Lesson 5: General Ethanol Production

Lesson 5: General Ethanol Production sxr133Overview

This lesson will cover how ethanol is produced, from both starch and cellulose. In order to understand ethanol production, we will first learn about enzymes and their role in breaking down cellulose and starch into glucose so that fermentation can take place. The enzymes are the first stage, but there are several stages to producing ethanol. Most of you will not have any biochemistry background, so that’s where we’ll start. We will also cover a little about enzymes for hemicellulose and lignin degradation.

Before covering the technical aspects of the lesson, we will begin Lesson 6 with expectations for your final project.

Lesson Objectives

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- explain the requirements for the final report;

- recall the biochemistry of starch and lignocellulosic biomass, as well as go into greater depth on each of these components;

- discuss the basic biochemistry of enzymes;

- evaluate how the enzymes work and on certain biomass parts particular enzymes are used and products that are made.

Lesson 5 Road Map

This lesson will take us one week to complete. Please refer to the Course Syllabus for specific time frames and assignment due dates.

Questions?

If there is anything in the lesson materials that you would like to comment on or don't quite understand, please post your thoughts and/or questions to our Throughout the Course Questions and Comments discussion forum. The discussion forum will be checked regularly. While you are there, feel free to post responses to your classmates if you are able to help. Regular office hours will be held to provide help for EGEE 439 students.

5.1 Final Project (Biorefinery Project)

5.1 Final Project (Biorefinery Project) ksc17The final project will be due at the end of the semester. Toward the end of the semester, the homework will be less, so you’ll have ample opportunity to work on this. However, I am including the expectations now, so that you can begin to work on them.

Biomass Choice

You will be choosing a particular biomass to focus your report on. For the biomass you choose, you will need to do a literature review on the biomass and how and where it grows. Your requirements for location include 1) where it grows, 2) climate, 3) land area requirement, and 4) product markets near location. However, you are not to make a choice that already exists in the marketplace. This includes 1) sugarcane for ethanol production in Brazil and 2) corn for ethanol production in the Midwest of the USA. You need to put thought into what biomass you are interested in converting to fuels and chemicals, as well as where you want to locate your small facility. Most of all, choose biomass and location based on your particular interests, so as to make it interesting to you.

The literature review should consist of a list of at least ten resources that you have consulted from journals and websites of agencies such as IEA. If available, five of these sources should be from the last five years. Please use APA style for your references.

Location Choice and Method of Production

Once you have determined a biomass, choose a location based on previous information. Discuss your reasons for the choice of biomass, location, and desired products for production. Include a map of the area where you want to grow and market your product. You need to be aware of whether or not the biomass you choose can grow in the climate of the area you choose.

You will be choosing a method with which to convert your biomass into fuels. You are expected to include a schematic of the process units and a description of each process that will be necessary to do the biomass conversion; you should include what each process does and a little about the chemistry of each. Show the major chemical reactions that will take place in the process. The figures below show a process diagram and a chemical reaction, so you have an idea of what I expect.

Schematic of the sulfuric acid pretreatment process. This is a typical process schematic or diagram.

Market

The next section has to do with marketing your product. If you don’t have somewhere to sell your product, it will sit in a warehouse, maybe degrade (spoil is a more common term), and you won’t be making money on it. In the location you have chosen, is there a market for the product? If not, is there a location nearby where you can sell it? Discuss how you might market your products in the areas where you want to use biomass and sell products. How might you make the product you are selling appeal to the public? Due to the deregulation of electricity markets in various states, the prices of electricity will vary. Some companies charge more for renewable-based electricity, so they have to appeal to a particular market of people who are willing to spend more on renewable electricity.

Economics

We are going to assume that your process is going to be economic. However, any economic evidence that you can include that supports your process or indicates it would be a highly economical process will be beneficial to your paper. I would also like you to include any research and development that must occur for the process to become viable and economic (i.e., what is the current research on this process?).

Other Factors

Discuss other factors that could affect the outcome of implementing a bio-refining facility. What laws, such as environmental laws, might be in place? What is the political climate of the community you have chosen? What is the national political climate related to the biomass processing you have chosen? Are there any tax incentives that would encourage your process to be implemented or the product to be sold? An example would be something like this: all airlines in the US are expected to include a certain percentage of renewables in the jet fuel they use. So, would your process make jet fuel, and how would you market it to airlines? Include other factors that could “make or break” the facility.

Format

The report should be 8-12 pages in length. This includes figures and tables. It should be in 12-point font with 1” margins. You can use line spacing from 1-2. It is to be clearly communicated in English, with proper grammar, and as free from typographical errors as possible. You will lose points if your English writing is poor.

The following format should be followed:

- Cover Page – Title, Name, Course Info

- Introduction

- Body of Paper (see sections described above)

- Summary and Conclusions

- APA citation style for citations and references.

Grading Rubric:

- Outline: 10 points

- Rough Draft: 30 points

- Final Draft: 30 points

- Presentations (will be uploaded as videos): 30 points

- TOTAL: 100 points

Rubrics specific to each section of the final project are available in the submission dropboxes.

When submitting, please upload your final project to the Final Project Submission Dropbox. Save it as a PDF according to the following naming convention: userID_FinalProject (i.e., ceb7_FinalProject).

Attention:

Please remember that by submitting your paper in Canvas, you affirm that the work submitted is yours and yours alone and that it has been completed in compliance with University policies governing Academic Integrity, which, as a Penn State student, is your responsibility to understand and follow. Your projects will be reviewed closely for unattributed material and may be uploaded to the plagiarism detection service Turnitin.com to ensure originality. Academic dishonesty and lazy citation practices are not tolerated, and should you submit a paper that violates the Academic Integrity policies of the College and the University, be advised that the strictest penalties allowable by the University will be sought by your instructor. Please ask for help if you are concerned about proper citation.

Questions

If you have questions:

If there is anything in the lesson materials that you would like to comment on, or don't quite understand, please post your thoughts and/or questions to our Throughout the Course Questions Comments discussion forum and/or set up an appointment during office hours. The discussion forum is checked regularly (Monday through Friday). While you are there, feel free to post responses to your classmates if you can help.

5.2 Biochemical Structural Aspects of Lignocellulosic Biomass

5.2 Biochemical Structural Aspects of Lignocellulosic Biomass ksc17For Review

To begin this part of Lesson 5, review the Biomass Carbohydrate Tutorial from the previous lesson. It will be important to remember all of the terminology for carbohydrates.

So, at this point, we’ve talked a bit about what lignocellulosic biomass is composed of, what various carbohydrates are chemically, and how to pretreat various biomass sources. Now, we will discuss the use of enzymes in biomass conversion, particularly in cellulose conversion. I’ll first introduce you to cellulases, and then we'll look at a model of enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose and enzymes for hemicellulose and lignin.

For cellulases, we’ll discuss what they are, provide a brief history, look at glycosyl hydrolases, and, finally, cellulases.

The processing of cellulose in lignocellulosic biomass requires several steps. We’ve discussed pretreatment, where cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose are separated. Hemicellulose is broken down into xylose and other sugars, which can then be fermented to ethanol. Lignin is separated out and can be further processed or burned depending on the best economic outcome. The first step of processing is then on the cellulose.

Preview of the process of producing ethanol from lignocellulosic biomass.

Producing Ethanol from lignocellulosic biomass:

Cellulose is pretreated so that hemicellulose is broken down to xylose, and other sugars are fermented to ethanol. Lignin is separated and burned: energy exceeds processing requirements.

Cellulose goes through enzymatic hydrolysis to produce glucose, which then goes through fermentation to produce 5% ethanol, which is distilled to produce 100% ethanol.

Pretreatment helps to decrystallize cellulose. However, it must be further processed to break it down into glucose, as it is glucose (a sugar) that can be fermented to make ethanol, and the liquid product must be further processed to make concentrated ethanol. So, we are focusing this lesson on the enzymatic hydrolysis of starch and cellulose.

5.2a Starch

5.2a Starch djn12We briefly addressed what starch is in Lesson 5. Now, we’ll go into a little more depth. In plants, starch has two components: amylose and amylopectin. Amylose is a straight-chain sugar polymer. Normal corn has 25% amylose, high amylose corn has 50-70% amylose and waxy corn (maize) have less than 2%. The rest of the starch is composed of amylopectin. Its structure is branched and is most commonly the major part of starch. Animals contain something similar to amylopectin, called glycogen. The glycogen resides in the liver and muscles as granules.

You can visit howstuffworks.com to see a schematic of what amylopectin looks like in a granule (see 'How Play-Doh Works') and then strands of the compound. The figure below shows some micrographs of starch as it begins to interact with water. When cooking with starch, you can make a gel from the polysaccharide. (A) This part of the figure shows polysaccharides (lines) packed into larger structures called starch granules; upon adding water, the starch granules swell and polysaccharides begin to diffuse out of the granules. Heating these hydrated starch granules helps polysaccharide molecules diffuse out of the granules and form a tangled network. (B) This is an electron micrograph of intact potato starch granules. (C) This is an electron micrograph of a cooked flaxseed gum network.

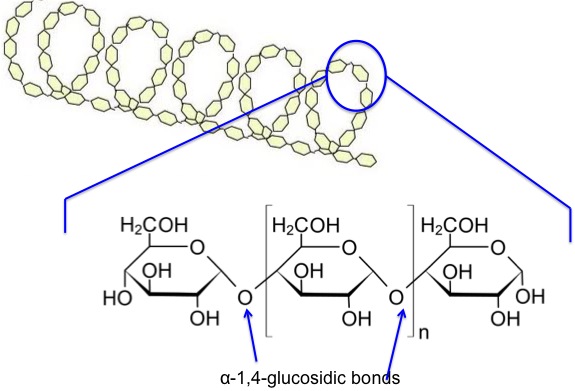

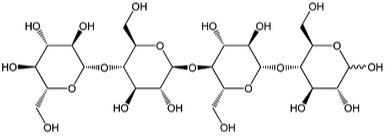

Now, let’s look at the starch components on a chemical structure basis. Amylose is a linear molecule with the α-1,4-glucosidic bond linkage. Upon viewing the molecule on a little larger scale, one can see it is helical. It becomes a colloidal dispersion in hot water. The average molecular weight of the molecule is 10,000-50,000 amu, and it averages 60-300 glucose units per molecule. Figure 6.5 depicts the chemical structure of amylose.

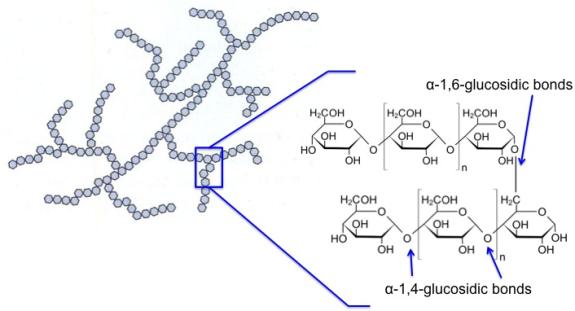

Amylopectin is branched, not linear, and is shown in the figure below. It has α-1,4-glycosidic bonds and α-1,6-glycosidic bonds. The α-1,6-glycosidic branches occur for about 24-30 glucose units. It is insoluble compared to amylose. The average molecular weight is 300,000 amu, and it averages 1800 glucose units per molecule. Amylopectin is about 10 times the size of amylose.

5.2b Cellulose

5.2b Cellulose djn12Cellulose is the most abundant polysaccharide, and it is also the most abundant biomass on earth. The linkages are slightly different from starch, called β-1,4-glycosidic linkages, as the bond is in a slightly different configuration or shape. This bond causes the strands of cellulose to be straighter (not helical). The hydrogen on one polymer strand can interact with the OH on another strand; this interaction is known as a hydrogen bond (H-bond), although it isn't an actual bond, just a strong interaction. This is what contributes to the crystallinity of the molecule. [Definition: the H-bond is not a bond like the C-H or C-O bonds are, i.e., they are not covalent bonds. However, there can be a strong interaction between hydrogen and oxygen, nitrogen, or other electronegative atoms. It is one of the reasons that water has a higher boiling point than expected.] The strands of cellulose form long fibers that are part of the plant structure. The average molecular weight is between 50,000 and 500,000, and the average number of glucose units is 300-2500.

5.2c Hemicellulose

5.2c Hemicellulose djn12As seen in previous lessons, lignocellulosic biomass contains another component, hemicellulose. Rather than being a typical polymer where units repeat over and over again, hemicellulose is a heteropolymer. It has a random, amorphous structure with little strength. It has multiple sugar units rather than the one glucose unit we’ve seen for starch and cellulose, and the average number of sugar units is 500-3000 (glucose units with the starch and cellulose). The monomer units include xylose, mannose, galactose, rhamnose, and arabinose units. The various polymers of hemicellulose include xylan, glucuronoxylan, arabinoxylan, glucomannan, and xyloglucan.

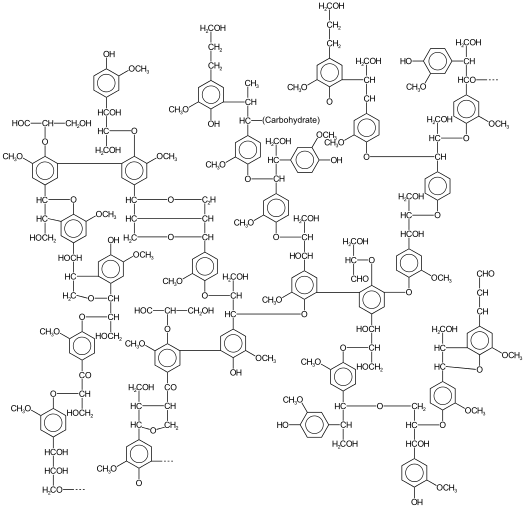

5.2d Lignin

5.2d Lignin djn12So, we’ve identified the chemical structures of starch, cellulose, and hemicellulose. Now we’re going to look at what lignin is, chemically.

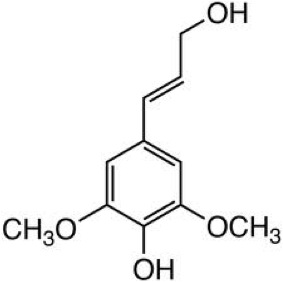

Vascular land plants make lignin to solve problems due to terrestrial lifestyles. Lignin helps to keep water from permeating the cell wall, which helps water conduction in the plant. Lignin adds support – it may help to “weld” cells together and provides stiffness for resistance against forces that cause bending, such as wind. Lignin also acts to prevent pathogens and is recalcitrant to degradation; it protects against fungal and bacterial pathogens (there is a discussion in Lesson 5 about recalcitrance). Lignin is comprised of crosslinked, branched aromatic monomers: p-coumaryl alcohol, coniferyl alcohol, and sinapyl alcohol; their structures are shown in the figures below and show how these building blocks fit into the lignin structure. p-Coumaryl alcohol is a minor component of grass and forage-type lignins. Coniferyl alcohol is the predominant lignin monomer found in softwoods (hence the name). Both coniferyl and sinapyl alcohols are the building blocks of hardwood lignin. The table below shows the differing amounts of lignin building blocks in the three types of lignocellulosic biomass sources.

| Lignin Sources | Grasses | Softwood | Hardwood |

|---|---|---|---|

| p-coumaryl alcohol | 10-25% | 0.5-3.5% | Trace |

| coniferyl alcohol | 25-50% | 90-95% | 25-50% |

| sinapyl alcohol | 25-50% | 0-1% | 50-75% |

Several different materials can be made from lignin, but most are not on a commercial scale. The table below shows the class of compounds that can be made from lignin and the types of products that come from that class of compounds. If an economic method can be developed for lignin depolymerization and chemical production, it would benefit the biorefining of lignocellulosic biomass.

| Class of Compound | Product Examples |

|---|---|

| Simple aromatics | Biphenyls, Benzene, Xylenes |

| Hydroxylated aromatics | Phenol, Catechol, Propylphenol, etc. |

| Aromatic Aldehydes | Vanillin, Syringaldehyde |

| Aromatic Acids and Diacids | Vanillic Acid |

| Aliphatic Acids | Polyesters |

| Alkanes | Cyclohexane |

There are also high molecular weight compounds. These include carbon fibers, thermoplastic polymers, fillers for polymers, polyelectrolytes, and resins, which can be made into wood adhesives and wood preservatives.

5.3 Enzymatic Biochemistry and Processing

5.3 Enzymatic Biochemistry and Processing djn12Starches are broken down by enzymes known as amylases; our saliva contains amylase, so this is how starches begin to be broken down in our body. Amylases have also been isolated and used to depolymerize starch for making alcohol, i.e., yeast for bread making and for alcohol manufacturing. Chemically, the amylase breaks the carbon-oxygen linkage on the chains (α-1,4-glucosidic bond and the α-1,6-glucosidic bond), which is known as hydrolysis. Once the glucose is formed, then fermentation can take place to break the glucose down into alcohols and CO2. The amylases were isolated and the hydrolysis of glucose began to be understood in the 1800s.

However, recall that cellulose linkages are β-1.4-glucosidic bonds. These bonds are much more difficult to break, and due to cellulose crystallinity, breaking cellulose down into glucose is even more difficult. It was only during WWII that enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose was discovered. Instead of enzymes called amylases, the enzymes that degrade cellulose are called cellulases.

Cellulases are not a single enzyme. There are two main approaches to biological cellulose depolymerization: complexed and non-complexed systems. Each cellulase enzyme is composed of three main parts, and there are multiple synergies between enzymes.

5.3a The Reaction of Cellulose: Cellulolysis

5.3a The Reaction of Cellulose: Cellulolysis djn12Cellulolysis is essentially the hydrolysis of cellulose. In low and high pH conditions, hydrolysis is a reaction that takes place with water, with the acid or base providing H+ or OH- to precipitate the reaction. Hydrolysis will break the β-1,4-glucosidic bonds, with water and enzymes to catalyze the reaction. Before discussing the reaction in more detail, let’s look at the types of intermediate units that are made from cellulose. The main monomer that composes cellulose is glucose. When two glucose molecules are connected, it is known as cellobiose – one example of a cellobiose is maltose. When three glucose units are connected, it is called cellotriose – one example is β -D pyranose form. And four glucose units connected together are called cellotetraose. Each of these is shown below.

We’ve seen the types of intermediates, so now let’s see the reaction types that are catalyzed by cellulose enzymes. The steps are shown below.

- Breaking of the noncovalent interactions present in the structure of the cellulose, breaking down the crystallinity in the cellulose to an amorphous strand. These types of enzymes are called endocellulases.

- The next step is hydrolysis of the chain ends to break the polymer into smaller sugars. These types of enzymes are called exocellulases, and the products are typically cellobiose and cellotetraose.

- Finally, the disaccharides and tetrasaccharides (cellobiose and cellotetraose) are hydrolyzed to form glucose, which are known as β-glucosidases.

Okay, now we have an idea of how the reaction proceeds. However, there are two types of cellulase systems: noncomplexed and complexed. A noncomplexed cellulase system is the aerobic degradation of cellulose (in oxygen). It is a mixture of extracellular cooperative enzymes. A complexed cellulase system is an anaerobic degradation (without oxygen) using a “cellulosome.” The enzyme is a multiprotein complex anchored on the surface of the bacterium by non-catalytic proteins that serve to function like individual noncomplexed cellulases but are in one unit. The figure below shows how the two different systems act. However, before going into more detail, we are now going to discuss what the enzymes themselves are composed of. The reading by Lynd provides some explanation of how the noncomplexed versus the complexed systems work.

This image is a comparative illustration of two distinct mechanisms for cellulose degradation, presented in two labeled panels: A and B. Panel A focuses on the free enzyme system, where individual enzymes act independently to break down cellulose. At the top, the structure of cellulose is shown, highlighting both crystalline and amorphous regions. Below, various enzymes—including endoglucanase, exoglucanase (CBHI and CBHII), and β-glucosidase—are illustrated interacting with the cellulose fibers. These enzymes work in concert to hydrolyze the cellulose into simpler sugars such as glucose, cellobiose, and cello-oligosaccharides.

Panel B illustrates the cellulosome-mediated degradation pathway, a more structured and synergistic approach. At the top, bacterial cell walls are shown with scaffoldin proteins anchored to them. These scaffoldins contain cohesin moieties that specifically bind to dockerin-containing enzymes like endoglucanase (CelF/CelS) and exoglucanase (CelE). The bottom part of this panel shows these enzymes forming a multi-enzyme complex, working together to efficiently degrade both crystalline and amorphous cellulose into simpler sugars.

A legend at the bottom of the image provides symbolic representations for the various components involved, including different enzymes, sugar products, and structural modules like carbohydrate-binding modules (CBMs) and phosphorylases. Overall, the image serves as a detailed visual comparison of the free enzyme system versus the cellulosome system in the biochemical breakdown of cellulose.

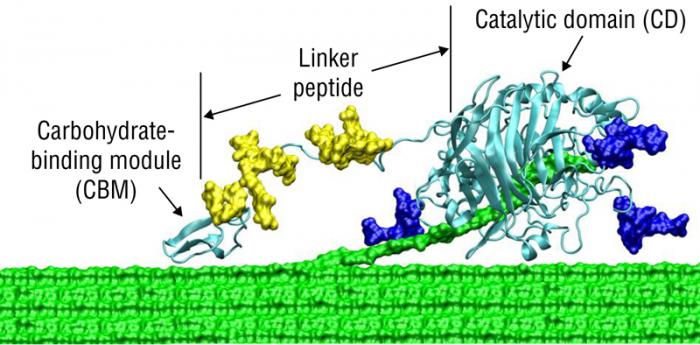

5.3b Composition of Enzymes

5.3b Composition of Enzymes djn12The first place to start is to describe the structure of a cellulase using typical terms in biochemistry. A modular cellobiohydrolase (CBH) has a few aspects in common; the common features include 1) a binder region of the protein, 2) a catalytic region of the protein, and 3) a linker region that connects the binder and catalytic regions. the first figure below shows a general diagram of the common features of a cellulase. The CBH acts on the terminal end of a crystalline cellulosic substrate, where the cellulose binding domain (CBD) is embedded in the cellulose chain, and the strand of cellulose is digested by the enzyme catalyst domain to produce cellobiose. This type of enzyme is typical of exocellulases. The second figure shows a more realistic model, where the linker is attached to the surface of the cellulose.

One of the main differences between glycosyl hydrolases (a type of cellulase) and the other enzymes is how the catalytic domain functions. There are three types: 1) pocket, 2) cleft, and 3) tunnel. Pocket or crater topology is optimal for the recognition of a saccharide non-reducing extremity and is encountered in monosaccharidases. Exopolysaccharidases are adapted to substrates having a large number of available chain ends, such as starch. On the other hand, these enzymes are not very efficient for fibrous substrates such as cellulose, which has almost no free chain ends. Cleft or groove cellulase catalytic domains are “open” structures, which allow a random binding of several sugar units in polymeric substrates and are commonly found in endo-acting polysaccharidases such as endocellulases. Tunnel topology arises from the previous one when the protein evolves long loops that cover part of the cleft. Found so far only in CBH, the resulting tunnel enables a polysaccharide chain to be threaded through it. The red portions on each catalytic domain are supposed to be the carbohydrates being processed, although it is difficult to see in this picture.

This image presents a detailed schematic of the molecular interaction between crystalline cellulose and a cellulolytic enzyme, emphasizing the structural and functional components involved in cellulose degradation. On the left side, the crystalline cellulose is depicted, with annotations highlighting the hydrogen bonds and Van der Waals interactions that contribute to its tightly packed, rigid structure. These interactions are crucial in maintaining the stability and resistance of cellulose to enzymatic attack.

At the interface between the cellulose and the enzyme, a glycosylation site is marked, indicating a point of biochemical interaction where the enzyme may be modified or anchored to enhance its activity or stability. The enzyme itself is divided into three distinct regions: the Cellulose Binder, which facilitates attachment to the cellulose surface; the Linker Region, which provides flexibility and spatial orientation; and the Catalytic Domain, where the actual hydrolysis of cellulose occurs.

On the right side of the image, cellobiose is shown as the primary product of this enzymatic reaction, representing a disaccharide unit released from the cellulose chain. This diagram effectively illustrates the complex interplay between enzyme structure and cellulose architecture, offering insight into the biochemical mechanisms underlying cellulose degradation.

Catalytic Domains of Glycosyl Hydrolases – A) pocket, B) cleft, and C) tunnel.

Catalytic Domains of Glycosyl Hydrolases:

Pocket-glucoamylase from A. awamori, Hydrolysis of amorphous polymers or dimers (e.g. starch and cellobiose)

Cleft - Endoglucanase (Cel6A) from T. fusca Hydrolysis of crystalline polymers (e.g. cellulose endoglucanases)

Tunnel - exoglucanase CHBII (Cel6A) from T. reesei, processive hydrolysis of crystalline polymers (e.g. exoglucanases)

The other main feature of these enzymes is the cellulose binding domain or module (CBD or CBM). Different CBDs target different sites on the surface of the cellulose; this part of the enzyme will recognize specific sites, help to bring the catalytic domain close to the cellulose and pull the strand of cellulose molecule out of the sheet so the glycosidic bond is accessible.

So now, let’s go back to noncomplexed versus complexed cellulase systems. The first figure below is another comparison of noncomplexed versus complexed cellulase systems, but this time, it focuses on the enzymes. Notice in Figure A below, the little PacMan look-alike figures for enzymes. The enzymes are separate but work in concert to break down the cellulose strands into cellobiose and glucose. Recall that this process is aerobic (in oxygen).

Now look at Figure B and the complexed system. The enzymes are attached to subunits that are attached to the bacterium cell wall. The products are the same, but recall that this system is anaerobic (without oxygen), and these enzymes all work together to produce cellobiose and glucose.

Patthra Pason, Chakrit Tachaapaikoon, Khin Lay Kyu,

Kazuo Sakka, Akihiko Kosugi and Yutaka Mori (2013). Paenibacillus curdlanolyticus Strain B-6 Multienzyme Complex: A Novel System for Biomass Utilization, Biomass Now - Cultivation and Utilization, Dr. Miodrag Darko Matovic (Ed.), ISBN: 978-953-51-1106-1, InTech, DOI: 10.5772/51820.

So, what are those subunits that are essentially the connectors in the enzyme? The figure below shows a schematic of the types. The cellulosome is designed for the efficient degradation of cellulose. A scaffoldin subunit has at least one cohesin module that is connected to other types of functional modules. The CBM shown is a cellulose-binding module that helps the unit anchor to the cellulose. The cohesin modules are major building blocks within the scaffoldin; cohesins are responsible for organizing the cellulolytic subunits into the multi-enzyme complex. Dockerin modules anchor catalytic enzymes to the scaffoldin. The catalytic subunits contain dockerin modules; these serve to incorporate catalytic modules into the cellulosome complex. This is the architecture of the C. thermocellum cellulosome system. (Alber et al., CAZpedia, 2010). Within each cellulosome, there can be many different types of these building blocks. The last figure shows a block diagram of two different structures of T. neapolitana LamA and Caldicellulosiruptor strain Rt8B.4 ManA in a block diagram form. Due to the level of this class, we will not be going into any greater depth about these enzymes.

This image presents a structured table summarizing information about specific enzymes, their corresponding recombinant peptides, modular structures or primer binding positions, and the organisms from which they are derived. The table is divided into two main enzyme categories: LamA and ManA.

For the LamA enzyme, two recombinant peptides are listed: LamAm1 and LamAm3. These peptides are associated with modular structures or primer binding positions labeled as TNEALAMF (M1) TNEALAMR for LamAm1 and TNEALAMF3 (M3) TNEALAMR3 for LamAm3. The source organism for LamA is Thermotoga neapolitana, a thermophilic bacterium known for its ability to degrade complex carbohydrates at high temperatures.

For the ManA enzyme, three recombinant peptides are identified: ManAm12, ManAm1, and ManAm2. Their corresponding primer binding positions are RTMANAF (M1) RTMANAR1 for ManAm1, and RTMANAF2 (M2) RTMANAR2 for ManAm2. The organism of origin for ManA is Caldicellulosiruptor strain Rt8B.4, another thermophilic microorganism recognized for its cellulolytic and hemicellulolytic capabilities.

5.3c Hemicellulases and Lignin-degrading Enzymes

5.3c Hemicellulases and Lignin-degrading Enzymes djn12Hemicellulases work on the hemicellulose polymer backbone and are similar to endoglucanases. Because of the side chain, “accessory enzymes” are included for side-chain activities. An example of hemicellulase activity on arabinoxylan and the places where bonds are broken by enzymes are shown (blue) in the first figure below. The second figure shows another example of how hemicellulose breaks down hemicellulose, a complex mixture of enzymes, to degrade hemicellulose. The example depicted is cross-linked glucurono arabinoxylan.

The complex composition and structure of hemicellulose require multiple enzymes to break down the polymer into sugar monomers—primarily xylose, but other pentose and hexose sugars also are present in hemicelluloses. A variety of debranching enzymes (red) act on diverse side chains hanging off the xylan backbone (blue). These debranching enzymes include arabinofuranosidase, feruloyl esterase, acetylxylan esterase, and alpha-glucuronidase [The table below shows enzyme families for degrading the hemicellulose]...As the side chains are released, the xylan backbone is exposed and made more accessible to cleavage by xylanase. Beta-xylosidase cleaves xylobiose into two xylose monomers; this enzyme also can release xylose from the end of the xylan backbone or a xylo-oligosaccharide. (U.S. DOE, 2006)

| Enzyme | Enzyme Families |

|---|---|

| Endoxylanase | GH5, 8, 10, 11, 43 |

| Beta-xylosidase | GH3, 39, 43, 52, 54 |

| Alpha-L-arabinofuranosidase | GH3, 43, 51, 54, 62 |

| Alpha-glucurondiase | GH4, 67 |

| Alpha-galatosidase | GH4, 36 |

| Acetylxylan esterase | CE1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 |

| Feruloyl esterase | CE1 |

Lignin-degrading enzymes are different from hemicellulases and cellulases. They are known, as a group, as oxidoreductases. Lignin degradation is an enzyme-mediated oxidation, involving the initial transfer of single electrons to the intact lignin (this would be a type of redox reaction or reduction-oxidation reaction). Electrons are transferred to other parts of the molecule in uncontrolled chain reactions, leading to the breakdown of the polymer. It is different from carbohydrate hydrolysis because it is an oxidation reaction, and it requires oxidizing power (e.g., hydrogen peroxide, H2O2) to break the lignin down. In general, it is a significantly slower reaction than the hydrolysis of carbohydrates.

Examples of lignin-degrading enzymes include lignin peroxidase (aka ligninase), manganese peroxidase, and laccase, which contain metal ions involved in electron transfer. Lignin peroxidase (previously known as ligninase) is an iron-containing enzyme, that accepts two electrons from hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and then passes them as single electrons to the lignin molecule. Manganese peroxidase acts similarly to lignin peroxidase but oxidizes manganese (from H2O2) as an intermediate in the transfer of electrons to lignin. Laccase is a phenol oxidase, which directly oxidizes the lignin molecule (contains copper). There are also several hydrogen-peroxide-generating enzymes (e.g., glucose oxidase), which generate H2O2 from glucose. (Microbial World, The University of Edinburgh).

If you are interested in learning about the mechanisms of these enzymes, then visit the Department of Chemistry, University of Maine. Several pages discuss how each of the different types of enzymes works mechanistically.

Lesson 6 will discuss the process of ethanol production after the use of cellulases on cellulose.

5.4 Assignments Overview

5.4 Assignments Overview djn12To Read

Please read Lynd, L. R., P. J. Weimer, W. H. Van Zyl, and I. S. Pretorius. "Microbial Cellulose Utilization: Fundamentals and Biotechnology." Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 66.3 (2002): 511-15. You can find a link to this reading in the Readings section of Lesson 5.

Quiz #3

You will be asked to complete Quiz #3. It contains questions that pertain to the lesson material.

5.5 Summary and Final Tasks

5.5 Summary and Final Tasks djn12Summary

In Lesson 5.1, we went over the requirements for the final project. In a future lesson, you will be expected to choose your biomass and outline your project.

Lesson 5.2 provided an overview of lignocellulosic biomass structure in greater depth than the previous lesson did. The greater depth is needed in order to understand how the enzymes work. You are expected to understand what lignocellulosic biomass is and how the components can break apart (i.e., what the fragments are chemically).

Lesson 5.3 discussed the basic composition of enzymes, how cellulosic enzymes (cellulases) work, and how hemicellulosic and lignitic enzymes work. The homework provided a background of what you need to know about enzymes.

Lesson Objectives

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- explain the requirements for the final report;

- recall the biochemistry of starch and lignocellulosic biomass, as well as go into greater depth on each of these components;

- discuss the basic biochemistry of enzymes;

- evaluate how the enzymes work, and on certain biomass parts, particular enzymes are used, and products that are made.

References

M. Bembenic and C.E.B. Clifford, “Subcritical water reactions of model compounds for a hardwood-derived Organosolv lignin with nitrogen, hydrogen, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide gases,” Energy Fuels, 27 (11), 6681-6694, 2013.

David Hodge, Wei Liao, Scott Pryor, Yebo Li, Enzymatic Conversion of Lignocellulosic Materials: BEEMS Module B2, sponsored by USDA Higher Education Challenger Program 2009-38411-19761.

Lee Lynd, P.J. Weimer, W.H. van Zyl, I.S. Pretorius, “Microbial cellulose utilization: Fundamentals and biotechnology,” Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 66 (3), 506-577, 2002.

Gideon Davies and Bernard Henrissat, “Structures and mechanisms of glycosyl hydrolases,” Structure, 3, 853-859, 1995.

Alber, O., Dassa, B., and Bayer, E., “Cellulosome” within the CAZpedia website, 2010, accessed June 5, 2014.

Summa, A., Gibbs, M.D., and Bergquist, P.L., “Identification of novel β-mannan- and β-glucan-binding modules: evidence for a superfamily of carbohydrate-binding modules,” Biochem. J., 356, 791-798, 2001.

U.S. DOE, Breaking the Biological Barriers to Cellulosic Ethanol: A Joint Research Agenda. DOE/SC-0095, U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science and Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, 2006.

Reminder - Complete all of the Lesson tasks!

You have reached the end of the Lesson. Double-check the Road Map on the Lesson Overview page to make sure you have completed the activity listed there before you begin the next Lesson.

Questions?

If there is anything in the lesson materials that you would like to comment on, or don't quite understand, please post your thoughts and/or questions to our Throughout the Course Questions & Comments discussion forum and/or set up an appointment during office hours. While you are there, feel free to post responses to your classmates if you can help.