shows the differing amounts of lignin building blocks in the three types of lignocellulosic biomass sources.

| Lignin Sources | Grasses | Softwood | Hardwood |

|---|---|---|---|

| p-coumaryl alcohol | 10-25% | 0.5-3.5% | Trace |

| coniferyl alcohol | 25-50% | 90-95% | 25-50% |

| sinapyl alcohol | 25-50% | 0-1% | 50-75% |

Several different materials can be made from lignin, but most are not on a commercial scale. The table below shows the class of compounds that can be made from lignin and the types of products that come from that class of compounds. If an economic method can be developed for lignin depolymerization and chemical production, it would benefit the biorefining of lignocellulosic biomass.

| Class of Compound | Product Examples |

|---|---|

| Simple aromatics | Biphenyls, Benzene, Xylenes |

| Hydroxylated aromatics | Phenol, Catechol, Propylphenol, etc. |

| Aromatic Aldehydes | Vanillin, Syringaldehyde |

| Aromatic Acids and Diacids | Vanillic Acid |

| Aliphatic Acids | Polyesters |

| Alkanes | Cyclohexane |

There are also high molecular weight compounds. These include carbon fibers, thermoplastic polymers, fillers for polymers, polyelectrolytes, and resins, which can be made into wood adhesives and wood preservatives.