Module 3: Coastal Systems: Landscapes and Processes

Module 3: Coastal Systems: Landscapes and Processes sxr133Introduction

What types of sub environments exist across various coastal zones?

In Module 2, you were introduced to the variety of coastal landscapes that exist on a global basis and developed an understanding of how large-scale plate tectonics exert an influence on the characteristics of coastal zones. You also learned that an array of other factors, such as sediment supply, climate, and hydrographic regime, strongly affect how an individual coastal zone develops and evolves. In this module, the focus will be on developing an understanding of the many different types of specific coastal environments that can be present within a coastal zone, as well as the different types of processes that are active in these environments.

Goals and Objectives

Goals and Objectives sxr133- Students will build upon the material of Module 2 and be able to recognize that there are discrete, unique coastal systems such as rocky coasts, coral coasts, deltas, barrier islands, and marshlands within regional-scale coastal zones.

- Students will develop an understanding of what processes are operative within the range of coastal systems and how these processes shape the coastal systems.

- Students will appreciate that coastal systems evolve differently in response to fair-weather conditions or storm conditions.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, students should be able to:

- identify and describe the different types of coastal systems that exist;

- explain the morphological differences between these types of coastal systems.

Module 3 Roadmap

| Activity Type | Assignment |

|---|---|

| In addition to reading all of the required materials here on the course website, before you begin working through this module, please read the following required readings to make sure you are familiar with the content, so you can complete the assignments. Extra readings are clearly noted throughout the module and can be pursued as your time and interest allow. |

| To Do |

|

Questions?

If you have any questions, please use the Canvas email tool to contact the instructor.

Environments of Coastal Zones

Environments of Coastal Zones mjg8In what sort of tectonic setting would you expect rocky coasts most often? What is the role of different rock types in how erosion may take place along an uplifted, high wave energy rocky environment?

Rocky Coasts

Some estimates suggest that nearly 75% of the world’s shorelines are considered rocky coasts, meaning that the shoreline consists of erosionally resistant cohesive bedrock or sediment that has been recently cemented together to form a cohesive unit. Most often, rocky coasts are in areas of high wave energy and are erosional, with only localized areas where sediment might accumulate, such as small beaches between rocky headlands. They exist across a wide range of geologic settings, including very mountainous regions, areas that have been or are covered with glacial ice, or along volcanoes that are located in the open oceans. Although rocky coastlines may be present on passive, trailing tectonic margins, they are most frequently located along collisional tectonic margins.

Tectonics, Sediment Supply, and Morphologies Along Rocky Coasts

Tectonics, Sediment Supply, and Morphologies Along Rocky Coasts azs2Along active collisional margins, tectonic processes have uplifted and deformed rocks to create rugged landscapes with very little sediment input because of immature drainage basins along such geologically youthful landscapes. The presence of recently uplifted mountainous areas can also act as a barrier and prevent river systems from flowing, and thus carrying sediment, to the coast. Moreover, as you learned in Module 2, the relatively narrow and steep continental shelves that are characteristic of active tectonic margins do not help to dampen waves that move onshore from the open oceans. The result is that along active tectonic margins there is little delivery of sediment that could accumulate, and that sediment that does make it to the coast can be easily eroded and transported away by the high wave energy. Globally, there are many different types of morphologies along rocky coasts because of a wide range of rock types, styles of tectonic deformation, hydrographic regime, and styles of weathering.

Some of the most spectacular features of rocky coasts include sea arches and sea stacks, which are produced by the constant erosion of waves. A sea arch develops when a headland protruding into the ocean causes waves to refract around it. This refraction of waves concentrates their energy in specific locations along the headland, causing particularly rapid erosion if weakness such as faults and fractures are present in the rocks. In other cases, the waves may simply begin to erode into rock that is less resistant to erosion than the surrounding rock. Either way, the erosion leads to the development of small caves that may eventually meet below a promontory, leaving an arch above. The erosion continues and, for this reason, sea arches are very ephemeral coastal features. When they ultimately collapse, the remnants of the arch are called sea stacks.

For more information on sea arch formation and sea stacks, check out the following videos:

Video: West Wales - Sea Arches & Stacks (3:04)

West Wales - Sea Arches

To understand what's happening, we need to start at the southwestern corner of Wales, in Pembrokeshire. This is one of the most exposed parts of the Welsh coast because the prevailing winds are from the southwest. Waves driven across the Atlantic smash against the cliffs, continually wearing them away.

The harder pieces of coastline, like this headland, only erode quite slowly. But the softer bits, like that bay, get eroded much more quickly. And it's this difference, between hard and soft rocks, that leads to the repeating pattern of bays and headlands.

Although these cliffs are all made of the same material, carboniferous limestone, the rock isn't uniform throughout. It has weak layers, faults, and cracks running through it, all prime sites for erosion.

The erosion is due to several processes. There's hydraulic action, where the crashing waves compress water and air trapped in cracks, weakening and eventually loosening the rock. There's abrasive action, where material suspended in the water gets smashed up against the cliff face. And finally, there's chemical action, where the rock is dissolved by seawater and the rain. And just below where I'm standing is an absolutely stunning example of all these processes at work. This is the green bridge of Wales, a fabulous example of a sea arch.

If we go back 5 million years, the coast would have looked like this. First, the sea goes for the weak bands of rock, then it goes for the cracks in the harder rock, forming first arches and then stacks. This leaves the green bridge as we know it today. It's easy to guess what will happen in the future. Not all stacks are formed this way. Sometimes they just get left behind as the coastline around them erodes.

Those stacks will get worn down by the waves and the weather and become stumps like this one.

Video: How Caves, Arches, Stacks, and Stumps are Formed (1:58) (Video is not narrated.)

How Caves, Arches, Stacks, and Stumps are Formed

How Caves, Arches, Stacks, and Stumps are formed. By Katie Jamson.

First, headlands and bays are formed on a discordant coastline.

- HEADLAND

- BAY

- Bay sheltered by Headland (less erosion here)

- Hard Resistant Rock (little erosion) (e.g., limestone / chalk)

- Less Resistant Rock (lots of erosion) (e.g., Chalk / Sands and Clays)

- BAY

- Wave Direction (label pointing with arrows)

- DISCORDANT COASTLINE (Rocks outcrop at 90° to coastline)

- Bays and Headlands formed along this coastline due to differential erosion

- CONCORDANT COASTLINE (Rocks parallel to coastline)

- Wave Direction

This means the rock alternates between soft and hard rock. The rocks outcrop at a 90-degree angle to the coastline. This means the soft rock erodes quicker than the hard rock… forming Headlands and Bays. Headlands feel the full force of the waves. If there are any weaknesses in the form of cracks and faults, the sea will erode away the rock… This may eventually make caves mainly through hydraulic action. The cave is then widened and deepened by erosion to form an arch. As the roof of the arch is continually undercut, it eventually collapses, leaving an isolated stack caused by erosion and weathering. Again, these get eroded by the pounding waves and turn into stumps due to continual erosion. So, as you can see through the agents of erosion (hydraulic action, abrasion, attrition, and corrosion) along with weathering, landforms can change dramatically. Thank you for watching!

Learning Check Point

Learning Check Point mjg8Take a few minutes to think about what you just learned, and then answer the questions below.

Reef Coasts

Reef Coasts mjg8- What is the global distribution of coasts lined with coral reefs?

- Why are reefs globally distributed in this fashion?

- What are the different types of reef systems we see on a regional scale of kilometers or more?

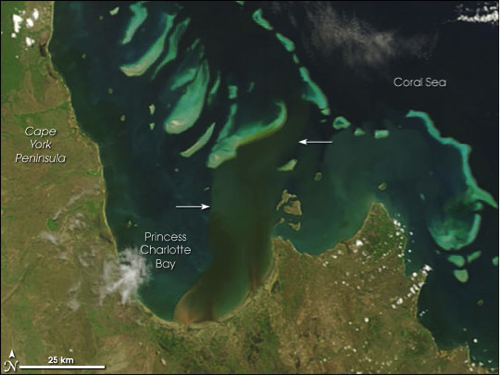

Historically, the exact definition of a reef has been a bit controversial, and different definitions would be provided if you were to ask a geologist or a biologist. For the purpose of this discussion, a reef can be considered any organic framework that is wave resistant and modifies the environment around it because of organic growth. Keep in mind that this definition offers no information about the type of organism creating the reef. Corals, shellfish such as oysters, and even some types of worms can create reefs, although the scale of reefs created by oysters and certain types of worms is much different than the scale of reefs that can be created by corals. The Great Barrier Reef of northeastern Australia extends for nearly, 2300 km and is the only organic structure that is visible from space, whereas oyster reefs are typically only several 10s of meters in length. Fundamentally, reefs rise above the substrate that they are sitting upon and thus modify or alter the speed and direction of currents and waves.

Global Distribution of Coral Reefs

Global Distribution of Coral Reefs azs2The vast majority of large reefs created by corals in shallow, sunlit waters (< 50 m water depth) are located within a tropical zone located between 30º N and 30º S latitude with a preferred temperature range of approximately 22º to 29º C. Corals also grow best in areas with little suspended sediment in the water, so large coral reefs systems are not common to locations where there is a large input of sediment to the coastal zone by river systems. Although there are cold, deep water types of coral present in the ocean basins, they do not create large nearshore reef structures that affect adjacent coasts.

In total, there are three main types of shallow water coral reef structures: 1) barrier reefs, 2) fringing reefs, and 3) coral atolls. These three types are differentiated on the basis of proximity to land, the overall scale of the reef structure, and the shape of the reef.

- Barrier reefs are typically large-scale, linear features that extend parallel to a shore, with a lagoon between the reef and the mainland.

- Fringing reefs are directly attached to the shore, with no well-developed lagoon between the reef structure and the mainland.

- Coral atolls are circular reefs that often start out as fringing reefs attached to a volcanic island. As the volcanic islands subside, the reef grows upward and a lagoon develops behind the reef and inside the submerging island. Eventually, the island can subside below the water level, and a ringlike coral reef structure remains.

Recommended Readings and Video: For more information on coral and coral reefs, check out these links:

- Coral Reef, Wikipedia

- Corals and Coral Reefs, Smithsonian Natural Museum of Natural History

- Atoll, Wikipedia

- Formation of coral islands, 38-second video

Learning Check Point

Learning Check Point mjg8Take a few minutes to think about what you just learned, then answer the questions below.

Nearshore, Beaches, and Dunes

Nearshore, Beaches, and Dunes sxr133How can beaches be zoned? What is the basis for this zonation: morphology or process? Why are some beaches steep and higher gradient than other beaches? What processes can drive sediment exchange between the nearshore, beaches, and dunes? How does the storm profile of a beach look compared to the fair weather profile for the same beach? If ample sediment is available, what can happen to a beach following a major loss of sediment? Can it recover? How?

For many of you, the concept of the nearshore, beach, and dunes probably conjures ideas such as swimming about in breaking waves, games of Frisbee on a sandy surface, or heavily vegetated mounds of sediment that have to be crossed in order to reach the beach. From a coastal geologist's morphological perspective, each of these has a unique definition, where the:

- nearshore is a broad classification defined as the region extending from the land water interface (shoreline) to a location just beyond where the waves are breaking,

- beach is defined as the zone of unconsolidated material that extends landward from the low water line to a place where there is a marked change in physiographic form or a line of permanent vegetation representing dunes,

- dunes are defined as topographically elevated ridges and or mounds that may be heavily vegetated, but are formed as sand is transported by wind and subsequently deposited.

Each of these environments is unique in form and composition and is characteristically molded by fundamentally different processes that act to modify each environment on a daily or longer timescale

Zonation by Tidal Elevations

Another convenient and slightly more simplistic way of dividing the nearshore through dune system is to recognize areas along such a transect as a function of where they lie relative to the tidal range for the area. In this sense, the nearshore through the dune system can be divided, on the basis of elevation relative to mean sea level, into subtidal, intertidal, and supratidal zones.

- Supratidal zone: is situated above the high tide elevation and only occasionally is flooded, most commonly during high spring tides and storms. It includes the uppermost part of the beach as well as the dunes, and so, the non-storm process acting to transport sediment in this area is wind (aeolian transport). In this context, this area is recognized as the backshore and dunes zone.

- Intertidal zone: is located between the normal low and high tide levels. This zone is therefore repeatedly inundated by water and exposed to air. This also represents the zone where waves are routinely interacting with the land, leading to daily transport of sediment. In the image above this area is recognized as the foreshore or beachface.

- Subtidal zone: consists of regularly submerged, relatively shallow water area seaward of the intertidal zone. Waves and tides are always acting to move sediment in this environment. In the image above, this area is recognized as the shoreface.

Nearshore

Nearshore azs2An examination of nearshore zones on a global basis reveals that they are characterized by a wide variety of morphologies, which are dependent upon the wave and tidal conditions as well as the size of sediment that is present. Overall, it is a zone in which there is generally the capability for significant sediment transport both perpendicular to the beach as well as alongshore because of longshore sediment transport by wave action. In some nearshore systems, there may be a variety of alongshore bars or ridges of sediment that can eventually migrate landward and attach to the beach and thereby contribute to the seaward extension of the beach.

Beach

Beach azs2The beach is located landward of the nearshore zonation and can consist of a wide range of sediment types including pebbles, gravel and even sediment particles that are as large as boulders. The composition of a beach can also be highly variable, and sediment on a beach can be anything from grains of the mineral quartz to fragments of calcium carbonate shell produced by shelled organisms. The size of the sediment as well as the composition of the sediment that is located on a beach is wholly a function of the character of the sediment that is available at that location. Because beaches are constantly being influenced by the impact of waves and by changes in the elevation of the water levels because of tides, they can be extremely dynamic environments, capable of undergoing drastic changes in morphology within a timescale that ranges between nearly instantaneous to seasonal or longer.

During high energy events, such as large storms or tropical cyclones, waves increase in size and therefore are more capable of eroding sediment from a beach and transporting it either farther offshore or along the shoreline to a new location in very short periods of time. During longer time periods, similar results can occur even during fair weather when low energy waves are affecting the beach. In general, however, most beaches undergo the most substantial erosion and loss of sediment during storm events and then experience a period of recovery to regain a cross-sectional profile that is in equilibrium with the wave and tidal conditions.

The slope of beaches can also be highly variable and is a function of the composition of the beach and the characteristics of the waves impacting the beach. Consider what happens as a wave breaks and the swash of the wave runs onto the beach and then returns. As a wave breaks onto a beach, it rushes up the slope of the beach and carries some sediment with it. The energy of the wave is expended due to friction with the surface and the pull of gravity downslope on the beach. As the water of the wave returns downslope, referred to as backwash, it still carries some sediment with it. However, if the beach is very coarse-grained, then the backwash can rapidly percolate into the subsurface and very little water remains to carry sediment back down the beach to the sea. In this case, any sediment carried up the beach by the breaking wave becomes stranded at the landward limit of the breaking wave, and no backwash is available to carry sediment back down to the base of the beach. Alternatively, if the beach is fine-grained and saturated with water, then the backwash cannot percolate into the subsurface, and as the water returns to the sea it carries relatively more sediment with it, leading to a gentle gradient. As a result, coarse-grained beaches with a significant amount of percolation have overall steeper gradients than fine-grained beaches under similar wave conditions.

Dunes

Dunes azs2Coastal dunes, often referred to as sand dunes, form where there is a readily available supply of sand-sized sediment and are located landward of the beach in the supratidal zone. The size of the sediment, duration, velocity, and direction of winds in the coastal zone, as well as the size and extent of vegetation, are fundamental properties that govern the size and shapes of dunes in coastal settings. The development and growth of dunes derive from the beach when the wind is blowing in an onshore direction. When the wind is blowing offshore, sediment in the dunes is transported back onto the beach or offshore into open water where it may later be carried back to the beach by waves.

Sand accumulates to create a dune system when the wind carrying the sand encounters an obstacle. Pieces of driftwood, trash, or piles of seaweed can all provide such an obstacle, causing the velocity of the wind to locally decrease, at which point the transport of the sand ceases and it is deposited. Most often, the obstacle that creates large continuous sand dunes is salt-water tolerant vegetation, either beach grasses or shrubs and trees depending upon the climate of the region. Vegetation, therefore, promotes the deposition of sand and acts to stabilize the dune system because of rooting.

During fair weather conditions, the base of the dunes is not affected by wave energy when a beach is in equilibrium with the prevailing conditions, because the waves dissipate on the beachface. During a storm, when water levels are elevated because of storm surge and large waves are being produced, a dune system may, however, be subjected to breaking waves that can cause erosion and the removal of significant volumes of sediment from the dunes. In extreme situations, dunes can be completely washed over by storm waves, completely flattened, and the sediment that was removed can be carried offshore, alongshore, or farther inland to create a wash over platform.

Overall, the presence of well-established dune systems act as barriers against storm waves and, thus, help to protect infrastructure that is located landward of the dune systems. For this reason, as well as the unique coastal ecosystems that they provide, dunes are very often protected environments. Fences around dunes and walkways above dune vegetation are common features in high traffic areas, and walking through dunes or riding motorized vehicles across them can be met with hefty fines and punishment because of the damage these activities can cause to the dune vegetation.

For more information on beach systems, check out these links:

- Information on different types of sand, Geology.com

- Explanation about the littoral system, Wikipedia

- Information about the nearshore and beaches, University of Puerto Rico, Department of Geology

- Review of beach processes along California, U.S., 4:48 minute video, Keith Meldahl, Professor of Geology and Oceanography, Mira Costa College

- Sand movement in dune systems, 5:32 minute video, Simon Haslett, Professor of Physical Geography, University of Wales

- Formation of Sand Dunes 30-second video, Darron Gedge's Geography Channel

Learning Check Point

Learning Check Point mjg8Please take a few minutes to think about what you just learned then answer the questions below to test your knowledge.

Barrier Islands

Barrier Islands azs2- How is a barrier island defined?

- What marine process is primarily responsible for the alignment of sand that is required to maintain a barrier island?

- How does the hydrodynamic regime affect barrier morphology?

Barrier islands are shore-parallel, elongated accumulations of sand that are constructed by waves and built vertically by the accumulation of sand from wind transport. They can be found along approximately 15% of the world’s existing coastlines, with the majority of them located along trailing edge or marginal sea coasts with wide, low gradient continental shelves. In some locations, they are isolated and separated from the mainland by either open bodies of water or marsh and tidal creek systems, depending upon the hydrodynamic regime of the area. However, in some locations, they can be attached to the mainland at one end (barrier spit) or both ends (welded barrier). The length of barrier islands can range from just a few kilometers to as much as 100 km, and they can be as wide as several kilometers wide.

Primary Morphological Components

The primary components of a barrier island system include the following:

- Nearshore, beach, and dune systems: these environments share the same characteristics as those that were discussed in the section on beaches.

- Backbarrier: the area located between the barrier and mainland and can consist of bodies of water such as bays, lagoons, and sounds, as well as marshes, tidal creeks, and tidal flats.

- Bays and Lagoons: shallow, open to partially restricted water areas located in the backbarrier.

- Marshes: salt-tolerant vegetated areas within the intertidal area of the backbarrier.

- Tidal Flats- flat, sandy to muddy areas that are exposed at mid to low tide along the backbarrier.

- Tidal creek: a backbarrier creek through which water flows during flood and ebb tide.

- Tidal Inlets: openings along a shore-parallel chain of barrier islands through which water is exchanged between the open ocean and the backbarrier environments during a tidal cycle.

- Tidal Deltas: sandy to silt-rich shoals that rise above the adjacent seafloor and are located on the landward and seaward side of tidal inlets.

Hydrodynamic Regime

Hydrodynamic Regime azs2Because barrier islands are built by waves, they do not develop in tide-dominated environments. Waves are responsible for the longshore transport of sediment, and it is this transport that drives the deposition of sediment to create elongated features consisting of sandy barrier islands. There are, however, numerous examples of barrier islands within mixed-energy as well as wave-dominated environments. In fact, the two fundamental types of barrier islands are recognized as wave-dominated and mixed-energy barriers.

Wave-Dominated Barriers

Wave-Dominated Barriers azs2Wave-dominated barrier islands are long, narrow barrier islands with typically widely spaced tidal inlets. Because of the wave dominance, the capability for longshore transport is high, and tidal inlets in this type of system are relatively narrow because longshore transported sediment acts to fill in the inlets and restrict their widths. The tidal deltas on the seaward side of the inlets, ebb-tidal deltas, also tend to be small compared to mixed energy barrier systems because waves tend to limit the distance that ebb-tidal deltas can migrate seaward.

Mixed-Energy Barriers

Mixed-Energy Barriers azs2Mixed-energy barrier island systems are typically short and wider at one end than the other end. Historically, this type of morphology has been referred to as a drumstick barrier island because of its approximate similarity in shape to the drumstick of a chicken leg. The tidal inlets between these barriers are large because of the relatively higher tidal energy. Compared to wave-dominated barriers, they also have large ebb-tidal deltas because the strength of the tidal currents is able to transport sediment seaward in a regime of relatively low wave energy. The relatively wider end of the island is the result of the accretion of sediment as waves refract around the edge of the ebb-tidal delta, causing a localized reversal in the longshore transport pattern and leading to sand accumulation.

Future of Barrier Islands

Future of Barrier Islands azs2In recent years, there have been numerous studies investigating how barrier island systems respond to change in sea level and impacts created by storms as they erode sediment and destroy coastal property. Because barrier islands form a true barrier along many inhabited coastal zones, they represent a line of defense for inland communities from the destructive power of storm surges and waves that are driven by large storms. Unfortunately, however, there are global trends in barrier size reduction because of reduced sediment input caused by damming rivers, human modifications to coastal systems, storm-driven erosion, and relative sea level rise.

In future modules, we will explore the dilemmas facing communities located on barrier islands and the question of whether these communities can expect to survive.

Check out these links to explore barrier islands further:

Louisiana's barrier islands: Barataria-Terrebonne National Estuary Program: Barrier Islands

Video and article on restoring Louisiana's barrier islands: Restoring Louisiana's Barrier Islands

Learning Check Point

Learning Check Point mjg8Please take a few minutes to think about what you just learned, then consider how you would answer the questions on the cards below. Click "Turn" to see the correct answer on the reverse side of each card.

Deltaic Coasts

Deltaic Coasts azs2- What is a delta?

- How does the morphology of a delta reflect the processes acting to shape it?

- Why are deltas at risk?

Geologic and archeological evidence clearly indicates that a significant part of the rise of modern societies and culture can be attributed to the development of the modern world's deltas, which started forming during the slowed post-ice age sea level rise. Numerous lines of evidence indicate that well-developed societies were occupying deltas in the time frame of 4,000 to 7,000 years before present because of the many natural resources that deltaic environments generally contain. Resources such as shellfish, fish, furs, and plants were necessarily taken from the wild by our ancestors, and so many ancient societies began proximal to deltaic environments.

The term delta comes from Herodotus, a Greek historian, and philosopher who recognized the similarity of the upside-down Greek letter delta (Δ) and the shape of the Nile river delta when viewed from the south toward the north.

What is a delta?

A delta is a subaerial and subaqueous volume of sediment that has accumulated at the mouth of a river as it enters into an open body of water. The largest deltas are the product of very large river systems that are transporting large quantities of sediment. The Ganges-Brahmaputra delta is one of the largest deltaic environments on the planet and carries vast amounts of sediment to the ocean. There, the sediment is reworked by strong tidal currents of the region to form inlets and sediment ridges.

Delta Morphologies and Driving Processes

Delta Morphologies and Driving Processes azs2Variations in delta morphology tell us something about the processes that cause and drive the evolution of deltaic environments. Globally, it is widely accepted that there are three end-member morphologies of deltas that reflect the relative influence of wave energy and tidal energy in the receiving basin or sediment input by the source river into the receiving basin. On a ternary plot, these three end members each represent one apex of the plot, and all deltas fall somewhere on this plot. Deltas that are primarily the result of high rates of sediment input tend to be elongated because of their rapid outbuilding associated with high rates of deposition into the receiving basin. Wave-influenced deltas have smooth, often arcuate shorelines with numerous ridges that reflect the longshore transport of river-delivered sediment by the high wave energy. Tidally influenced deltas have numerous shoreline perpendicular tidal passes and tributaries, with sediment bodies aligned parallel to the direction of tidal exchange.

Deltas in Crisis

Deltas in Crisis azs2During the last decade, a substantial amount of concern has arisen regarding the health of the planet's major deltas. Over-exploitation of deltaic resources by humans, the introduction of pollutants, and excess nutrients to the rivers, as well as the management of river water that feeds deltas has severely damaged the sensitive environments of many deltas. Additionally, reduced sediment loads in many deltas, because of the construction of dams, coupled with global sea level rise and/or local land subsidence has resulted in widespread loss of deltaic wetlands and fronting sandy barrier shorelines. Because deltaic plains are so heavily relied upon by humans and, in some cases, are densely inhabited by humans, there are, for some deltas, widespread efforts to try to halt coastal erosion and environmental damage.

For example, the wetlands of the Mississippi River delta have undergone substantial change during the last century, with large areas of wetlands converted to open water because of relative sea level rise and erosion by storms. The rate is just staggering, with a football field of wetlands vanishing into open water every 30 minutes! The loss of wetlands across the delta is so severe that communities and infrastructure that were once separated from the open Gulf of Mexico by wetlands are now exposed to open marine water and have become more vulnerable to the damaging effects of storm surge. As a result, the state of Louisiana has developed a series of plans to build new land and infrastructure that would help reduce the net loss of land. The staggering change between 1932 and 2011 can be seen in the two satellite images below.

More Information

- For more information on deltas, see Delta.

- For more information on issues with and plans to restore the Mississippi River Delta in Louisiana, see Restore the Mississippi River Delta.

Learning Check Point

Learning Check Point mjg8Please take a few minutes to think about what you just learned, then answer the questions below.

Estuaries

Estuaries azs2- What is an estuary?

- How do estuaries form?

- What sort of processes takes place in estuaries?

Definition and Morphology of Estuaries

Coastal geologists define an estuary as a semi-enclosed body of water with an open connection to the ocean and one or more rivers flowing into it. They represent a transitional environment between the solid mainland and the sea and because of the inflow of rivers are partially diluted with fresh water so that they do not contain normal salinity marine water. As a transitional environment, they are influenced by marine processes, such as waves and tides, as well as river processes, such as the delivery of sediment and fresh water.

The Importance of Estuaries

Some of the world's most productive ecosystems are located within estuaries and host a wide range of organisms. In fact, many species of commercially important fish and shellfish spend part of their life cycle within estuaries before reaching maturity. They are, however, an environment that, like many other coastal environments, faces a wide range of environmental problems arising from land-use practices, dumping of sewage and other pollutants, and the introduction of excess nutrients because of poor agricultural practices.

Historically, estuaries have been classified a number of ways, including how they formed and their morphology, the circulation patterns that are present within the estuary, and the relative importance of waves and tides within an estuary. In this module, we will only be discussing estuary formation and circulation patterns of classification.

Estuary Formation

Estuary Formation azs2Different ways that estuaries can form include:

- Ria Estuaries: rising sea level fills an existing river valley, such as what happened to create a special case of Ria known as the Coastal Plain Chesapeake Bay Estuary of the eastern U.S.A.

- Tectonic Estuaries: tectonic deformation of the Earth’s crust, such as faulting, creates a localized depression that fills in with marine waters such as San Francisco Bay. Water depths in tectonic estuaries can be highly variable.

- Bar Built Estuaries: migrating barrier islands or spits extend across the mouth of a bay and restrict the amount of marine water entering the bay to create an estuary. They tend to be relatively shallow and typically less than 10m of water.

- Fjord Estuaries: glacially carved, U-shaped valleys that filled with marine water since the end of the last ice age. They can extend long distances 10s to 100s of kilometers and as deep as several hundred meters.

Estuary Salinity Patterns

Estuary Salinity Patterns azs2The relatively higher density of saltwater compared to freshwater means that freshwater will float on top of saltwater. In some cases, there may be mixing between the two water masses but, in other cases, little to no mixing may take place to produce a highly stratified water column with a layer of buoyant freshwater situated above a layer of saltwater. The development of a well-mixed estuary or a highly stratified estuary is a function of the estuary morphology, magnitude of freshwater input, estuary-mouth tidal range, and how the tide propagates up the estuary. A classic comparison is that relatively shallow, bar-built estuaries are often well-mixed, and, alternatively, deep, fjord-style estuaries are highly stratified. It is also important to note that besides there being a vertical profile of salinity variation possible, there are also variations along the length of the estuary. Near the mouth of an estuary, one would expect to generally find the highest salinity water where the influence of the sea is the greatest and the most freshwater at the most inland extent where freshwater river systems enter into the estuary. These variations in salinity structures lead to differences in the distributions of salt-water and fresh-water tolerant plant and animal species within an estuary and how organisms use the estuary environments.

Recommended reading for salinity

- Harte Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies: Freshwater Inflows: An Estuarine System can be Classified by the Salinity Zone

Estuary Circulation Patterns

Estuary Circulation Patterns azs2Patterns of estuarine circulation play an important role in sedimentation within the estuary and the distribution of different ecosystems in the estuary. Fundamental control on the types of circulation patterns can be linked to the relative relationships of freshwater input, the tidal range, velocity, and direction of winds, and currents created by waves. Each of these is capable of creating currents within the estuary and thus control how freshwater and saltwater interact in the estuary and where sediment can accumulate within an estuary. For example, during periods of low river inflow to an estuary, wind-driven saltwater may move farther into an estuary than it would during high river discharge into the estuary. During intervals of high freshwater runoff, freshwater, and sediment may extend well into the estuary and lead to sedimentation near the mouth of the estuary in a location where sedimentation by rivers is typically low.

Earth Complexity in Action: Estuaries

Earth Complexity in Action: Estuaries azs2The complexity of natural systems and the complexity of the interaction between the various spheres of the Earth is extremely evident when considering coasts and coastal systems.

Consider the potential for the complexity of salinity and circulation within an estuarine system, a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water that has freshwater input by rivers and saltwater input by marine processes. The circulation of an estuary can vary substantially across a range of time scales such as daily, seasonally, or annually. Changes in freshwater input during periods of heavy rain, fluctuations in tides, or changes in the direction that the wind is blowing can all contribute toward how water moves around within the estuarine system. During periods of heavy rainfall, freshwater input may result in a much-lowered salinity in the estuary, whereas during periods of drought and strong onshore winds, salty water can be pushed into the estuary by waves and the salinity of the estuary increases. Complexity in an estuarine system exists because of the numerous interacting physical processes of the hydrosphere and atmosphere that act on the system.

Now, consider how this complexity may affect the anthrosphere or the part of the environment that is made or altered by humans for human activities or habitat. Suppose you were making a viable living, fishing oysters for commercial resale. Most oysters are relatively environmentally restricted, and too much freshwater can kill them, as can too much saltwater. Perhaps, one year, you are able to very successfully oyster fish an area of the estuary because the freshwater and saltwater input has been perfectly balanced to create optimal conditions for oysters very close to your home. The following year, there is so much freshwater runoff into the estuary that all of the oysters near to your home die or do not grow to the adequate size. As a result, you would have to travel to new locations in the estuary to find the optimal oyster growing conditions, something that might mean longer boat travel time for you and more fuel to get onsite, thereby reducing your net profit. So, the complexity of natural processes interacting with each other generates complexity for how society deals with these changes.

Summation

Summation azs2The complex interaction of estuary morphology, freshwater influx, waves, and tides leads to the diverse range of estuarine conditions and environments that exist on a global basis and that may exist daily to seasonally in an individual estuary. The high primary and secondary productivity of estuaries and the fact that they can provide an important buffer to inland communities and infrastructure against the open ocean make estuaries a critically important coastal system. Yet, many are at risk because of exploitation. The Chesapeake Bay estuary, for example, has experienced widespread degradation of fisheries because of damage to bay habitat from the introduction of excess nutrients and pollution, and extensive programs are underway to mitigate against the substantial damage that has already been done to the system.

For more information on estuaries, check out these links:

- Check out more information on estuaries.

- More details on human impacts are on this site: Hart Research institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies: Estuaries

- Watch a YouTube video about estuaries.

- Check out more information on the Chesapeake Bay.

Learning Check Point

Learning Check Point mjg8Please take a few minutes to think about what you just learned then answer the questions below.

Coastal Wetlands and Maritime Forests

Coastal Wetlands and Maritime Forests azs2- What is a coastal marsh?

- What are mangroves and what role do they play in capturing sediment and anchoring substrate?

- How can the presence of extensive marsh platforms and mangrove forests help to reduce inland storm surges and flooding?

Coastal wetlands and maritime forests are unique communities of vegetation that can exist along coastal zones. They are directly affected by coastal conditions including changes in water level due to tides, coastal river influx, freshwater, saltwater, wave activity, wind and salt spray, and storm surges. Inasmuch as they are communities uniquely synced to the conditions of their environment, even subtle changes in one condition can cause widespread deleterious changes to the plants themselves.

Coastal Wetlands

Coastal Wetlands azs2The term coastal wetlands defines an area of land that is permanently or seasonally inundated with fresh, brackish, or saline water and contains a range of plant species that are uniquely adapted to the degree of inundation, the type of water that is present, as well as the soil conditions.

In some cases, coastal wetlands can extend across extremely large areas, as is the case for southern Louisiana along the north-central Gulf of Mexico. The importance of coastal wetlands is well known in southern Louisiana because there, like many other places, the coastal wetlands provide important habitat for a wide range of organisms. They also protect inland communities from the large storm surges that tropical cyclones can produce, by creating friction against an incoming storm surge, resulting in a reduction of the magnitude and extent of inland flooding during tropical cyclones. The greater the width of intact wetlands, the less likely it is that more inland areas will experience the full force of a tropical cyclone. Southern Louisiana has been, however, experiencing drastic loss of wetland at rates that for the last several decades have been equivalent to the loss of a U.S. football field every approximately 30 minutes.

Coastal Wetland Examples

Coastal wetland is used broadly here to identify areas where wetland plants inhabit the coastal zone, in either freshwater or saltwater environments of the coastal zone. For this reason, along the continental U.S. coastal zones, it includes vegetated environments such as salt marshes, fresh marshes, bottomland hardwood swamps, and mangrove swamps. In the United States, coastal wetlands extend across nearly 40 million acres and constitute approximately 38% of the total wetlands in the conterminous U.S.

- Marsh: A marsh is a type of wetland that consists of herbaceous plants (plants with leaves and stems). Typically, there is a period of annual dieback or at least a resting period from growth, and the system can be either salt or freshwater in nature.

- Salt Marsh: True salt marsh is strongly affected by the tides of a given area on a daily basis because they are located within the intertidal window of elevation. Along the coast of the U.S., all salt marsh experiences a severe to slight dieback during the winter, but begins growing strongly the following year with the return of warmer temperatures. Typical salt marsh structure includes tidal creeks through the marsh platform and localized ponds that may hold some water even during very low tides.

- Fresh Water Marsh: On a global basis, the distribution of coastal-zone freshwater marsh is most closely tied to river systems that enter into coastal zones. The steady influx of freshwater into coastal rivers provides an opportunity for fresh-water vegetation to dominate and prevents the incursion of flora that requires some level of salinity. The Florida Everglades of Florida in the U.S. represent some of the largest, and perhaps the largest, freshwater marsh in the world.

- Swamp: Forested wetlands with little circulation to nearly stagnant conditions are characteristic of swamps. Freshwater, brackish, and saline water are all possible environmental conditions in a swamp.

- Bottomland Hardwood swamps: In the coastal zone, bottomland hardwood forests are closely linked to the availability of freshwater. As a result, most extensive bottomland hardwood swamps are in low-lying river flood plains. Occasional flooding of these environments provides sediment to help anchor the vegetation and nutrients that are critical to growth. Excessive flooding or the introduction of saline waters can have serious effects on the health of such systems.

- Mangrove Swamps and Forests: Mangrove swamps are distributed through tropical and subtropical regions. There are numerous species of mangroves, but they all represent a plant that is halophytic or salt-loving and is associated with other trees and plants that grow within brackish to saline tidal waters. They may consist of a very complicated maze of woody roots and limbs. Depending upon the species of mangrove, very complicated interwoven root structures can develop and provide a significant buffer against erosion and inland progressing waves and storm surges during high-energy events. Across the U.S., they are restricted to low-latitude environments because of the species' intolerance for cold temperatures. Three different species exist from south Florida along to the Texas Gulf Coast, and, in fact, one of the largest mangrove swamps in the world is on Florida's southwest coast where Red Mangrove form structurally resilient coastal environments because of their interlocking woody growth patterns.

Maritime Forests

Maritime Forests azs2Maritime forests are coastally located areas of woods that develop on elevations and topography that is higher than that of coastal wetlands. They primarily rely upon shallow freshwater and cannot tolerate long exposure to salty water; even salt spray can be detrimental to some species of trees that establish maritime forests habitats. Such systems are discontinuously distributed along the U.S. Atlantic coast, but can be found elsewhere as well. In most cases, the soil composition promoting the growth of these forests is sand, either derived from sedimentary units deposited in the past or more recent deposits, such as beach ridges.

Coastal Wetlands and Maritime Forests Summary

Coastal Wetlands and Maritime Forests Summary azs2Coastal wetland and maritime forests represent unique provinces of vegetation that are uniquely adapted to the harsh conditions of the coastal zone. They provide a range of different habitats for coastal animals and simultaneously provide an important coastal barrier to more inland-located environments, as well as people and infrastructure. There is, however, much concern for the future of our modern coastal vegetation as the different provinces of coastal vegetation face continued exposure to pollution and excess nutrient inputs, changes in the elevation of sea level, and repeat large-scale storm impacts.

For more information on coastal vegetation, check out these links:

- Very good overview of salt marshes

- Nice YouTube video about freshwater marshes

- Information on freshwater marshes

- More information on maritime forest

Learning Check Point

Learning Check Point mjg8Please take a few minutes to think about what you just learned and then answer the questions below.

Module 3 Lab

Module 3 Lab mjg8Introduction

In this lab, you will examine a sandy shoreline's dynamics. Two types of data will be explored: shoreline erosion using Google Earth timeline and shoreline elevation change data produced from elevation profiles. These two types of data yield a great deal of information about the dynamics of a sandy, wave-dominated shoreline and reveal trends in the erosion and deposition of sediment.

Important!

We advise you to either print or download/save this document as it contains the steps to complete the Module 3 Lab in Google Earth. In addition, it includes prompts for measurements and questions that you should take note of (by writing them down or typing them in) as you work through the lab.

Download

Statement of Use of AI on Exams, Quizzes, and Labs

Statement of Use of AI on Exams, Quizzes, and Labs

Instructions

Once you have worked through all of the steps in the worksheet, you will go to the Module 3 Lab (Quiz) to complete the Lab by answering multiple-choice questions. The answers to questions on this Lab worksheet will match the choices in the multiple-choice questions in Canvas. Submit the quiz in Canvas for credit.

Summary and Final Tasks

Summary and Final Tasks sxr133Throughout this module, you were introduced to a wide range of coastal environments that exist across Earth. Each of these has a unique geomorphology that results from the interplay and influence of processes such as waves and tides, sediment supply, climate, type of bedrock, and, of course, plate tectonics.

A focus of the module was to point out that processes such as plate tectonics (Module 2) may affect the characteristics of a coast at the scale of several 100s to 1000s of kilometers along a continental margin but along such an extent of coast there may be smaller scale (10s to 100s of kilometers) coastal systems that are considerably different from one another. For example, the trailing-edge coast of eastern North America varies substantially from Canada to Florida, with rocky coastline characteristics in northeastern Canada and the northeastern U.S. to major sand-rich barrier island systems farther south around the mid-Atlantic states (e.g., Cape Hatteras of North Carolina) of the United States. These variations along a continental margin are a result of variability in sediment supply, climate, and hydrodynamic regime along the length of the eastern North America continental margin. The same type of along-margin variability in processes holds true along other continental margins, and it is clear that a unique suite of processes collectively contributes to create the wide range of global coastal geomorphologies that are evident on Earth today.

You have reached the end of Module 3! Double-check the Module 3 Roadmap (in Goals and Objectives) to make sure you have completed all of the activities listed there before you begin Module 4.

References and Further Reading

- Coastal Landforms and Processes

- Text Book on Coasts: Davis, R.A. and FitzGerald, D.M., 2004, Beaches and Coasts, Blackwell Science, Oxford, England. 419 p.

- Barrier Island Morphology: Schwartz, L.M., 1971, The multiple causality of barrier islands, Journal of Geol., v. 79, no. 1, p. 91-94.

- Danube Delta Discussion

- Nearshore Dynamics

- The Not-So-Mysterious Loss of Salt Marshes and Ecosystem Services