Groundwater Budgets

Groundwater Budgets azs2Now that you are an expert on how groundwater flows, we will apply that knowledge to the important problem of groundwater budgets. As groundwater flows through and exits an aquifer, for example at springs or at extraction wells, those losses of water may be balanced by recharge that percolates from the land surface. As you’ll investigate in the following section, and through a case study of the famous Ogallala aquifer in the American Midwest, understanding the budget of inflows and outflows to an aquifer is critical to evaluating the sustainability of groundwater use.

Fluxes (Inflows and Outflows) in Groundwater Systems

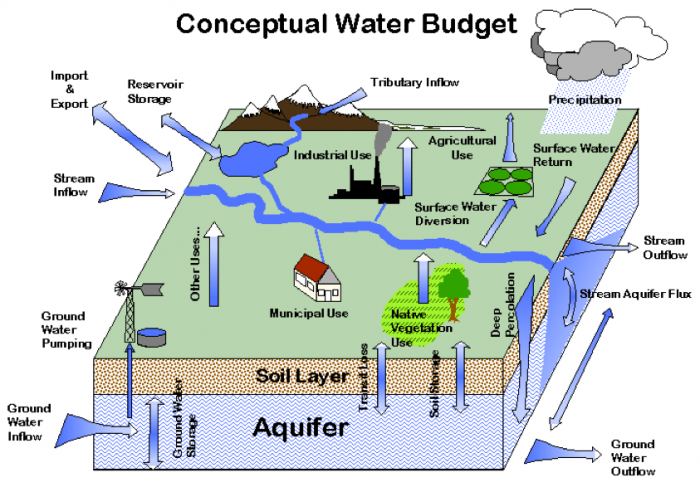

Fluxes (Inflows and Outflows) in Groundwater Systems azs2Fluxes (inflows and outflows) in Groundwater Systems: In order to define the water balance or water budget of an aquifer system, the individual processes that bring water into or out of the system must be quantified (Figure 37 on the next page).

Common inflows of water to a groundwater system include:

- Infiltration through the vadose zone that is not intercepted by evaporation, transpiration, or bound in the unsaturated zone, and thus becomes recharge. Infiltration may be distributed over large areas, or may be focused beneath surface water bodies or at geological features (e.g., sinkholes). Recharge may occur naturally or can be induced or enhanced by excavation and removal of low-permeability soils, and the construction of recharge pits, typically lined or filled with permeable sands (Figure 38 on the next page).

- Injection at wells, either for disposal of treated wastewater or as part of managed aquifer storage and recovery (ASR) programs. The latter is growing in popularity as one way to “bank” excess water in times of surplus, for example, wet seasons or wet years, and then tap the stored water when needed. Although energy-intensive because it requires pumping, ASR is not affected by evaporative losses whereas reservoirs are.

- Groundwater flow from areas outside of the region of interest – areas that are either up-gradient or above or below (i.e. flow across a confining layer).

Outflows from groundwater systems typically include:

- Evaporation or transpiration; this typically occurs in areas where the water table is shallow. Although direct evaporation of water from the water table is possible (in detail, this would occur by evaporation from the capillary fringe, and subsequent “wicking” of water upward from the water table), the upward flux (loss) of water from unconfined aquifers to the atmosphere is dominated by a family of plants known as phreatophytes, characterized by deep roots that extend to and below the water table.

- Water withdrawal by pumping from wells. As discussed in the previous section, pumping at wells induces radial flow toward the well. As the cone of depression grows, the well accesses water over a larger region of the aquifer. In some cases, as the cone of depression grows it may intercept water that would otherwise exit the aquifer via natural seeps or springs (e.g., Figure 37 on the next page), thus “redirecting” a flux that would have been an outflow somewhere else.

- Natural groundwater flow or discharge at springs or seeps, or to surface water bodies.

Surface Water-Groundwater Interaction

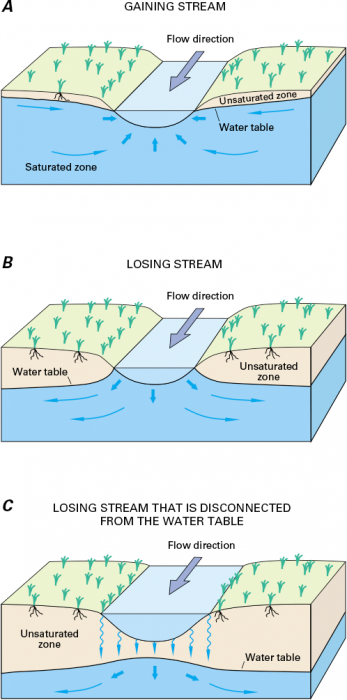

Surface Water-Groundwater Interaction azs2One specific class of inflow or outflow from groundwater systems results from surface water–groundwater interaction, water flows from aquifers into surface water bodies at seeps or springs, or infiltrates from rivers or lakes into aquifers (Figure 39; also note the dual-sided arrow between the aquifer and stream in Figure 37 indicating that the flux may be either to or from groundwater to surface water). If there is a net groundwater flux to surface water, the surface water body is said to be gaining (for example, a gaining stream is one that is fed by groundwater). As you may recall from Module 4, the component of streamflow derived from groundwater influx is termed baseflow. Alternatively, if the water table lies below the surface water body, the potential energy (hydraulic head) in the surface water body will be higher than in the groundwater system and water will percolate downward to the aquifer. In this configuration, the surface water body is said to be losing (i.e. a losing stream), because the stream or river discharge decreases downstream. While the land surface and stream channel generally remain at the same elevation, the water table commonly fluctuates over time (see Figures 32-33). As a result, it is common for streams to alternate between gaining to losing due to major recharge events, seasonality in precipitation and recharge, and variations in pumping rates.

Although water rights and policies are sometimes constructed with the implicit assumption that surface water and groundwater systems act independently, this is clearly not the case. A number of interesting situations arise from their interaction. As noted above in the Effects of Pumping Wells section, pumping at wells can reverse groundwater flow, and change a gaining stream to a losing one. In such a scenario, it isn’t always clear whether surface water rights are violated by groundwater pumping – even though groundwater extraction directly causes a reduction in surface water discharge, the water is withdrawn from the groundwater system, not the river. In large aquifer systems, the intercepted baseflow may impact users far downstream, across county and state borders. In other cases, also as noted earlier in this module, substantial or rapid influxes of surface water to groundwater systems, for example through fractures or sinkholes, can lead to groundwater contamination. If a direct connection between surface water and groundwater is demonstrated by the presence of microorganisms or increased water turbidity (cloudiness indicating suspended particles) in well water, additional treatment of groundwater is required before it is considered suitable for domestic or municipal use.

Water Budgets

Water Budgets azs2The balance of water inflows and outflows, or water budget, for a groundwater system, is described by a simple equation:

where I is the total of the inflows to the system, O the total outflows and ΔS is the change in storage. The water balance equation is no different than a bank statement: the difference between deposits (inflows) and withdrawals (outflows) is equal to the change in the account balance (storage). In the case of groundwater systems, changes in storage are manifested as changes in the potentiometric surface, either due to drop in the water table (in unconfined aquifers) or reduction in elastic storage as aquifer is depressurized (in confined aquifers).

In a steady state, or equilibrium condition, inflows and outflows are perfectly balanced (i.e. I = O in the budget equation above), and ΔS is zero. In other words, the potentiometric surface is steady. Often, groundwater systems are considered to be at steady state if inflows and outflows balance over a yearly or decadal timescale. This is because, in many aquifers, both recharge and extraction may be strongly seasonal. For example, recharge in many aquifers in the western US is mostly restricted to the winter months when precipitation is highest, and withdrawal rates are highest in the summer and early fall dry season. As a result, the potentiometric surface may fluctuate over the course of the year but is more-or-less constant over the long-term.

A variety of processes can lead to non-steady state conditions. Most notably in aquifers that are used heavily for irrigation, industry, or municipal supply, pumping may significantly exceed recharge, leading to net decreases in storage. In other cases, reduced recharge – for example due to urbanization and construction of impervious surfaces that do not allow infiltration, removal of leach fields upon installation of sewers (Figure 30), or long-term climate trends that drive changes in the amount or timing of precipitation – also results in negative changes in storage. Reductions in groundwater extraction, or periods of increased precipitation, will have the opposite effect and lead to increases in storage.

Overdraft

Overdraft azs2Groundwater overdraft is a specific condition in which extraction greatly exceeds the influxes of water (mainly recharge). This produces an unsustainable condition characterized by sustained declining water levels. Much like overdraft of a bank account, groundwater overdraft is not a desirable state of affairs. Not only is it unsustainable in terms of management of the groundwater resource, but it also leads to long-lasting damages (a lot like what happens to your credit rating if your bank account is overdrafted!).

Depressurization of the aquifer, if large enough, may cause irreversible collapse and compaction. This reduces both storage (porosity) .and hydraulic conductivity. It can also lead to land subsidence, especially in cases where the magnitude of overdraft is large and the aquifer units are thick and highly compressible, as is common for unconsolidated or uncemented sedimentary aquifers. One well-known example of groundwater overdraft is the Central Valley of California (Figure 41). Another is the Ogallala aquifer, a major groundwater system spanning across eight states in the American Midwest (Figure 43; see The High Plains Aquifer section). Substantial overdraft and subsidence also occur in widespread areas of the southeastern U.S., the Gulf Coast, and parts of Arizona and Las Vegas (Figure 44).