Seawater Desalination (SWRO)

Seawater Desalination (SWRO) jls164As you may remember from Module 1, the majority of Earth’s accessible water (i.e. not including a large amount of water trapped in minerals in the Earth’s interior!) is in the Oceans. In a sense, the Oceans would provide an unlimited supply of water, but of course, they are too salty to drink or use for most purposes. To use seawater for industrial, agricultural, or domestic/municipal supply, therefore, requires the separation of the water from the dissolved ions (mainly Na, Cl, Mg, SO4, Ca, and CO3). This can be accomplished in a variety of ways, but most commonly is done via either:

- Distillation, in which the water is forced to evaporate and then collected, leaving behind a concentrated brine, or

- Reverse osmosis, in which the water is forced through a semi-permeable membrane under pressure; the membrane physically excludes dissolved ions and other compounds, and only allows H2O molecules to pass (Figures 1 and 2).

Of these, reverse osmosis (or seawater reverse osmosis, SWRO) has emerged as the more efficient approach, especially when scaled to produce the millions of gallons per day or more needed to meet the demands of even modest population centers.

Of course, removing the salt from seawater requires energy – and money. For that reason, it has been a subject of intense research and engineering efforts, in order to reduce costs through increased scale, improved efficiency, pre-filtration, and improved materials (most importantly, advances in membrane materials that require less pressure to push the water through but still exclude dissolved ions). Early desalination plants were restricted to a relatively small scale, and mainly in desert areas (e.g., the Middle East), or to meet water quality requirements for the CO river treaty of 1944 (e.g., the Yuma desalination plant in Yuma, AZ, brought online in 1997). However, with improving efficiency, increasing demand, and perhaps spurred by drought, desalination is now emerging as one potential viable solution, at least in areas with access to the ocean, and the economic resources to construct and operate the plants.

SWRO and Energy Costs

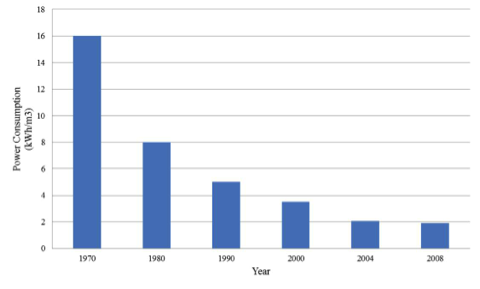

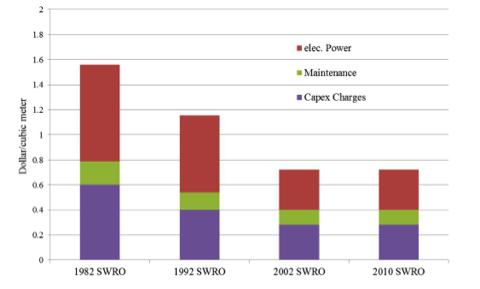

SWRO and Energy Costs azs2Technological advances, coupled with innovative approaches to reduce energy costs (i.e. by using solar, tidal, or ocean thermal energy) have helped to make SWRO a potential solution to water supply or hedge against climate change for large cities like Perth - rather than simply a novelty for wealthy countries. In the 1970s, SWRO costs hovered around $2.50/m3. Currently, costs for the most efficient plants are well below $1/m3, or between ~$1000-2000 per acre-foot (Figures 3 and 4). This is still more expensive than imported surface water or groundwater in most areas (these costs range from $400-1000/acre-foot, depending on location), but in the realm of viability for areas without those sources, or to augment limited supply. The total costs include everything from construction costs for the facility (amortized over its expected lifespan), land access, permitting for discharge and intakes, and operation & maintenance.

Despite its promise, it remains to be seen if SWRO will be a universal or large scale answer to water scarcity. In particular, key challenges include the (still relatively high) costs and associated energy demand; management of the environmental impact associated with intakes and disposal of the brine waste stream; delivery of SWRO water to regions away from the coast; and the up-scaling that would be necessary to meet demand for irrigation or industrial use.

| Year | Power Consumption (kWh/m3) |

|---|---|

| 1970 | 16 |

| 1980 | 8 |

| 1990 | 5 |

| 2000 | ~3 |

| 2004 | 2 |

| 2008 | ~2 |

| Year | Electric | Maintenance | Capex Charges | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1982 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 1.5 |

| 1992 | 0.6 | 0.15 | 0.4 | 1.15 |

| 2002 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.7 |

| 2010 | 0.35 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.75 |

Activate Your Learning

Current water rates (cost for the consumer) in Las Vegas are $1.16 per 1000 gallons. From the data shown in Figure 4, calculate the typical cost of SWRO per 1000 gallons for 2010. Do the same for 1982. How much higher are SWRO costs than current water rates in Las Vegas for the two cases (i.e. are they double the cost? Triple? Ten times?). (Hint: You’ll need to convert between m3 and gallons: one m3 is equivalent to 264 gallons.

1982: $1.55/m3 x 1m3/264 gallons = $0.0059/gallon x 1000 gallons = $5.90/1000gal. This is about 5 times the cost of typical water delivery in Las Vegas.

2010: $0.93/m3 x 1m3/264 gallons = $0.0035/gallon x 1000 gallons = $3.50/1000gal. This is about 3 times the cost of typical water delivery.