What Are the Implications of Global Warming for Precipitation and Water Availability?

What Are the Implications of Global Warming for Precipitation and Water Availability? azs2So what does all this human-induced warming mean for the water cycle and water availability? Thinking back to module 2, you learned that warmer air can hold more water (i.e., warmer air has a higher saturation vapor pressure). Therefore it is reasonable to expect higher amounts of water vapor in the air. This is supported by observations that show a 3.5% increase in water vapor in the past 40 years as the climate has warmed about 0.5°C, with relative humidity remaining approximately constant.

Changes in precipitation are harder to measure (or predict) compared with changes in atmospheric water vapor content because of the immense temporal and spatial variability of precipitation. Nevertheless, patterns of precipitation change can readily be observed from historical records (Figure 2), with many areas seeing increases greater than 25 mm/year per decade (i.e., going from 300 mm/yr to 325 mm/yr over the course of a decade) and other places (particularly Africa and Southeast Asia) seeing decreases in precipitation at rates greater than 10 to 25 mm/year per decade. With increasing temperatures, it naturally follows that a greater proportion of precipitation would fall as rain, rather than snow, which has also been documented by the IPCC.

Learning Checkpoint

According to Figure 2, the two models (CRU and GPCC) indicate that, on average, precipitation throughout the conterminous US has ___________ from 1901 to 2019 (see left column of maps).

(a) increased

(b) decreased

(c) remained about the same

ANSWER: (a) increased

According to Figure 2, all three models indicate that, on average, precipitation throughout the conterminous US has ___________ from 1951 to 2019 (see right column of maps).

(a) increased in some areas and decreased in others

(b) decreased everywhere

(c) remained about the same

ANSWER: (a) increased in some areas and decreades in others. Note that the western US is seeing more dry conditions, and the eastern US is seeing more wet conditions.

Historical Precipitation Records and Climate Models

Historical Precipitation Records and Climate Models azs2What can the historical precipitation records and climate models tell us about the future?

But what can the historical precipitation records and climate models tell us about the future? Simulating future changes in precipitation patterns is one of the most difficult elements of climate modeling because precipitation and evaporation (there are feedbacks between the two so you have to model both) are driven by complex, non-linear processes. So climate models do not attempt to predict detailed representations of precipitation for any given location and climate models are generally not capable of predicting changes in precipitation intensity or frequency of extreme events, other than the likely sign (+ or -) of expected change. Nevertheless, all global climate models attempt to capture general trends in precipitation and considerable agreement exists among all the many competing models. In the broadest perspective, the IPCC makes the following important projections:

“Changes in the global water cycle in response to the warming over the 21st century will not be uniform. The contrast in precipitation between wet and dry regions and between wet and dry seasons will increase, although there may be regional exceptions.”

“Extreme precipitation events over most of the mid-latitude land masses and over wet tropical regions will very likely become more intense and more frequent by the end of this century, as global mean surface temperature increases (see Table SPM.1).”

“Globally, it is likely that the area encompassed by monsoon systems will increase over the 21st century. While monsoon winds are likely to weaken, monsoon precipitation is likely to intensify due to the increase in atmospheric moisture. Monsoon onset dates are likely to become earlier or not to change much. Monsoon retreat dates will likely be delayed, resulting in lengthening of the monsoon season in many regions.”

“There is high confidence that the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) will remain the dominant mode of inter-annual variability in the tropical Pacific, with global effects in the 21st century. Due to the increase in moisture availability, ENSO related precipitation variability on regional scales will likely intensify. Natural variations of the amplitude and spatial pattern of ENSO are large and thus confidence in any specific projected change in ENSO and related regional phenomena for the 21st century remains low.”

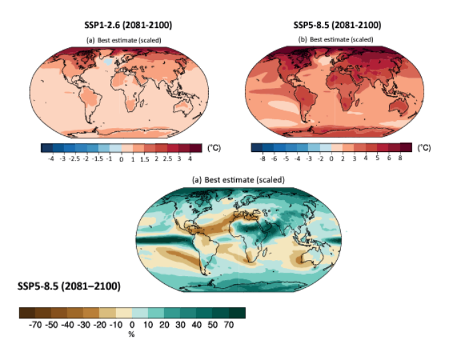

Figure 3 shows the average temperature and precipitation results of many different competing models for two different scenarios, comparing observations in 1995-2014 to the projected time period 2081-2100. The figures are aggregates of a number of competing climate models from CMIP6. The two scenarios, called ‘Shared Socio-economic Pathways’ (SSPs) 2.6 and 8.5 are the two end-members of greenhouse gas emissions, with SSP 2.6 assuming that greenhouse gas emissions peak in 2010-2020 time period and decrease aggressively thereafter and RCP 8.5 assuming that greenhouse gas emissions increase throughout the 21st century. Notice that the warming (top plots) is not uniform throughout the world. The higher latitudes, especially in the northern hemisphere are expected to heat up considerably more than the temperate or tropical latitudes. We often hear numbers of the global average increase in temperature (estimated 1-2°C or 2-3.5°F by 2050), but this average value does not represent what is expected to happen at high latitudes. A 3-4°C (5-7°F) increase in the arctic, as indicated by SSP 2.6, represents a dramatic transformation of this ecosystem. A 8-10°C (18-21°F) increase in the arctic, as indicated by SSP 8.5, would represent a complete transformation of this ecosystem. What do you think would be the potential benefits and damages caused by such a transformation?

Changes in precipitation are also not expected to be uniform. In general, increases or decreases in precipitation are expected to be more drastic in the high greenhouse gas emission scenario (SSP 8.5) with some areas receiving 30-40% changes relative to 1995-2014. What ecosystem, economic or social changes might you expect to see as a result of a 30-40% increase or decrease in precipitation in the arctic? In Spain? In South Africa? In Chile?

Figure 3. (IPCC chapter 4 figures 4.41 and 4.42) Maps of CMIP6 multi-model mean results for scenario SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5 for temperature and SSP5-8.5 for precipitation. Changes shown from 2081-2100 relative to 1995-2014 averages. IPCC.

Projected Changes

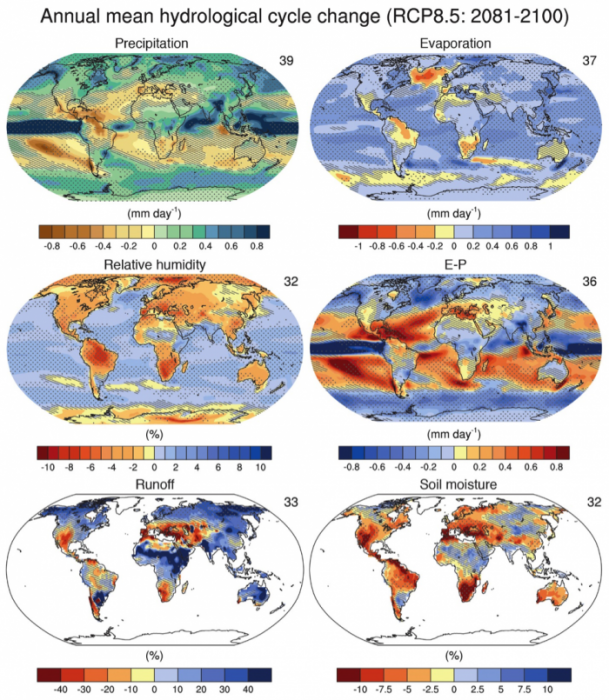

Projected Changes azs2Figure 4 illustrates projected changes in other parts of the hydrological cycle during the time period 2081-2100 relative to 1986-2005 according to the high greenhouse gas emissions scenario (RCP 8.5). Note that the number of competing climate models represented for each panel of the figure is indicated by a number in the top right (range: 32-39 different models are averaged for each prediction). Future projections of water runoff or soil moisture are dependent on precipitation, which, as discussed earlier, is itself subject to substantial uncertainties. Nevertheless, it is worth considering what the variety of competing climate models have to say. For example, note the general (if slight) decrease in relative humidity over most land masses and a slight increase in relative humidity over the oceans (middle panel, left column). The middle panel in the right column shows changes in the difference between evaporation and precipitation with blue colors indicating a relatively wetter future (more precipitation relative to evaporation) and red colors indicating a relatively drier future (more evaporation than precipitation). The bottom panel in the left column predicts changes in surface water runoff. Note the significant declines in runoff throughout the southwestern US and southern Europe/northern Africa and parts of South America. This same trend is amplified in predictions of soil moisture, which is a primary control on plant growth (bottom panel, right column).

Figure 4. (IPCC TFE.1, Figure 3) Annual mean changes in precipitation (P), evaporation (E), relative humidity, E – P, runoff and soil moisture for 2081–2100 relative to 1986–2005 under the Representative Concentration Pathway RCP8.5 (see Box TS.6). The number of Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 5 (CMIP5) models to calculate the multi-model mean is indicated in the upper right corner of each panel. Hatching indicates regions where the multi-model mean change is less than one standard deviation of internal variability. Stippling indicates regions where the multi-model mean change is greater than two standard deviations of internal variability and where 90% of models agree on the sign of change (see Box 12.1).